Greg A. Steinke: EXPRESSIONS on the Paintings of Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch (1863–1944) was an artist for over six decades. His final output consists of nearly 2,000 paintings, hundreds of graphics, and thousands of drawings. He was also a writer of poems, prose, and, most importantly, diaries. It’s these diaries that give us some of the interpretive clues to his sometimes difficult works.

American composer Greg A. Steinke took a phrase from Munch’s diaries about sight and extended it to hearing: ‘As stated in Munch’s Journal: “at times you see with different eyes,” thus, a composer “at times [hears] with different [ears.]”’. And so Steinke created his composition, Expressions on the Paintings of Edvard Munch as if ‘hearing’ these paintings at a moment in time. At another time, there may be a different way to hear it. With this in mind, Steinke gives the performers the possibility of creating different interpretations by creating passages of what he called ‘structured improvisation’ – different performances would mean different experiences for the listener.

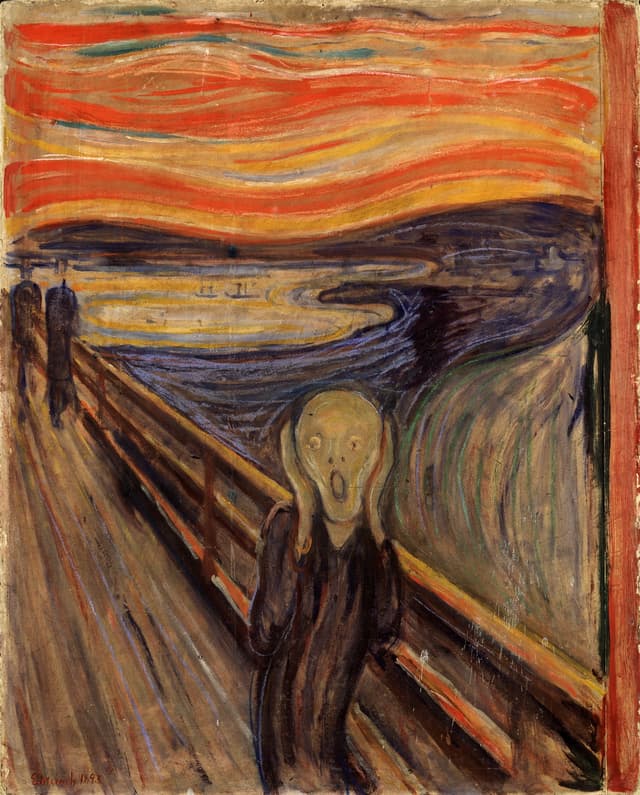

The first movement is based on what is probably Munch’s most famous picture. The Scream, a symbolist masterpiece, captures a moment that so many of us in the modern world identify with.

Edvard Munch: The Scream, 1893 (Oslo, National Gallery)

Munch wrote:

I was walking along the road with two

friends – then the sun went down

Suddenly the sky turned blood-red

– and I felt

a breath of melancholy

– an exhausting pain

under my heart – I paused,

leaning against the fence, tired to death – above the blue-black fjord and city there was blood in tongues of fire

My friends went on and I stood

there trembling

with anxiety –

and I felt that a great infinite scream went through nature

For an image that is seen by some as simplistic, its complex interpretation has extended for a long time. Munch himself worked on the image for a long time, with the eventual final painted form being deceptively simple. It looks as though it was painted quickly, based on both the painting technique and the lack of detail, revealing none of Munch’s extensive work. The image has become so familiar that it is an even more simplified emoji, but which captures the empty eye, the oval mouth, and the hands, albeit in a lower position and not around the ears. Since, as we know from Munch’s writings (above), the figure itself is not screaming but reacting to the scream he hears from nature, the change in hand position is actually significant.

Face Screaming in Fear Emoji (U+1F631)

In Steinke’s musical version of Munch’s painting, he builds the scream into the music through repeated notes, many at a high pitch, with the lower strings reflecting the painter’s internal turmoil.

Greg A. Steinke: EXPRESSIONS on the Paintings of Edvard Munch – No. 1. The Scream (1893) (Image Music No. 17) (ÉxQuartet)

The second movement is based on Munch’s 1899 picture, Dance of Life.

Edvard Munch: Livets danse (Dance of Life), 1899 (Oslo, National Gallery)

The picture, read from left to right, takes us from a single young woman on the left in a light floral gown, through early love, married love, and then mature love, until she’s left alone again, a solitary figure in black on the right. The sun, carefully positioned to the center-right, shines on youth, whereas old age gets shadows and darker colours.

Steinke carries the idea of a repeating lively dance but with dark overtones.

