The Musicians, Caravaggio

Robert de Visée

Suite in E Minor for Two Theorbos

Paired with the paintings were examples of the different instruments themselves, selected from the museum’s vast collection of historical instruments, popular during the Baroque period: a beautifully decorated lute attributed to Wendelin Tieffenbrucker (active in Padua, 1570-1590), a large theorbo (belonging to the lute family), two flageolets (members of the flute/recorder family) and a magnificent violin by the great Cremona violin maker Nicolo Amati (1596-1684).

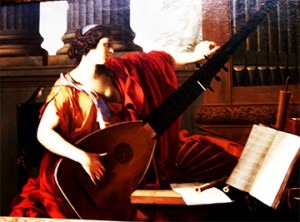

Allegory of Music, Laurent de la Hyre

J.S.Bach

Lute Suite in E Minor, BWV 996

The two other paintings in the gallery also establish a relationship between period instruments and their respective protagonists. The painting ‘Allegory of Music’ shows a classical female figure tuning a large theorbo in front of a classical background with a multitude of other various Baroque instruments next to her, an open book of sheet music, another lute, a violin with a broken string, flageolets, and an organ, beautifully decorated with oak leaves. The ‘Lute Player’ shows an attractive, elaborately dressed young man with a plumed hat, strumming a lute seemingly absentmindedly, a distant look in his eyes, his mouth slightly ajar, as if singing a love song to an absent lover. Behind him are a series of open music volumes of lute tablature, indicating (just as in modern guitar tabs) the fingering of notes rather than the pitches.

The two other paintings in the gallery also establish a relationship between period instruments and their respective protagonists. The painting ‘Allegory of Music’ shows a classical female figure tuning a large theorbo in front of a classical background with a multitude of other various Baroque instruments next to her, an open book of sheet music, another lute, a violin with a broken string, flageolets, and an organ, beautifully decorated with oak leaves. The ‘Lute Player’ shows an attractive, elaborately dressed young man with a plumed hat, strumming a lute seemingly absentmindedly, a distant look in his eyes, his mouth slightly ajar, as if singing a love song to an absent lover. Behind him are a series of open music volumes of lute tablature, indicating (just as in modern guitar tabs) the fingering of notes rather than the pitches. The exhibition raises the question “What did people ‘hear’ when they looked at these paintings of musical performances?” Music of that Baroque period was very much part of everyday life and not just seen as entertainment. It touched all levels of society — the church, the courts, the aristocratic salons and, through the popularity of opera, the working classes.

The exhibition raises the question “What did people ‘hear’ when they looked at these paintings of musical performances?” Music of that Baroque period was very much part of everyday life and not just seen as entertainment. It touched all levels of society — the church, the courts, the aristocratic salons and, through the popularity of opera, the working classes. Handel

Ariodante, HWV 33, Act II: Scherza infida

Church music — at this time of the Counter-Reformation — saw a tremendous change with the organ becoming a focal point in church services, made possible with the development of great instruments, such as the great Silbermann organs, and through the great oratorios and musical compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Händel. Music during Mass was no longer just relegated to chants by monks, but now included active participation of the congregation.

The courts of Europe, the aristocratic salons and the emerging financial, commercial and professional classes created their own musical experience. The proliferation of instrumental music in chamber settings was aided by the magnificent creations of violin makers, such as Stradivarius, Guarneri, Amati and lute makers such as Tieffenbrucker. The instruments, as well as viola da gambas and harpsichords — all refined instruments of the Baroque era — inspired Baroque compositions of great virtuosic and expressive skill. These new instruments and their individual colors also inspired new instrumental forms: dances (allemande, gavotte, gigue), variations, counter-point and alternation between solo and tutti passages — magnificently illustrated by the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach, Georg Friedrich Händel and Antonio Vivaldi.

The courts of Europe, the aristocratic salons and the emerging financial, commercial and professional classes created their own musical experience. The proliferation of instrumental music in chamber settings was aided by the magnificent creations of violin makers, such as Stradivarius, Guarneri, Amati and lute makers such as Tieffenbrucker. The instruments, as well as viola da gambas and harpsichords — all refined instruments of the Baroque era — inspired Baroque compositions of great virtuosic and expressive skill. These new instruments and their individual colors also inspired new instrumental forms: dances (allemande, gavotte, gigue), variations, counter-point and alternation between solo and tutti passages — magnificently illustrated by the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach, Georg Friedrich Händel and Antonio Vivaldi. The human voice, considered the oldest and most ‘natural’ of musical instruments, also found a new expression in the ‘Baroque’ voices of Castrati singers, whose interpretations accentuated differences in tone color between lower and higher registers — most valued when emphasizing agility, purity and clarity, stirring “the passions of the soul”.

Many paintings of the period, including many by the Dutch masters Rembrandt and Vermeer, open the possibility of an enhanced viewers’ contemplation – not only in sight but also in sound.

Yes, I love this place