Francis Poulenc and Jean Cocteau

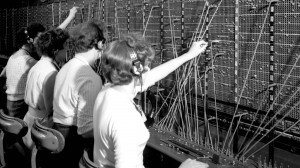

When the French poet, novelist, dramatist, designer, boxing manager, playwright and filmmaker Jean Cocteau wrote the play La Voix humaine in the 1930s, the telephone was the only option for instant vocal technological communication. At that time, the nature of the phone system was rather frustrating. Telephone lines were controlled by switchboard exchanges, so, rather than dialing direct as in present day, an operator was required to connect calls. Phone lines shared multiple subscribers, called party lines. Therefore, other subscribers could access another subscriber’s line when trying to make their own phone calls. A contemporary user wrote, “The telephone tests the endurance and feasibility, even the possibility of authentic human to human connection in a world increasingly enamored with technology.” Cocteau’s play allows us to eavesdrop on a stylish and sophisticated woman who makes a final phone call to the man who kept her as a mistress. Her ex-lover is getting married the next day, leaving the woman alone, distraught, and suicidal. The telephone plays a central role in the play; a dehumanizing object that feeds Elle’s anxiety, the lover’s unheard voice, and a terrifying weapon that produces trepidation. Ultimately, the telephone becomes the actual instrument of her suicide.

When the French poet, novelist, dramatist, designer, boxing manager, playwright and filmmaker Jean Cocteau wrote the play La Voix humaine in the 1930s, the telephone was the only option for instant vocal technological communication. At that time, the nature of the phone system was rather frustrating. Telephone lines were controlled by switchboard exchanges, so, rather than dialing direct as in present day, an operator was required to connect calls. Phone lines shared multiple subscribers, called party lines. Therefore, other subscribers could access another subscriber’s line when trying to make their own phone calls. A contemporary user wrote, “The telephone tests the endurance and feasibility, even the possibility of authentic human to human connection in a world increasingly enamored with technology.” Cocteau’s play allows us to eavesdrop on a stylish and sophisticated woman who makes a final phone call to the man who kept her as a mistress. Her ex-lover is getting married the next day, leaving the woman alone, distraught, and suicidal. The telephone plays a central role in the play; a dehumanizing object that feeds Elle’s anxiety, the lover’s unheard voice, and a terrifying weapon that produces trepidation. Ultimately, the telephone becomes the actual instrument of her suicide. When Poulenc decided to turn the play into an opera thirty years later, he had to assess the telephone’s place in current 1950s society. Poulenc knew all about the nature of fear, depression and nervous exhaustion, obsession and rejection the loss of a lover can engender. “I’m writing an opera,” he disclosed to a friend, “you know what it’s about: a woman (me) is making a last telephone call to her lover who is getting married the next day.” Poulenc had recently lost one lover and was enduring an enforced separation from another whom, he felt sure, “life will inevitably take away from me in one way or another.” Poulenc was ready to reexamine the anxiety of technological dehumanization.

In the end, he composed a score that emotionally spoke to the audience while at the same time retained the substance of the play. Above all, the score had to portray the pain of the heroine so that the audience would be able to sympathize with Elle’s emotions. As such, the orchestra is taking the role of the ex-lover, communicating what is said on the other end of the line.

In the end, he composed a score that emotionally spoke to the audience while at the same time retained the substance of the play. Above all, the score had to portray the pain of the heroine so that the audience would be able to sympathize with Elle’s emotions. As such, the orchestra is taking the role of the ex-lover, communicating what is said on the other end of the line. With the telephone the only link to her lover, Elle’s anxiety is portrayed through her responses and reactions to calls from wrong numbers while waiting for her lover to call. She is clearly exhibiting all the symptoms of a nervous breakdown, including anxiety, depression, hallucinations, and attempted suicide brought on by “technostress.” That general mental imbalance and suffering is not the result of the end of a relationship, however, but comes from her chronic use and dependence on technology. She even admits sleeping with the telephone! Elle finally comes to the realization that it is the technology she is so dependent on, that actually keeps them apart; the loneliness in her life is filled with technology, thus making it a weapon in the end. The final moment of Elle’s “technostress” occurs at the end of the opera, when she wraps the phone cord around her neck. As she cuts off her breathing and commits suicide, she utters her final declarations of love. “La Voix humaine is a curious, uncomfortable work which does not fit securely within the traditional boundaries of opera or play.” For those able to appreciate its subtleties, it is a work of genius, revealing naked emotions rarely exhibited on the stage with such realism. Just goes to show, communications technology has certainly changed, but the way it can engender psychological problems seems rather timeless!

Francis Poulenc: La Voix Humaine