Greg A. Steinke: EXPRESSIONS on the Paintings of Edvard Munch – No. 2. The Dance of Life (1900) (Image Music No. 17) (ÉxQuartet)

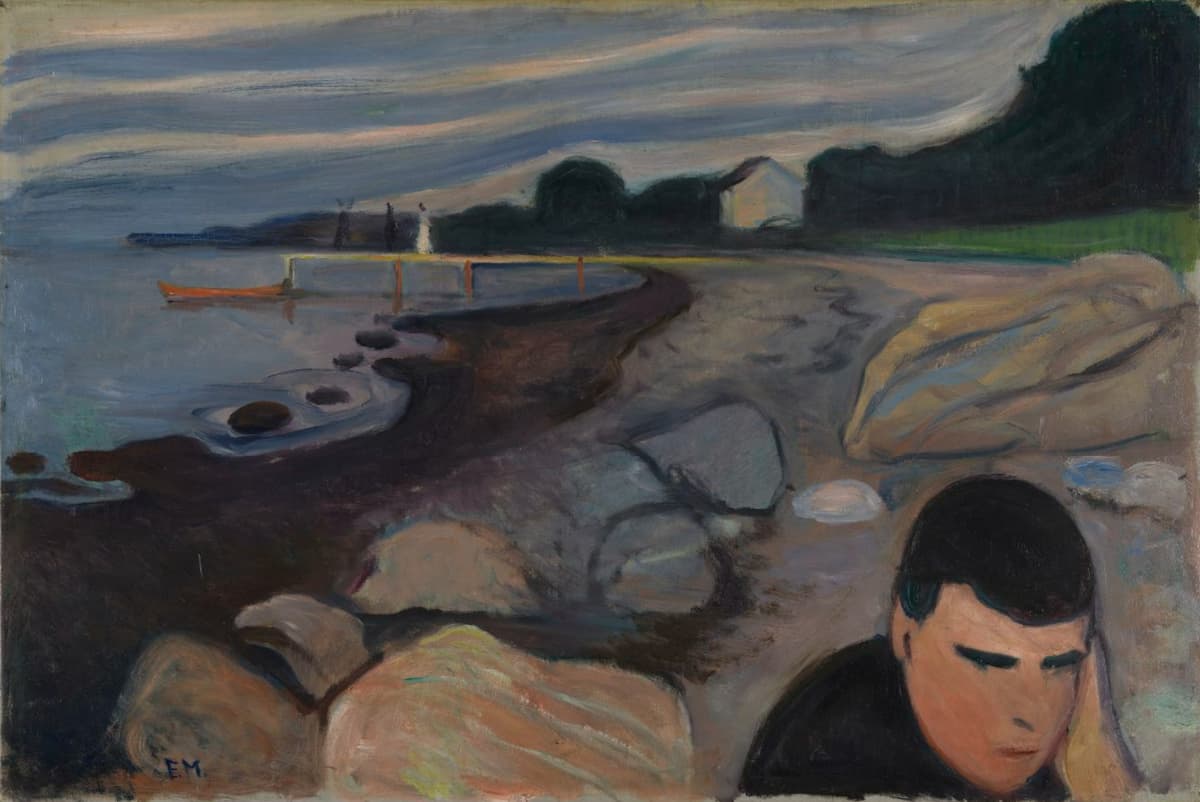

The last inspiration is a less-familiar picture, the 1892 Melancholy. Another symbolist painting, it depicts a summer night, with the striated colours dispersing the bleu overheard. In the foreground is a simple figure of a man, holding his ear, and turning his back on the score and the figures on the jetty. Munch’s diary lays out the scene:

I was walking along the shore – the moon was shining through dark clouds. The stones loomed out of the water, like mysterious inhabitants of the sea. There were large, broad heads that grinned and laughed. Some of them up on the beach, others down in the water. The dark, bluish-violet sea rose and fell – sighs in among the stones … but there is life over there on the jetty. It was a man and a woman – then came another man – with oars across his shoulder. And the boat lay down there – ready to go.

Although seeming to describe the scene presented, the three figures actually refer to a couple for whom a third person has interrupted: the ‘content refers to Munch’s friend Jappe Nilssen and his unhappy love life around this time’. The painting is symbolic but not representational, and we sense Munch’s unhappiness with the situation as he turns his back on it, even at a distance.

Edvard Munch: Melancholi (Melancholy), 1892 (Oslo, National Gallery)

Steinke’s movement doesn’t reflect the peacefulness of the scenery but the angst that is hidden in plain sight.

Greg A. Steinke: EXPRESSIONS on the Paintings of Edvard Munch – No. 3 Melancholy (1892) (Image Music No. 17) (ÉxQuartet)

Steinke chose difficult images to put into music but his technique of structured improvisation gives us a way to approach the paintings with different viewpoints. If you’re in the middle of a breakup, Melancholy will speak to you differently than if you only associate the figures with friends.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter