The important thing is not to stop questioning… Never lose holy curiosity – Albert Einstein

One of the tenets of my own musical study, my writing, and my life in general is to “stay curious”. I’ve always been curious and from a young age, I wanted to know stuff – from dinosaurs to Egyptology, Old English to the piano music of Schubert, or setting up my own website/blog and learning basic computer coding. Today, the internet is a remarkable resource for the curious-minded and my usual habit, if I want to find out something, is to look it up on Google or YouTube.

© DALL-E2

Curiosity is essential for the musician. Not only does it drive exploration, keep practice interesting, improve problem-solving skills and creativity, and help to maintain self-motivation, it also fosters creativity, thus encouraging one to explore further – new repertoire, techniques and more to improve one’s skills and expand one’s musical horizons.

Mindless, uncurious practising is boring. It’s often simply “going through the motions”, without thinking creatively about what you are doing at the piano. Look closely at the score, ask it questions – why has the composer used that harmony/ combination of notes/specific articulation? – and seek your own answers (and remember that there isn’t necessarily a single or straightforward answer, nor that there is a “right answer” or “right way” of doing things – adopting this mindset is liberating in itself and breeds even more curiosity and creativity).

The curious pianist approaches each practice session with an open mind – “what can I do today that’s different/better?“. Curiosity helps to keep practice engaging and interesting (because let’s be honest, practicing can be tedious, especially if you’ve been working on the same piece or pieces for long periods of time, for example, when preparing for an exam or diploma performance). By approaching practice with a sense of curiosity, you can make the process more enjoyable and satisfying – and, importantly, more motivating.

J.S. Bach: Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd!, BWV 208, “Hunt Cantata”: Aria: Schafe können sicher weiden (Sheep May Safely Graze) (arr. A. Ffrench for piano) (Alexis Ffrench, piano)

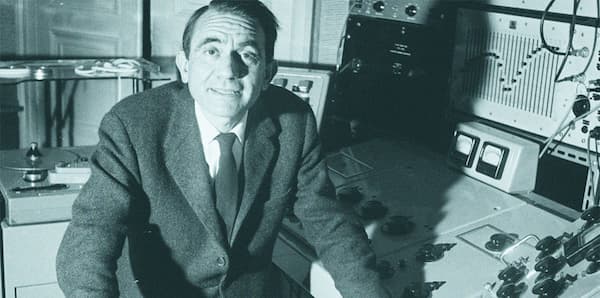

© librarymusicsource.com

Curiosity improves problem-solving skills too. When you encounter a difficult passage in a piece or a technical problem in your playing, curiosity can help you to find creative solutions. It encourages you to think outside the box and come up with new ways to approach a problem.

A good teacher will encourage curiosity in their students and give them the tools to be curious in their own practicing and musical study (and curiosity is related to independent learning and self-teaching which will be covered in a separate post). Curious students tend to be more eager to learn – and to learn more – motivated and self-starting.

Away from the practice room, be curious about your encounters with other music. Go to concerts, experience music with which you may or may not be familiar. Listen with an open mind and find inspiration from others’ music-making.

Curiosity allows us all, at whatever level we play, whether amateur or professional, to push ourselves to improve and expand our skills, which is essential to becoming a better musician.

Karol Szymanowski: Król Roger (King Roger), Op. 46: Chant de Roxane (arr. P. Kochanski for violin and piano) (Luka Faulisi, violin; Itamar Golan, piano)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter