In 1935, the filmmaker Josef von Sternberg directed a romance film starring actress Marlene Dietrich. Titled “The Devil is a Woman,” it was the last of the six Sternberg-Dietrich collaborations for Paramount Pictures. The plot is based on a novel by Pierre Louÿs, and the action is set during Carnival in early 20th century Spain. The provocative title of this classic film resurfaced in 2004 in a play by the Australian writer, playwright, and librettist Mark Doyle, who is better known as Louis Nowra. His “The Devil is a Woman” does not take us to Spain but into the realm of the infamous “Witch of Kings Cross.” His play is based on Rosaleen Norton and her mystic relationship with the disgraced Sydney Symphony Orchestra conductor Sir Eugene Aynsley Goossens (1893-1962). Goossens had spent nine years in Australia and, besides conducting the Sydney Symphony, was director of the NSW State Conservatory of Music. He was forced to resign after a major public scandal in 1956, only a year after being knighted.

Eugene Goossens: Phantasy Concerto, Op. 60 (Howard Shelley, piano; Melbourne Symphony Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

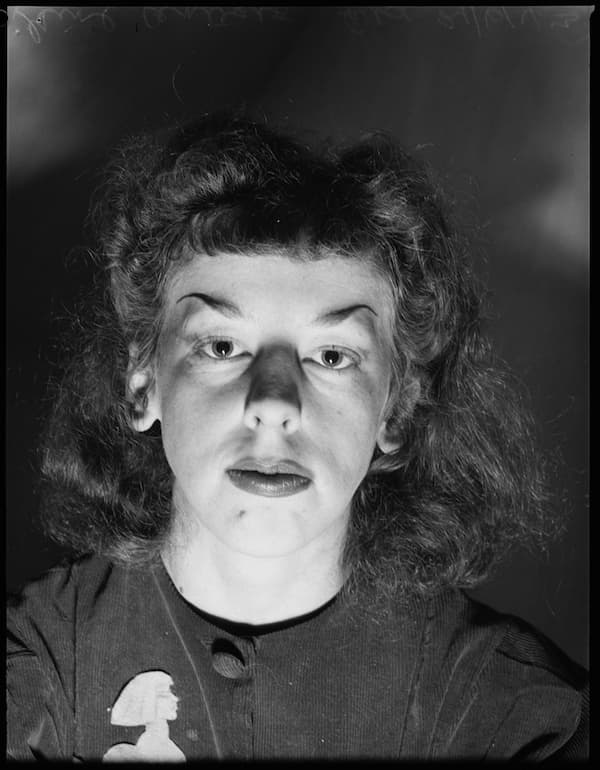

Rosaleen Norton, 1943

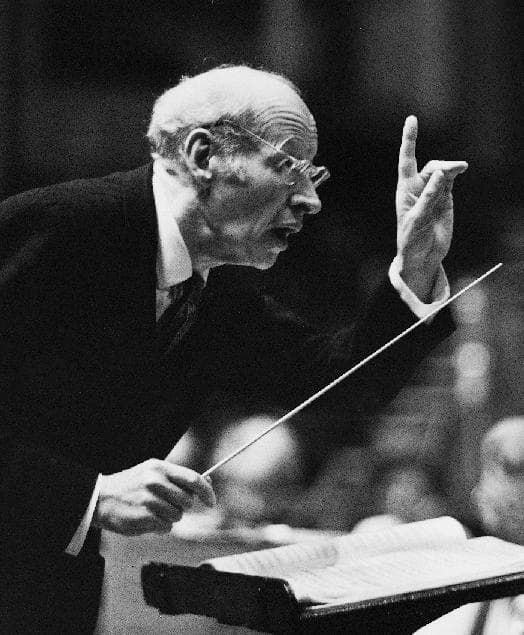

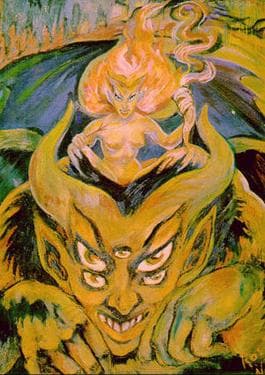

The “Devil Woman” in question was Rosaleen Miriam Norton (1917-1979), a New Zealand-born Australian artist and occultist. Known as “Thorn,” she essentially practised witchcraft devoted to the Greek god Pan. “Her paintings often depicted images of supernatural entities such as pagan gods and demons, sometimes involved in sexual acts.” Apparently, her “beliefs and cosmology reflect her unique approach to the magical universe as it was inspired by the night side of magic.” As Norton lived and led her own coven of Witches in the bohemian area of Kings Cross, Sydney, she soon acquired the nickname “Witch of Kings Cross.” The Australian government, as you might well imagine, wasn’t particularly thrilled and harshly censored her works and attempted to “prosecute her for public obscenity on a number of occasions.” Meanwhile Goossens had started his career in England as an acclaimed violinist before becoming assistant conductor to Thomas Beecham. He decided to become a full-time conductor and founded his own orchestra. He even gave the “British concert premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring on 7 June 1921 at the Queen’s Hall with the composer present.” Subsequently, he accepted positions at various U.S. orchestras, and between 1931 and 1946, he succeeded Fritz Reiner as the conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Goossens turned down the musical directorship of the Covent Garden Royal Opera and Ballet Company and instead took on the appointment in Sydney. “He raised the orchestra to international repute, discovered the soprano Joan Sutherland and was the first to suggest the building of the Sydney Opera House on Bennelong Point. In 1955 he was knighted for his services to Australian music.” On his arrival in Australia, “he earned more than the prime minister,” but rumours soon started to circulate that he had an unusual interest in the occult.

