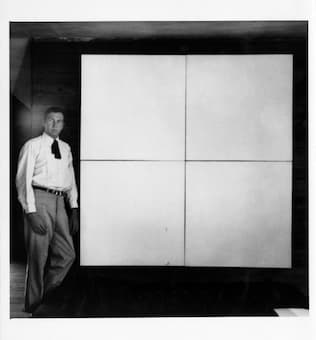

John Cage (1958)

Usually when we write about musicians and artists, we write about how one inspires the other, either how an artist might choose a musical work as the inspiration for his work or how a composer might choose to portray a painting in sound.

When we get to the works of John Cage and the paintings of Robert Rauschenberg, however, we have a third element that influences the work: chance.

Robert Rauschenberg with White Painting [4-panel]

Rauschenberg created 5 works in his set of White Paintings, each consisting of a different number of modular panels, appearing in one-, two-, three-, four-, and seven-panel versions. In each case the works are completely white, painted with everyday white house paint and paint rollers to achieve smooth, unembellished images.

First appearing simply as blank canvases and without content, the paintings can be gradually read as reflecting the rooms in which they appear. Rauschenberg’s aim was to create a painting that looked untouched by human hands, as though it had simply arrived in the world fully formed and absolutely pure. He expanded Cage’s reading by referring to the paintings as ‘clocks,’ and said that if one were sensitive enough, the subtle changes on the works’ surface could tell you things like how many people were in the room, what time it was, or what the weather was outside.

![Robert Rauschenberg: White Painting [3 panel] (1951) (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)](https://interlude-cdn-blob-prod.azureedge.net/interlude-blob-storage-prod/2022/01/White-Painting-3-panel.jpg)

Robert Rauschenberg: White Painting [3 panel] (1951)

(San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

Reaction to The White Paintings came immediately, which declarations that they were not art. Many viewers did not even perceive that they had been painted. One of the strongest supporters of Rauschenberg’s work was John Cage, particularly in his 1961 essay ‘On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Work,’ for the magazine Metro, where he asserted that “the white paintings were airports for the lights, shadows and particles” and noting that they “caught whatever fell on them.”

One of the most famous works by John Cage is 4’33”, written in 1952. Cage said that his decision to create this piece came after seeing Rauschenberg’s White Paintings. Cage’s work begins when the pianist sits at the piano and concludes 4 minutes and 33 seconds later. The keyboard lid is closed at the end of the first part, opened for the second part, closed, and then opened for the third part. It concludes when the pianist lowers the cover for the third time. The work is ‘meant to be perceived as consisting of the sounds of the environment that the listeners hear while it is performed.’

Cage: 4’33” (1960)

Just as Cage wanted us to listen to the ambient sounds in 4’33”, Rauschenberg wants us to read the ambient visuals in his White Paintings. In Cage’s work, we hear what is normally inaudible: the ambient noise of a concert hall is what we ignore when we focus on a piece.

The premiere of 4’33” with David Tudor at the piano, took place at the Maverick Concert Hall, Woodstock, New York.

The audience, not prepared to listen to itself, was restive and finally many people walked out. Cage, speaking after the performance said: ‘They missed the point. There’s no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence, because they didn’t know how to listen, was full of accidental sounds. You could hear the wind stirring outside during the first movement. During the second, raindrops began pattering the roof, and during the third the people themselves made all kinds of interesting sounds as they talked or walked out.’

Anechoic Chamber

The duration of the work was not random – Cage was basing it on the standard length of a piece of Muzak (pre-recorded ‘canned’ music). His first exposure to the idea of silence as a music entity came from experiments he did in the late 1940s. In 1951, he visited the anechoic chamber at Harvard University, expecting to hear silence. Instead, he heard himself: a high sound from his nervous system and a low one that came from the circulation of his blood. Silence, in short, was humanly impossible.

Actually, the ambient noise of a hall can be something to listen to, particularly if you’re in a concert where the audience gets bored with a piece. Listen to this some time: when an audience is enraptured, they’re absolutely still, with perhaps only the sound of a dropped program disturbing the performance. When an audience loses the orchestra, it’s audible: you’ll start to hear more noises of people shifting in seats, coughing, more sounds from the programs, and even, perhaps, talking.

With Cage teaching us how to listen more deeply and Rauschenberg teaching us how to look more closely, they both changed our relationship to art. Both artists require us to slow down, focus on what we actually hear and see, and listen and look for the subtle changes.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

It takes how far and bold one ventures in arts.