Nell Shaw Cohen: The Course of Empire

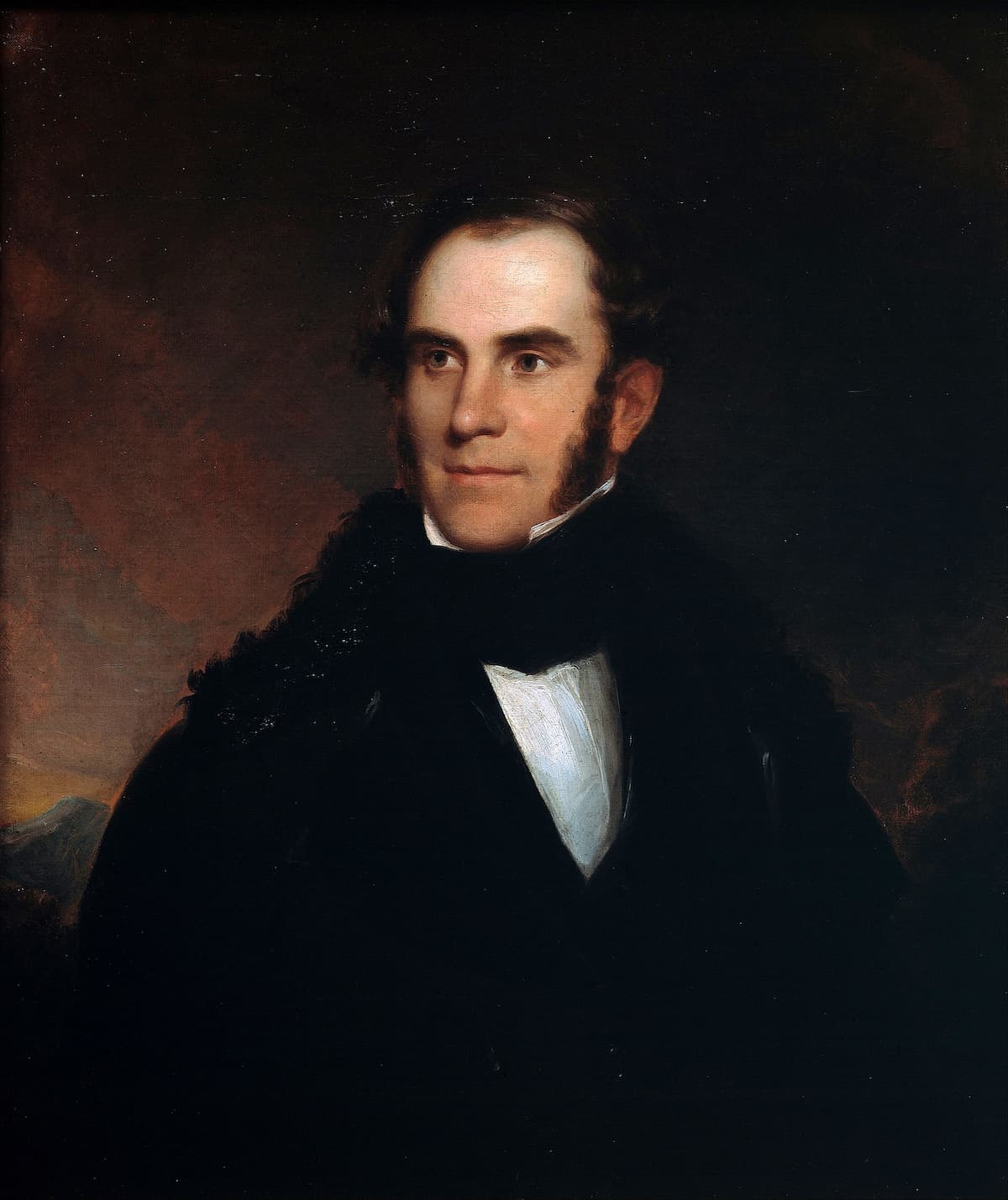

The English-born American artist Thomas Cole (1801–1848) was the first significant American landscape painter and was the founder of the Hudson River School in New York in the mid-19th century.

Asher B. Durand: Thomas Cole, 1837

Although his highly romantic pictures of the unspoiled Hudson River valley were the mainstay of his career, he also produced allegorical works, the most famous of which is The Course of Empire, which shows the same landscape, pinned to a repeating mountain. Over the centuries, the land changes from one of natural beauty (The Savage State), through The Arcadian or Pastoral State, The Consummation of Empire, Destruction, and Desolation. It is thought that Cole had a larger point he was trying to make: in setting aside nature or overriding it, we set the path of our own destruction.

