During the mid-1920s, Béla Bartók experienced a compositional fork in the road. His violin sonatas had represented him as a musician on the international stage, while the “Dance Suite” was a national composition celebrating the 50th anniversary of the unification of Buda and Pest to form the Hungarian capital. Haunted by highly critical reviews that he was “un-Hungarian,” Bartók composed nothing between December 1924 and the summer of 1926. An additional reason for this compositional silence was his attempt to continue building his career as a pianist. As he wrote, “it is imperative to give concerts or do anything else which brings in money.”

Béla Bartók in January, 1928

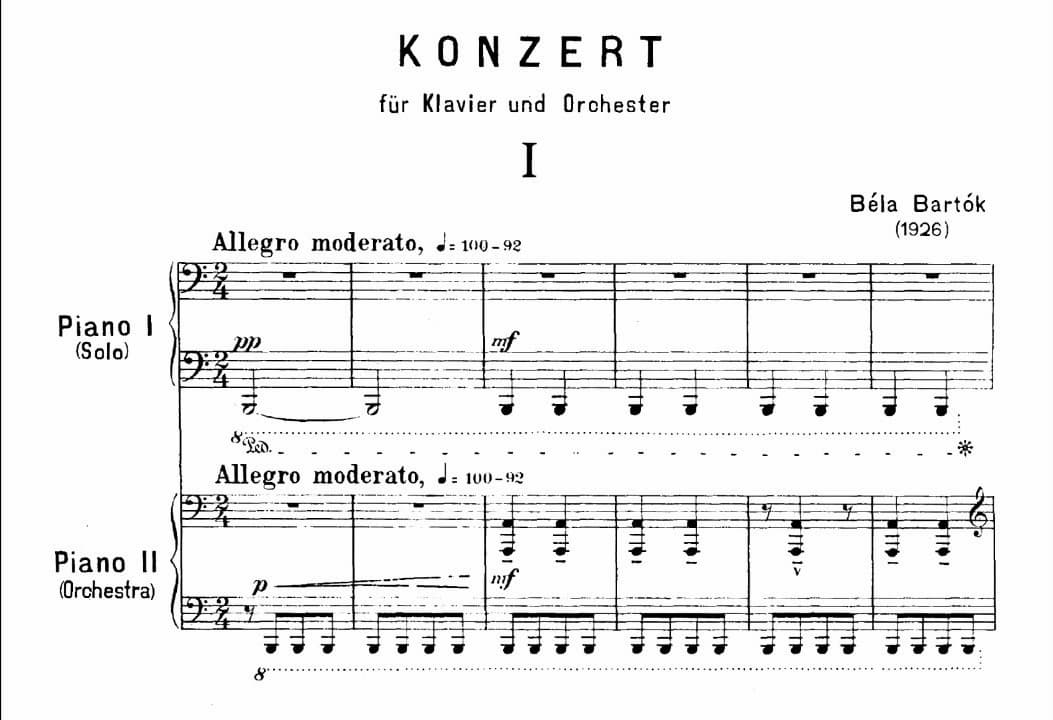

As a composer-pianist, Bartók quickly came to the conclusion that he needed to write a repertory for himself. He often included works by the new Hungarian school in his recitals, and much of the piano music he had composed between 1908 and 1918 was showing its age. As such, he declared, “a concerto must be my next work.” True to his word, he worked on a piano concerto between August and November 1926 and premiered the work at the fifth International Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music in Frankfurt on 1 July 1927. Bartók featured as the soloist and Wilhelm Furtwängler conducted.

Béla Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 1, “Allegro moderato” (Nelson Freire, piano; Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Gielen, cond.)

Bartók referred to the year 1926 as a turning point in his oeuvre. “I believe,” he wrote, “that I have consequently developed into a certain direction, at least from 1926 onwards when my works started to become a lot more contrapuntal, and more simple on the whole. This period is also characterized by that powerful emphasis on tonality.” The primary musical influences on Bartók’s compositional language at his time are Baroque techniques and the works of Igor Stravinsky. As such, the First Piano Concerto is the summation of all those tendencies in a fascinatingly rough and percussive style. In fact, critical reaction was unanimously outraged, but for the composer, there was no turning back from the new style.

Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 1

To be sure, with its emphasis on the rhythmical element, this concerto radiates tremendous energy, and “the rather curt thematic material appears to be almost in contrast to the rhythmical-metrical and to the contrapuntal complexity.” Bartók described the work as “being scored in E minor,” and the themes are based on a single motivic core presented in the introduction to the opening movement. As a scholar writes, “Above beating tone repetitions, a primordial motif unfolds first powerfully rhythmical in the horn, and then like a ritual motive in the bassoon…The entire character of the concerto is presented in ostinato technique, motific repetition, and a performance style indicated as “con durezza” (with hardness).

Béla Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 1, “Andante” (György Sándor, piano; Hungarian State Orchestra; Ádám Fischer, cond.)

Here as elsewhere, Bartók treats the piano as a percussive instrument. The outer movements are heavy with ostinatos, with reiterations, “with complex chords that make a noise effect and with scales thickly doubled in thirds in the bass. The central Andante makes the new kinship of the instrument explicit, for the piano is at first accompanied only by timpani, drums, and cymbals in a mood of quiet nocturnal signaling.” As a scholar explains, “absent altogether from the slow movement, the strings are used in the others predominantly as a chordal mass, with melodic lines taken mainly by the wind.” Bartók performed his First Concerto in October 1927 in London, Prague, and Warsaw, with a November performance conducted by Anton Webern.

We need to remember that Bartók’s First Piano Concerto is not a youthful composition, but a work of his maturity composed when he was forty-five years old. When it first sounded in the United States in 1928 a reviewer wrote, “There were broken bits of themes hammered out on the piano and answered by equally angry blasts of wind instruments. The only sustained motive is that of bitterness, and the sum total is unmitigated ugliness.” As Bartók later recalled, “I wrote my first piano concerto in 1926. Its structure has turned out a little, you might even say, very difficult for both the orchestra and the audience. That is the reason why some years later I intended to write my Second Piano Concerto as a counterpoint to the first.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter