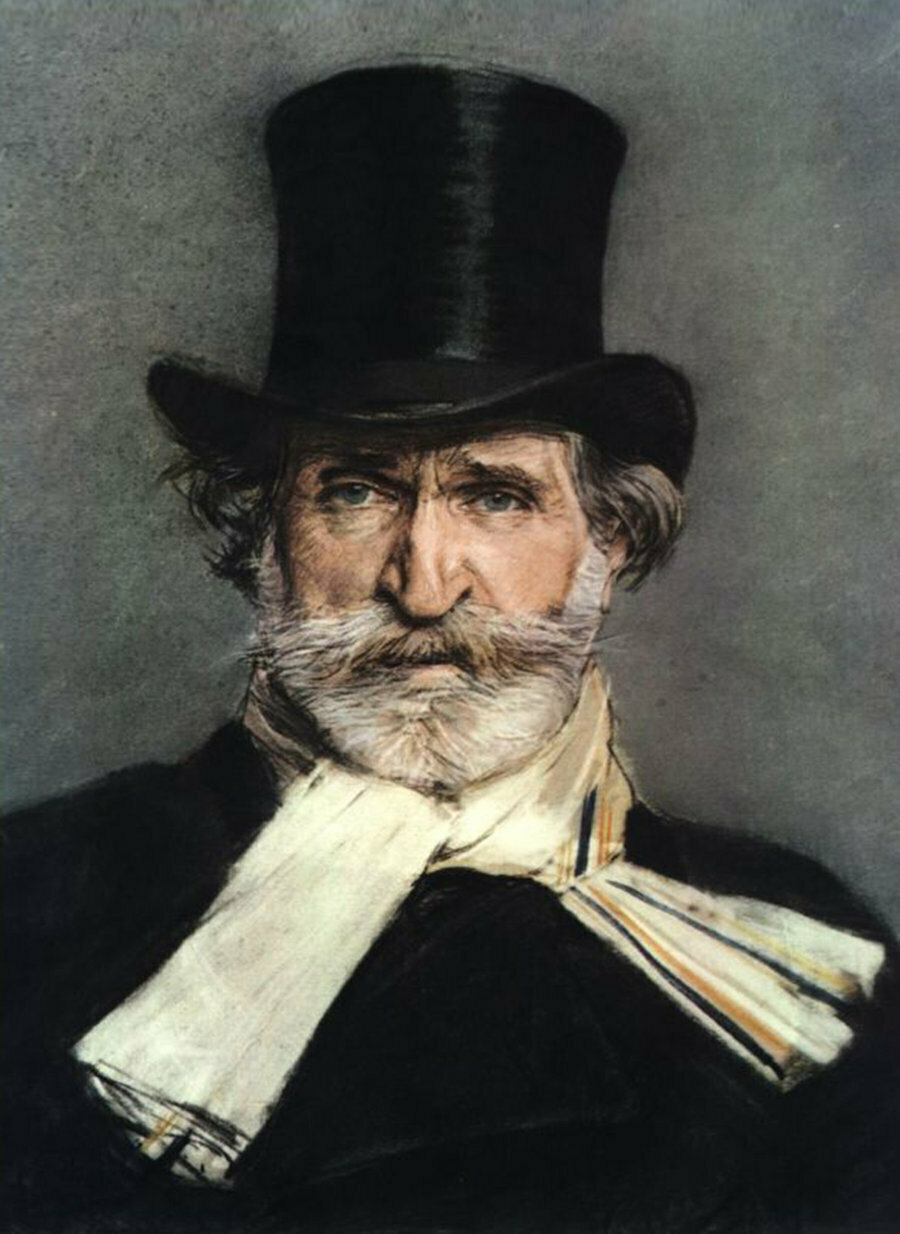

Deborah Kerr and Marni Nixon

West Side Story

Leonard Bernstein

It was announced in the spring of 2012 that the Indianapolis Symphony would include in its upcoming Pops Series three “live” performances of the 1961 classic movie West Side Story, with music by Leonard Bernstein, choreography by Jerome Robbins, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and original book by Arthur Laurents. This was not the first time that we were going to get to play a movie soundtrack’s score, since we had performed such selections when some composers would come to Indy with baton in hand to conduct us. Nick Conti, Aaron Copland, Jerry Goldsmith (I had him autograph my cherished LP of the soundtrack for The Trouble With Angels), and John Williams had done so. But this time it was to be David Newman, part of the composing Newman Dynasty, who was to be on the podium. What was unique about this particular weekend of concerts was that we were to be playing the entire film score, while the film itself ran on a huge screen over our heads – for 152 minutes.

In the past few years we have done film-concert performances with Indiana native, George Daugherty, who travels the world with his award-winning “Bugs Bunny at the Symphony” productions, and we’ve done The Wizard of OZ. But in both cases, it wasn’t almost-continuous playing, and we had time to sit back, relax a bit, and actually be able to watch parts of the movies overhead. But for West Side Story, it was pretty similar to playing an opera, with the music running almost non-stop, with a pause only every few minutes or so.

Playing along with a film running overhead isn’t simply “karaoke in reverse,” with us just watching the conductor for starting, stopping, and changes in tempo. When there are singers and dancers overhead, it is an incredibly complicated scenario of coordination, not only for those of us onstage, but also offstage, and prior to the concerts. Musicians and technicians have spent thousands of hours just getting the production simply to … work. In the case of West Side Story, the pre-concert preparation itself is worthy of a book, or even a movie.

I recently spoke on the phone with Eleonor Sandresky, Associate Producer for the project for The Leonard Bernstein Office, and with the production’s audio engineer, Matt Yeltin. For years, movie and Broadway show buffs have known the inside secret that star Natalie Wood did not actually sing what we hear coming out of her mouth onscreen: it was the ghosting songstress Marni Nixon, who had also been the singing voices of Deborah Kerr in The King and I, Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, and even Marilyn Monroe when she breathed, “These rocks don’t lose their shape, diamonds are a girl’s best friend!” In the case of the role of Maria, Miss Wood indeed did pre-record all of her songs, ostensibly to later be inserted into the film itself. But there was a glitch: as Natalie’s husband, Robert Wagner, allegedly said to her after experiencing a rough cut of her performance, “Sorry dear, it’s just not good enough.” (Please pay a visit to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DYvgA5hZTVI. Time marking 2:00 is rather… enlightening!)

Nathalie Wood

David Newman had conducted the debut of this newly-designed production in July of 2011 at the Hollywood Bowl. Following performances there with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, he and other conductors have since taken the show on the road, with presentations with the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, in Sydney, Australia, and here in Indianapolis. During our first rehearsal with him on November 14, David told us how crucial it was for us to wear headphones for the entire performance to hear what is called the “click track.” The dance sequences and Miss Wood’s “creative” counting and use of rubato (actually rather endearing) made her songs especially difficult to follow, even with a conductor guiding us through the score.

Ms Sandresky and Mr. Yeltin filled me in on some of the lesser-known facts about how this production came into being for its 50th anniversary presentations. The film’s orchestral tracks were originally recorded with the singers’ voices being “layered” on at a later time. In the case of Natalie Wood, that star believed that her pre-recorded tracks indeed would be heard throughout the film. However, Ms Nixon had also pre-recorded the same vocal tracks to be inserted where Miss Wood’s ostensibly were to go. By the time the film’s prints had been mastered to be sent to theaters, all of the recording tracks of dialogue, orchestra score, and singers had been compressed into one, monophonic track that was actually part of the film itself.

For the present-day venture, digital technology came into play: Source Technology was used to “take the original monophonic soundtrack and remove the orchestral elements,” while keeping all other audio intact. According to Eleonor Sandresky, “This was actually done by a French company called Audionamix. Chace Audio by Deluxe took the new tracks, sans orchestra, rerecorded some of the foley (fence rattling, etc.), and wove them into a mix of old and new recordings to create the mix that was heard in LA and NY, although The LBO then had to go back and remix it for the concert hall.”

But the music score – the actual notes the conductor and players read – no longer existed, having been delegated to a landfill during the 1960s, along with other musical scores, costumes, and scenery from the massive MGM Studios in Culver City, California (See the note below). The musical score itself had to be recreated. And then it had to be somehow “linked” to what would be played in live performance, while the restored movie was being shown. Developed by David Newman and fellow-composer Kristopher Carter, the system of audible clicks heard by the conductor and headphone-wearing musicians ran simultaneously with the film. And on a video monitor, positioned by the conductor and his musical score, ran visual cues: known as “streamers” and “punches,” these significant light flashes and veri-colored lines alert the director to every musical cue, tempo, and “unexpected” change that has to be communicated to their players with that all-so-powerful baton.

And that is a brief idea of what had to take place before my colleagues and I could even sit down to … play along with a movie! With rehearsals lasting three hours, we were able to do two read-throughs before our first performance. Fortunately for us and for David Newman, we had already played the majority of West Side Story’s music in other incarnations – various medleys and the incredibly difficult Symphonic Dances created by Bernstein himself, and now a standard part of the classical repertoire. All we had to do in most cases was rely on our collective muscle memory from all those other versions we had played on countless concerts, adapt as we musician always do, and go on with the show. And we DID!

[Taken from the website http://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/music/mlsc/collection.cfm?id=262&f=x: “… music used for silent film, including printed dance band arrangements (scores and parts), sheet music, and other published and some unpublished music; 137 boxes of sheet music, choral editions, and other published and unpublished music used as a music reference library; 47 boxes of books, mostly about music, frequently stamped with “Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Music Library”. Many of these books are signed by the authors. Many more are signed by George Schneider, Music Librarian at MGM from 1928-1956, who founded and developed the MGM Music Library, which by the late 1940’s was one of the largest music collections in the country. This great library was sent to landfill in the ‘60’s as part of what has been called the “MGM Holocaust,” the tragedy that destroyed most of the great manuscript scores composed for MGM films.]

I Feel Pretty – Natalie Wood ‘s own voice – Jet Song – Russ Tamblyn s own voice