In his advertisements for the series, Cole quoted Lord Bryon’s poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: ‘First freedom and then Glory – when that fails, | Wealth, vice, corruption …’ from Canto IV. In his depiction of the mountain as the point of continuity between the paintings, Cole changes the world around it completely. Over the course of the five pictures, Cole takes us from dawn to dusk and across the seasons.

In The Savage State, set on a Spring dawn, Cole gives us natives hunting, both on land and water. Deer are plentiful and the camp on the right side of the painting awaits the return of the successful hunters. At the centre right is the mountain, marked at its top with a boulder.

Cole: The Course of Empire: The Savage State

In The Acadian State, set in the morning of the spring or summer. Rather than chasing wild deer, civilization now cultivates sheep. A temple-like building smokes, and instead of hunting the visible figures are dancing or playing. The woman in white holds a distaff to process the sheep’s wool, and on the beach, a Greek-style oared boat has been drawn onto the sand and is a warning of the coming empire. An old man on the left, sketching with a stick, seems to be working on a geometry problem. The implications are that knowledge and religion have brought a civilizing effect to the landscape. The arts: math, drawing, dance, etc., are important. Behind the marker mountain, an even larger mountain is shown, reminding us, perhaps, that we are only looking at a microcosm of the world in this valley and waterway.

Cole: The Course of Empire: The Arcadian or Pastoral State

In The Consummation of Empire, shown at mid-day in early Autumn, we have arrived at the zenith of culture. In the foreground, a red-robed king (or general) crosses the bridge in triumph. Statues and temples proliferate, all with gold detailing, and the water is no longer a hunting ground but a pleasure ground, with luxurious boats with colour sails everywhere. Even the mountain has been tamed, with roads and villas lining its slopes. Nature is almost invisible under its ‘civilizing’ covering. The observer is now on the same side of the water as the mountain.

Cole: The Course of Empire: The Consummation of Empire

And then, it all fails. Destruction shows the city under siege, fire in the upper right, and destruction of the beautiful stonework at the bottom right. We are at the same point of view as in the previous picture, later in the day. Green banners on the temple side contest red banners on the palace site. A woman in white jumps to her death as a soldier vainly catches at her cloak; another weeps over her dead child. The lower left is filled with dragon-headed boats filled with soldiers. Above it all, the mountain stands.

Cole: The Course of Empire: Destruction

And now, at twilight, the landscape is empty of all humans. Nature is returning, claiming the structures that once blocked it out, crawling in ivy up the now-denuded pillar. Only birds populate the landscape now – nesting on top of the pillar, flying in the sky, floating around the little island, and a dark water bird in the lower right centre – hunting for its dinner. Humanity has destroyed itself. Nature, in the mountain and the wildlife, has outlasted mere mortals.

Cole: The Course of Empire: Desolation

In her string quartet built around these paintings, American composer Nell Shaw Cohen (b. 1988) was strongly affected by Cole’s vision. She saw the paintings at the New York Historical Society in 2008 and started writing almost immediately. Cohen always intended the music to be performed with the pictures and, in that juxtaposition, the composer hopes that ‘someone comes away from listening to my string quartet with a deeper sense of engagement with the paintings, and feels that they were able to enter the world of the paintings in a different way than they had before—similar to the way that a score reinforces the emotional and aesthetic experience of a film—then I would feel that my music was a success!’ Hidden in four of the five movements is a ‘mountain’ motif that is not used in the third (where nature has been supplanted by buildings).

Nell Shaw Cohen

Each of the five movements is based on a different music style: I. Medieval motet; II. Renaissance dance music; III. Baroque orchestral music; IV. ‘Bartók meets Led Zeppelin’; V. Ahistorical and abstract.

She ends the work with a final version of the mountain theme…and on an unresolved note, ‘hinting at a future era of uninhabited nature’.

The images by Cole are monumental: The paintings are at least 99 x 160 cm (39 x 63 in) and the highpoint of the series The Consummation of Empire is 129 x 193 cm (51 x 76 in). They were intended to surround the fireplace of Cole’s patron, Luman Reed, at his house on Greenwich Street in lower Manhattan. His collection became the basis of the public art collection that was eventually donated to the New York Historical Society in 1858.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter