Carlos Simon: The Block

In 1971, American artist Romare Bearden looked out the window of his friend Albert Murray’s Lenox Avenue apartment and was inspired to create an epic narrative out of something that was very familiar and ordinary: a window view of Harlem between 132nd and 133rd Street. The view is not meant to represent just that block but the liveliness of all of Harlem.

Romare Bearden

The work is enormous: 121.9 × 548.6 cm (48 in. × 18 ft.), and in this picture of the artist in front of his work, you can get an idea of its size.

Romare Bearden in front of The Block, 1971, as shown at the Museum of Modern Art in Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual

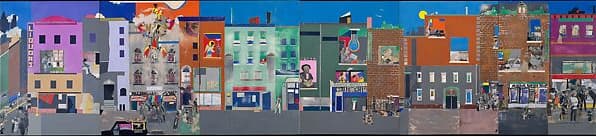

Beardon has created in collage, a virtual panorama of one city block in New York.

Bearden: The Block, 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

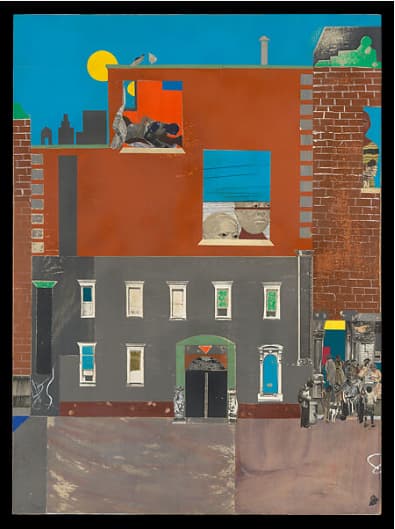

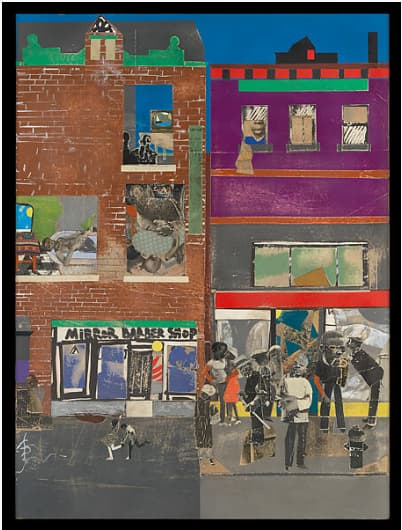

The work was created in six separate panels to be exhibited together to create a continuous scene. At street level, business and institutions have their place: a liquor store, a church, a barbershop, while in the rooms above, we look into rooms and see the private lives of the people.

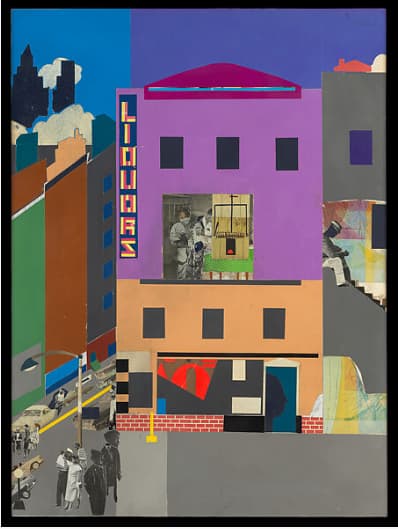

Bearden: The Block (detail 1), 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

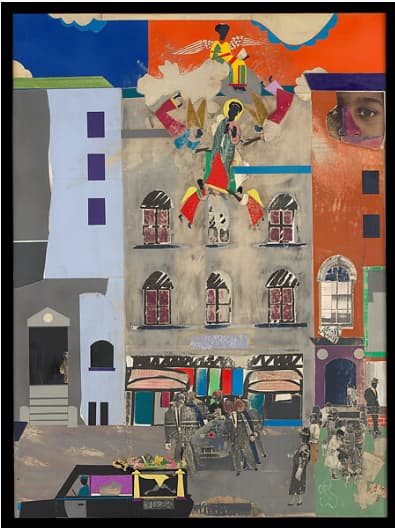

Bearden: The Block (detail 2), 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

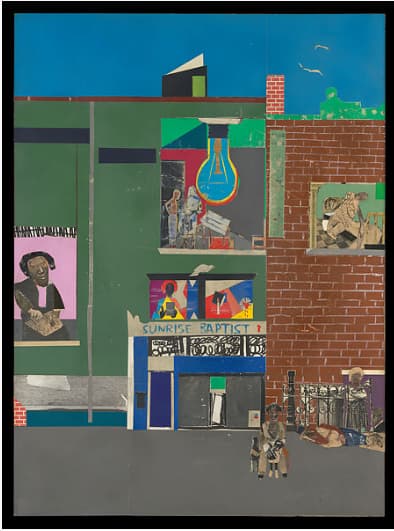

Bearden: The Block (detail 3), 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bearden: The Block (detail 4), 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bearden: The Block (detail 5), 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bearden: The Block (detail 6), 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

One writer on the collage said: ‘He wants you to focus on the entire composition, but also see the small, little, human moments that are happening. By showing a giant child’s face, or children in a window with a giant mousetrap, it makes you look at them more carefully than if they were in proper scale, and makes you wonder what’s going on in their lives behind those tenement walls’. There are also elements in Bearden’s work that are more metaphysical, such as the angel waiting above the church to carry the soul of the departed to heaven (detail 2 above). Children run and play in front of the barbershop (detail 6 above) while next door, man gather in discussion or to look at their new haircuts. Life is all around.

The Block was originally exhibited with sound and was accompanied by an audio of the sounds on the street, including news broadcasts, babies crying, dogs barking, people talking, a church service, music, cars going by, and so on. The sounds effects and on-the-street recordings were merged into an 8-minute collage soundscape. Created by Daniel Dembrosky for Bearden, the recording was lost for many years and was only recently discovered and put on the Met website in 2024.

RECORDING on this website: https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/articles/2024/02/romare_bearden_the_block

The collage, made of ‘cut and pasted printed, colored and metallic papers, photostats, graphite, ink marker, gouache, watercolor, and ink on Masonite’, as the Met Museum description has it.

American composer Carlos Simon has made his own version of The Block. His orchestral study was made in 2018 before the original soundtrack was relocated. Simon’s block picks up on the excitement in the city. It brings to life the static images in the collage: a funeral procession, children at play, a couple embracing in bed, and people convening in front of a storefront, which is revealed through a close study of Bearden’s work.

Carlos Simon

As a contrast to the literal sounds in the 1971 soundscape, Simon’s symphonic work brings a dimensionality to the work – while the woodwinds are doing one thing, the brass are focused on something else, the violins add their colour, and behind it all the percussion drives on.

Carlos Simon: The Block (National Symphony Orchestra; Gianandrea Noseda, cond.)

The poet Major Jackson wrote a poem based on Bearden’s work. Like Bearden, Jackson also saw the sound element of the collage.

MajorJackson (photo by Beowulf Sheehan)

His poem, The Block, brings out all elements of the work: images, colours, and the sound.

A village though, holy presence

in the bricks, to see through walls

with our eyes. Bodies assembled such that traffic

stays on the margins but the bright river,

though stilled on one Harlem avenue, flows out

from thresholds and doorways

where penny-colored faces profile like noble silhouettes,

and thus, this tension between life’s rush

and final doom. Someone has died,

and a hearse awaits, Bearden seems to say,

for us all, swimming with his mouth wide open.

No smirks from those enamored of the panorama.

To cross a corner, to sit sullen

on a staircase, to grasp a child from behind

weaves a cherished landscape of propositions.

A mother is half a Madonna,

and a blue bulb’s filament looms above the saints

of Sunrise Baptist whose hymns are unheard melodies,

whose prayer book, candle, altar

fix us to Southern roads. Why leave

when so much is here to observe?

The syncopated dailiness is Greek in proportions.

Even a barbershop serves a mirror,

all snips and shears and fades.

We, too, resurrect and ascend

and shake hands with Ethiopian angels,

and what carries the music

of our ascension is life, an improvised

resurrection, a colorful bricolage

of ritualistic seeing, tenements played

like keys, a communal blues, our imperative

for tenderness, lovemaking at dusk,

a billowing curtain serene as a kiss.

Here, there are no secrets.

These bodies in repose, bodies rising from

metal frame beds, bodies soaking in tubs,

bodies watching TVs as boats sail on,

children hovering above hopscotch squares,

what are they but the affirmative dream

of a city whose arrivants are dignity personified?

Look closer, look in:

animals are here, too.

A yellow pigeon coos on an awning,

another pair on a rooftop,

seagulls lift and angle into thermals,

a dalmatian stands beside a boy

as if in a Brueghel.

The tenements on Lenox between 132nd and 133rd

proclaim the flaneur’s feast: a mother calls down

from a window to remind her daughter

of ingredients for potato pone, pork belly, and cow peas.

At the corner store, a couple leans

against glass oblivious of the nearby crowd

seeming to convene a second line.

We are not without our vices

so says the neon Liquors sign

and the blanketed man who’s made concrete his bed.

Several floors above,

a mousetrap is a window

that wants to ambush a setting sun.

But the old folk from the fields

hold sentry like F. Douglass in portraiture,

and H. Tubman, and may we

revere them, may they occupy the periphery

of our vibrant canvases.

We are entangled in geometric shapes.

Our limbs are their limbs.

In cities, feelings pass through walls

For an idea of what that block looks like today, Google Streetview provides an answer.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Lenox Avenue between 132nd and 133rd Streets, March 2023 (Google Streetview)