Eugene Goossens: Concertino for String Octet, Op. 47 (Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Chamber Ensemble)

Sir Eugene Goossens, 1961

Apparently, Goossens read a copy of “The Art of Rosaleen Norton,” Intrigued he decided to write her personally, and she invited him to meet up. They instantly became friends and, soon thereafter, lovers. They exchanged a great number of passionate letters, and although Goossens did ask Norton to destroy them all, she kept some hidden away. Things might have been kept out of the public’s eye, but a woman made an official police report in 1955 saying, “her life had fallen apart after taking part in a Satanic Black Mass run by Rosaleen Norton.” Whether true or not, the newspapers were all over the story, and after a public outcry, the police started to investigate her supporters. They raided Norton’s home and found plenty of incriminating materials, including the Goossens letters. Goossens was in Europe at the time, and he was unaware that the Sydney police had conducted the raid on her flat. He returned to Australia in March 1956 and was detained at Sydney Airport. When they searched his bags, they found photographs, prints, books, a spool of film, some rubber masks and sticks of incense. Although not immediately arrested or charged, Goossens agreed to a police interview several days later.

Eugene Goossens: Romance, Op. 57 (Robert Gibbs, violin; Gusztav Fenyo, piano)

Rosaleen Norton’s The Seance

When he was confronted with various photographs of Norton’s ceremonies and his letters, he was forced to plead guilty for “bringing blasphemous, indecent or obscene works” into the country and was fined £100. He paid the fine, but his reputation was ruined. He resigned his positions at both the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and New South Wales Conservatorium of Music and returned to Britain, his international career ending in disgrace. It also ended his marriage, and his wife sought refuge in a French convent.

The scandal inspired a novel by Inez Baranay, the opera Eugene & Roie by Drew Crawford, an extended documentary entitled “The Fall of the House,” and the Nowra play “The Devil is a Woman.” The saga continues as the anonymous owner of Goossens’ private letters is threatening Nowra with legal action. It is of yet unclear who instigated the lawsuit, but Goossens’s daughter Renee “is saddened and disappointed that the affair continues to overshadow her father’s achievements.” The playwright quoted only from one letter used in the original police evidence, and he is aware of the embarrassment factor surrounding the story. “Here is a poverty-stricken witch from Kings Cross and an upper class, stiff upper lip Pom writing about the sex they would have while worshipping Pan.” Occult practices, after all, might have been the source of Goossens’ creativity and artistic imagination.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Eugene Goossens: Oboe Concerto, Op. 45 (Albrecht Mayer, oboe; Bamberg Symphony Orchestra; Jakub Hrůša, cond.)