Credit: http://nasher.duke.edu/

When Cage conceived it, in the years immediately after the Second World War, he was attempting to remove both composer and artists from the process of creation. Instead, by asking the musicians specifically not to play, Cage allows us, the listeners, to create our own music, entirely randomly and uniquely, by listening to the noises around us during four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence and removing any pre-conceptions or pre-learned ideas we may have about what music is and how it should be presented and perceived. The work is an example of “automaticism”, and was, in part, Cage’s reaction to a seemingly inescapable soundtrack of “muzak”.

Neither composer nor artists have any control over or impact on the piece; the piece is created purely from the ambient sounds heard and created by the audience. In this way, the audience becomes crucial: this aural “blank canvas” reflects the ever-changing ambient sounds surrounding each performance, which emanate from the players, the audience and the building itself.

On another level, Cage was challenging – and exploiting – the conventions of modern concert hall etiquette. By programming the work to be performed at a prestigious venue, with high-status players and conductor, the audience’s expectations are heightened long before the performance begins. No wonder the audience felt “cheated” the first time they heard it, and the piece remains controversial to this day.

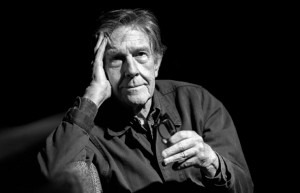

John Cage

Credit: http://home.utah.edu/

“They missed the point. There’s no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence, because they didn’t know how to listen, was full of accidental sounds. You could hear the wind stirring outside during the first movement. During the second, raindrops began pattering the roof, and during the third the people themselves made all kinds of interesting sounds as they talked or walked out.”

John Cage, speaking about the premiere of 4’33”

I’ve never been to a live performance of Cage’s 4’33” and I would to fully experience it, to sit and listen to the sounds of the concert hall – all the murmurations, breathing, whispering, programme-rustling, snuffling, air-conditioning humming, street sounds from outside (sirens, tube trains rumbling). And also to have the opportunity to “imagine the sound” in one’s own head.

Silence is very important in music. Why else do we have rest markings and fermatas (pauses) to demand silence from the performer? Composers use silence to create drama, suspense, anticipation, to allow us to savour a particularly delicious or sumptuous phrase, a really rich harmonic sequence, or cadence, and to prepare us for, or surprise us with new material. Composers such as Messiaen and Takemitsu employ carefully-nuanced silences to create atmosphere, and to allow the listener (and performer) time for repose or contemplation. And think about the two minutes of silence we observe on Armistice Day and during the Cenotaph ceremony on Remembrance Sunday. While people fall silent in remembrance, we hear sounds around us more acutely. In 4’33” Cage is asking us to focus on the sounds around us, to listen to background noise, rather than blanking it out.

John Cage’s 4’33” is important not just in the history of modern music, or the concept of artistic “creation” and our notions of what constitutes “music”, but because it forces us to listen to silence, to take time out to listen, and really listen. It is also the best example, in my mind, of audience participation: it is music which invites us to “join in”, take part, and make our own unique contribution to the whole experience.

4’33” is well-enough known in American and European concert halls that there is very little of the discomfort the piece can engender. Most audiences sit there passively and wait until it’s over. I’ve performed this piece many times. My favorite time was in a cabaret in St Petersburg, Russia. I would venture to say that no one knew what to expect and the energy and tension in the room was a nice experience. The bubble “popped” when someone’s cell phone rang to the tune of “Light Cavalry Overture.” But for me the piece is less about the aural surroundings than it is about our conception of the passing of time (another of Cage’s interests). Sometimes the piece flies by, other times it seems agonizingly slow. You look at your stopwatch and can’t believe only 2 minutes have passed – it seemed like an eternity. That’s really what Cage was trying to get at, whether he knew it or not.

To the interlude.hk admin, Thanks for the well-presented post!