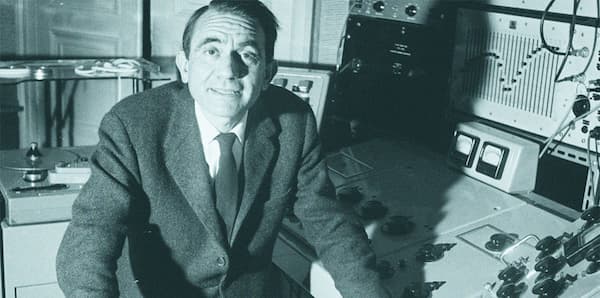

These words would commonly be heard issuing from the mouth of the composer at a rehearsal for one of his pieces. And if you’ve ever heard the music of Morton Feldman, you’d probably understand why.

These words would commonly be heard issuing from the mouth of the composer at a rehearsal for one of his pieces. And if you’ve ever heard the music of Morton Feldman, you’d probably understand why.

Feldman’s music is more often than not – well, almost absolutely always – extremely soft and delicate. Towards the end of his life he began to experiment with the idea of duration (very different to the idea of ‘form’, according to him), so while you might not want to commit 5 hours of your time to his second string quartet quite yet, there’s definitely a way in to his compositions if you approach them in the right way.

Sadly, people often lump Feldman together with John Cage, that famous avant-garde composer, and while it’s true that Feldman and Cage were good friends and that Feldman was inspired by Cage in the early days, their music became evermore divergent, with Feldman increasingly exploring his own individual ideas.

It’s easy to be scared when faced with a piece of Feldman, but as long as you’re not expecting the same listening experience as a Tchaikovsky symphony or Debussy prelude, then you’re in for a treat. Let me explain.

Feldman was obsessed with the idea of sound, something that came to the fore when he was exploring extreme durations. He once said ‘I don’t know what a flute is unless the person plays it for me’. Music was still an act of creating something, unlike Cage who was more into the idea that music existed all around us constantly in every sound that life throws at us: a door slamming; a car horn; the sizzle of bacon frying in the pan.

With this in mind, Feldman’s works become an exploration of musical sounds themselves – when held for such a long time, the note G-sharp ceases to be a G-sharp, and becomes an entity in its own right.

With this in mind, Feldman’s works become an exploration of musical sounds themselves – when held for such a long time, the note G-sharp ceases to be a G-sharp, and becomes an entity in its own right.

Many people describe listening to Feldman’s music as an ‘intimate’ experience, and this is a fairly accurate description. I discovered that if I embraced his music as something totally unique, delicate and intimate, I gave myself a chance to actually appreciate it, rather than going in there with the assumption that it’s just slow and boring. It’s all in how you look at it.

Rothko Chapel

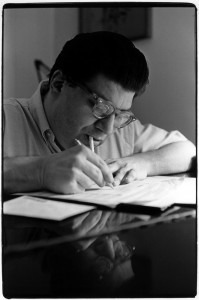

Rothko Chapel, a work of Feldman’s from 1971, is in some ways typical of his output, but in others totally bizarre. It’s scored for solo viola, percussion, celeste and wordless choir – this kind of scoring is fairly typical for Feldman. The solo viola guides us through the piece, with broad, soaring lines, interspersed with minuscule rattles, taps and chimes from the percussion. The wordless chorus sings haunting chords – chords that are so dense that you can’t pick out individual notes, and although the piece lasts for about 20 minutes, it seems to stretch on into eternity (in a good way!). However, in the last 2 minutes of the piece, a vibraphone sets up a hypnotic ostinato and the viola enters playing a simple song-like melody. The pure simplicity of this repeated pattern again gives an endless feel to the music – something truly beautiful.

Clocking in at 20 minutes, this is one of Feldman’s shorter works, which makes it a good way in to his oeuvre. However, don’t be scared of tackling something a bit longer – or a lot longer! Try and forget the argument that this kind of music ‘isn’t supposed to be listened to’. It is supposed to be listened to, but just in a different way. Listening to Feldman’s music can be either inspiring or frustrating. I’m not saying ‘If you don’t like it then you’re doing it wrong’ – of course you’re entitled to dislike it! However, many people don’t enjoy it because they don’t approach it in the right way, rather than the music being unlikeable, and whilst some of Feldman’s works are more accessible than others, they all share a timeless beauty, unique in the twentieth century repertoire.

You May Also Like

-

In Touch with Juliet Fraser British soprano Juliet Fraser is one of today’s most interesting and diverse singers. Though comfortable in many styles, it is her work in contemporary music that has garnered the most attention.

In Touch with Juliet Fraser British soprano Juliet Fraser is one of today’s most interesting and diverse singers. Though comfortable in many styles, it is her work in contemporary music that has garnered the most attention.

More Blogs

-

The Music That Surrounds Us Discover how everyday noise became revolutionary music

The Music That Surrounds Us Discover how everyday noise became revolutionary music -

Augusta Holmès: A Composer Who Wrote Music Bigger Than Life “I must show the males what I’m made of!”

Augusta Holmès: A Composer Who Wrote Music Bigger Than Life “I must show the males what I’m made of!” -

Classical Music Unfinished and Restored IV Why did Schubert leave so many works incomplete?

Classical Music Unfinished and Restored IV Why did Schubert leave so many works incomplete? -

The Trinity of Music Deepen your understanding of music's fundamental elements here

The Trinity of Music Deepen your understanding of music's fundamental elements here