The great thing about being a practicing musician is all the music you have at your hands. As a 10-year-old travelling musician, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) found himself bored on a trip from London back to Salzburg.

Louis Carrogis Carmontelle: Mozart family on tour: Leopold, Wolfgang, Nannerl, ca 1763

When they arrived in The Hague, The Netherlands, it was just in time for the enthronement of William V, Prince of Orange. The enthronement represented William’s coming of age, as he had been ruler of the Dutch Republic, with regents, since he was age 3. From 1751 to 1766, William was overseen first by his mother, then his grandmother, then the Duke Louis Ernest of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and, finally by his sister, Princess Carolina, who was 5 years older than William.

Jacques Firmin Beauvarlet: Portrait of Willem V, Prince of Orange, 1765 (Washington: National Gallery of Art)

For the festivities, Mozart created a quodlibet, a work that combines popular melodies of the day, called the Gallimathias musicum, K. 32, (Musical Gallimaufry or mélange). It brings together in swift sequence 17 different melodies. Some of these tunes would have been well-known melodies while others would have been private references or even private jokes. For a 10-year-old creating one of his first orchestral works, it was a wonderful portent to what was in his future.

No. 3 gives the horns a starring role. Mozart quotes his father’s Peasant Wedding in No. 4, invoking the sound of the hurdy-gurdy in the open fifths in the viola before a graceful set of oboes elevates the mood.

The link between Nos. 5 and 6 is deliberately gauche. No. 7 quotes a drinking song.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Gallimathias musicum, K. 32 – Nos. 1-7 (John Constable, harpsichord; Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

No. 8 is set with words that are nonsensical: Vanity! Vanity! Eternal ruin! When everything is boozed away, no inheritance is left, presumably to be sung by the players. No. 9 uses a hunting melody (bawdy, of course) called ‘Castrating a Boar’ with hunting horns and answering woodwinds.

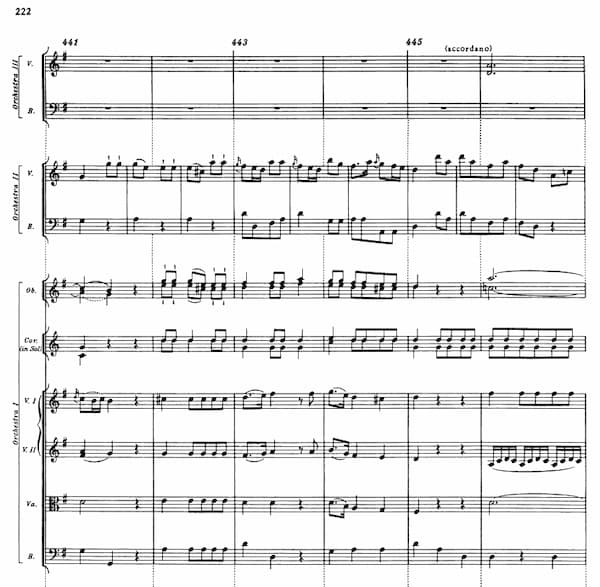

No. 10 is based on a piece by Johann Ernst Eberlin. The beginning of No. 11 is a quotation from the beginning of the final Presto movement of Leopold Mozart’s Symphony D 20. No. 12 is an original Mozart piece of contrapuntal writing, which introduces No. 13, a keyboard solo for himself. No. 15 is also based on a piece by Johann Ernst Eberlin. The intentionally bad transition hits again between Nos. 15 and 16 where the final chord is missing.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Gallimathias musicum, K. 32 – Nos. 8–16 (John Constable, harpsichord; Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

The final movement, the fuga, shows the young master at work. The source for the melody was a song in praise of William V: Willem von Nassau, which Leopold wrote was the song that everyone was singing.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Gallimathias musicum, K. 32 – No. 17: Fuga (John Constable, harpsichord; Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

The Gallimathias (or Galimatias) is a work of nonsense, a hodgepodge of music created by Mozart as a 10-year-old. The variety of sources he quotes, starting with his father’s music, is impressive. What’s more impressive is the use of the sung text in No. 8. This was a brand-new idea – inserting sung music in an otherwise straightforward orchestral piece. As would later be used in other joke pieces, deliberately bad writing for its humour value was a part of this work. It’s been described as ‘a kind of burlesque miniature symphony’ and that seems to cover it nicely.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter