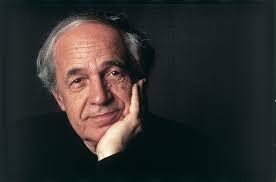

Pierre Boulez (1925-2016) was never particularly interested in making friends! Rather, he became thoroughly absorbed in a mission to write music worthy of his time, and to fight cynicism and indifference wherever he found them. That he mercilessly dismantled the monuments of classical music did not necessarily increase his mass appeal. Always outspoken and extremely articulate, Boulez issued a stern warning to composers. “What a delight it would be for once to discover a work without knowing anything about it. Shall we ever make up our minds to disregard contexts and to forget the time factors so relentlessly insisted upon by the history books.” Boulez was not disturbed by the variety inherent in the stylistic pluralism of the 20th century, only by the seeming “lack of real adventure in rediscovering the past but without its inherited meanings.”

Pierre Boulez (1925-2016) was never particularly interested in making friends! Rather, he became thoroughly absorbed in a mission to write music worthy of his time, and to fight cynicism and indifference wherever he found them. That he mercilessly dismantled the monuments of classical music did not necessarily increase his mass appeal. Always outspoken and extremely articulate, Boulez issued a stern warning to composers. “What a delight it would be for once to discover a work without knowing anything about it. Shall we ever make up our minds to disregard contexts and to forget the time factors so relentlessly insisted upon by the history books.” Boulez was not disturbed by the variety inherent in the stylistic pluralism of the 20th century, only by the seeming “lack of real adventure in rediscovering the past but without its inherited meanings.”

Taking harmony lessons with Olivier Messiaen in 1944 decisively shaped Boulez’s musical vision. For one, Messiaen introduced his students to medieval music and the music of Asia and Africa. Yet, Boulez also knew that he had to further explore the 12-tone method introduced by Schoenberg a generation before. “I had to learn about that music, to find out how it was made. It was a revelation—a music of our time, a language with unlimited possibilities. No other language was possible. It was the most radical revolution since Monteverdi. Suddenly, all our familiar notions were abolished. Music moved out of the world of Newton and into the world of Einstein.” In 1951, Boulez stormed onto the scene with his provocative article “Schoenberg is dead,” in which he accused the older composer of not having pursued the serial system to its logical conclusion by excluding rhythm and form. Boulez’s answer emerged in his earliest uncontested masterpiece, Le Marteau Sans Maître for voice and ensemble, a work Stravinsky described as “one of the few significant works of the postwar period of exploration.”

The stage was set for the development of a compositional style that is non-repetitive and uses anti-tonal intervals and contrapuntal construction. The characteristic Boulez sound remains essentially unemotional on the surface but is infused with brilliant color and rhythmic discipline. Much of this sound it not only the result of his reactionary aesthetic, but also the product of his famously acute ears. It was said that Boulez could not only hear a pin drop, he could also tell you the key! Boulez took up conducting as a way of introducing the public to the masterpieces of the first half of the 20th century. Without that knowledge, Boulez argued, audiences would find the music of their own time incomprehensible. His broad conducting activities brought him to Bayreuth, London and even New York City, and he received a total of 26 Grammy Awards during his career. Relentlessly searching and questioning, Boulez turned to the concept of the work in progress in his own compositions. Inspired by the novels of James Joyce, the final measures of these works are always in view, without ever being reached or achieved.

Boulez, who spent much of his life in self-imposed German exile, was looking to completely reorganize the French music scene. For one, he advocated burning down all opera houses. On a more practical yet hardly less controversial level, he started an ambitious project to create “a musical center in which experimentation can take place on a permanent basis.” The result was the “Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique,” abbreviated IRCAM.” A dedicated 31-piece orchestra, the “Ensemble Intercontemprain,” supported significant research into acoustics, instrumental designs and into the process of composition itself. Incorporating American computer music expertise and related technologies brought musicians and scientists into close contact, predictably not always in the most harmonious way. Boulez never composed an opera, but he determinedly tried to facilitate a meaningful dialogue between the music of the present and the music of the past. Relying on audacity, innovation and creativity, Boulez “changed how we listen to the music of our time.”

Pierre Boulez: Dérive 2

More Inspiration

-

Henry David Thoreau: Walden Discover how Henry David Thoreau's Walden inspired classical composers

Henry David Thoreau: Walden Discover how Henry David Thoreau's Walden inspired classical composers - Whispers of Love and Loss

Schumann’s Liederkreis, Op. 24 (Part 2) How Heine's romantic irony and Schumann's musical sensitivity create this masterwork - Whispers of Love and Loss

Schumann’s Liederkreis, Op. 24 (Part 1) We analyze the love, loss, and romantic irony in German Lied tradition -

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms