Inspirations Behind Barry Guy: After the Rain

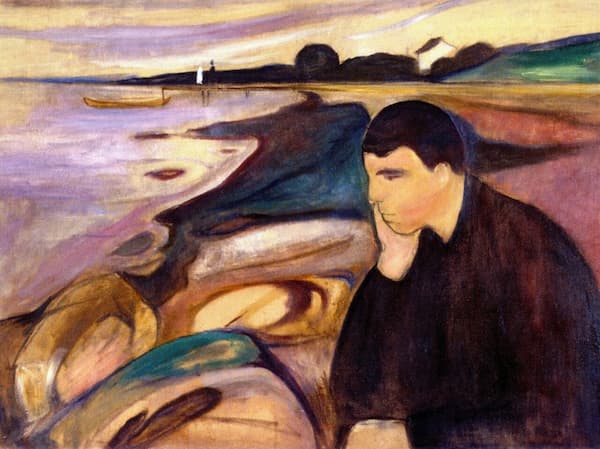

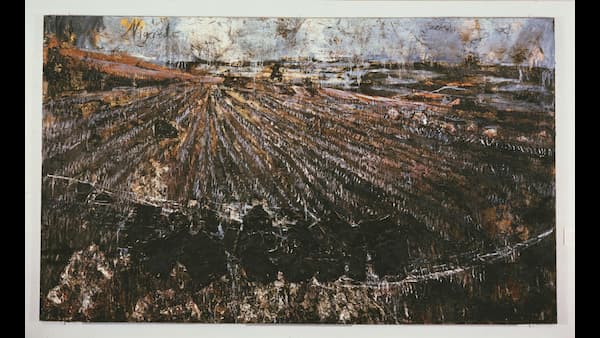

German artist Max Ernst (1891–1976) created two major pieces entitled Europe After the Rain.

Max Ernst

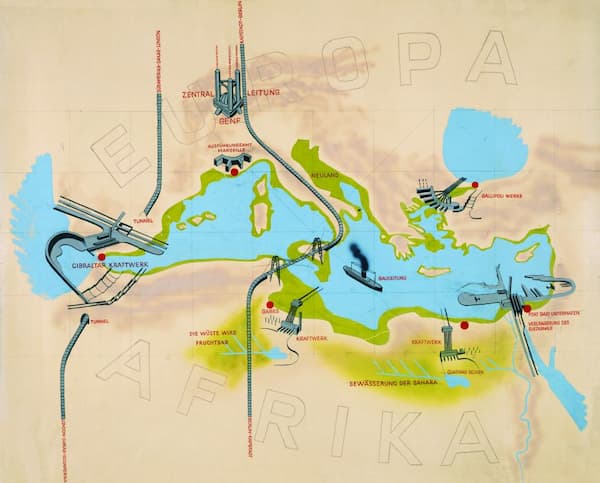

The first, in 1933, is a collage of oil and wood, refiguring the map of Europe. Although many believe that this is a commentary on the rise of Hitler in Germany and foretells the catastrophe that would engulf Europe, others see it as a realisation of an idea from Herman Sörgel, Atlantropa.

Sörgel proposed a giant engineering project that starts with the closing of the Mediterranean Sea at the Straits of Gibraltar, lowering the Sea’s level, and reclaiming land now underwater. All the land that now edges the Mediterranean would expand, and former seaside cities would become land-bound, including Venice. Huge hydroelectric plants at Gibraltar and the Sea of Marmara would supply power for Europe, and there would be more land for farming and new cities. In the end, however, this monumental project was deemed too expensive for the German state to take on and, after the war, the rise of nuclear power made hydroelectric power less interesting. Sörgel continued to pursue the project through the early 1950s.

Sörgel: Altantropa, Exhibition Poster, 1933

Ernst: Europe After the Rain I, 1933 (private collection)

In 1941, Ernst created another image of Europe After the Rain. It’s a very different concept from the first map-like work.

Ernst: Europe After the Rain II, 1941 (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Athaneum)

More so than any other art style, Surrealism was well equipped to deal with the total destruction of the civilised world that WWII meant, and Ernst caught this in his second painting.

The primary technique Ernst used in this painting was decalcomania, where he would apply painted glass to his canvas and then slowly pull it off, resulting in images that could be then further painted. One writer described the work thusly:

…the piece is difficult to read in reproduction, but the figures that leap out include the bird-headed spear carrier looking to the left, perhaps at the armless nude with her back turned and flat-topped hat, perhaps at the central pillar’s verdigris breasts. Below, a bull seemingly on rails lies crushed under a pavilion like a rotting merry-go-round holding another nude female torso inside. To the left, five women wearing ornate dresses and hats lounge in sandstone hollows.

The words ‘perhaps’ and ‘seemingly’ figure large in this description because, as in many surrealist pictures, the reading can be independent for each viewer. Yet even with his own absence from the continent (he was able to escape Europe via Portugal with the wealthy collector Peggy Guggenheim whose family had sent a private plane), Ernst could imagine what was happening across Europe.

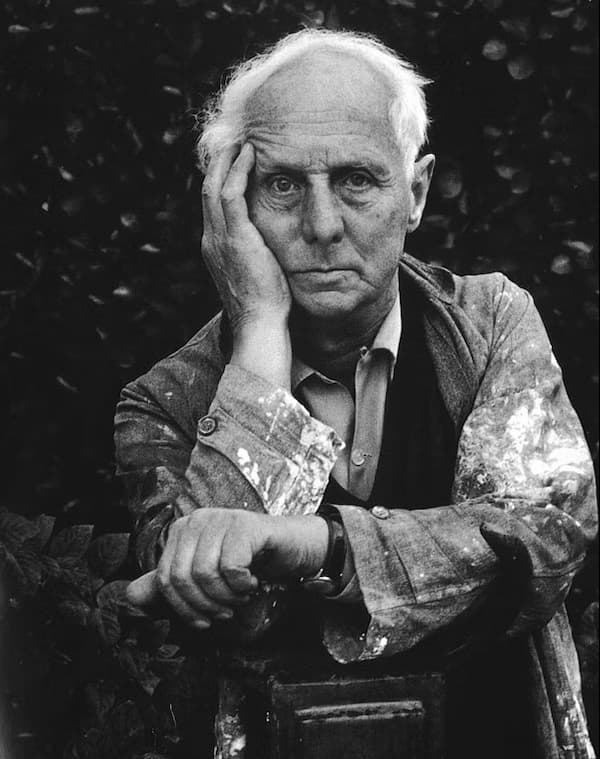

English composer and double bass player Barry Guy (b. 1947) saw Europe After the Rain in an exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London in 1991. His 1992 work, After the Rain, was influenced by that viewing. It was commissioned by Richard Hickox and the City of London Sinfonia for their 20th anniversary.

Barry Guy (photo by Dmitrij Matvejev)

Guy’s description of the painting shows what he was reacting to:

‘The canvas portrays four large masses of tortuous baroque-like remains as if left after some unfathomable catastrophe which are somehow held in a non-violent state of animation. In many of Max Ernst’s paintings there are half-hidden images submerged in the exquisite details. These images invite the viewer to speculate on the nature of events. Here in Europe After the Rain could be the apotheosis of anxiety and destruction or the emergence of new life from the ruins. I am drawn to the latter.

He broke his orchestral work into 10 movements in 4 sections, modeled on Renaissance music, with recurring sections (Refrain), and other titles from sacred music: Chorale, Antiphon, Motet. The four main sections:

- I. Refrain / II. Chorale / III. Antiphon

- IV. Refrain / V. Chanson

- VI. Canon / VII. Antiphon

- VIII. Motet /IX. Antiphon / X. Refrain

Barry Guy: After the Rain – I. Refrain (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

The following Chorale seems to fall from the sky in the violins, but, below it, the solid ground holds in the lower strings.

Barry Guy: After the Rain – II. Chorale (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

In the Antiphon, we’re in the middle of a conflict. The held pitches begin to fall, and are we under attack or in the bomber itself? It’s a familiar sound from a hundred different war movies, but in this context, it’s somehow more personal. The pitches rise again and begin to twitter–flight or birds?

Barry Guy: After the Rain – III. Antiphon (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

We return to the Refrain for the start of the second section. Its accompanying Chanson, seeks definition – is it a song of thanks for escape? For redemption? For a pause in the fighting?

Barry Guy: After the Rain – V. Chanson (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

The distinctive lines of the Refrain are remodelled in the Canon with a change of tempo and focus for the start of the third section.

Barry Guy: After the Rain – VI. Canon (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

The Antiphon, with its wavering pitches, ends the third section very abbreviated.

Barry Guy: After the Rain – VII. Antiphon (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

The final section starts with the Motet, built on long polyphonic lines. The longest movement of the work seems to be showing us Ernst’s masterpiece as it is today, not what it took to create it. Midway through the movement, the atmosphere changes and is more fraught. The despair of memory? The despair of the present? Or the realization that tomorrow can change everything?

Barry Guy: After the Rain – VIII. Motet (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

The sliding pitches of the Antiphon are now stilled, moving slowly over a long set of bass notes. Everything is settling in place again.

Barry Guy: After the Rain – IX. Antiphon (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

We close with a return to the frenetic opening Refrain, but this time with a conclusive ending.

Barry Guy: After the Rain – XI. Refrain (City of London Sinfonia; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Guy has taken a work of art that is considered one of the most important Surrealist paintings to confront the war and its future aftermath, and created an orchestral piece that delves into Ernst’s images, either real and present or implied. It has the effect of drawing you deeper into the painting’s world, but doesn’t quite end with a promise that the future won’t hold this kind of horror again.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter