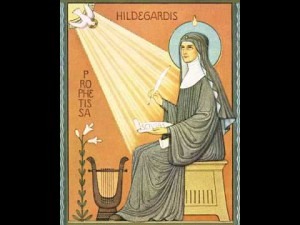

She experienced “shades of the living light” at age three, and understood that she was experiencing visions by the age of five. Her parents, a family of the free lower nobility, had absolutely no idea how to deal with the unusual gifts of their daughter. And since the 12th century had barely dawned, they decided to offer Hildegard to the church. Hildegard was enclosed—a slightly more polite way of saying locked away—at the nunnery at Disibodenberg in the Palatinate Forest. She was taught to read and write, and eventually learned to play the ten-stringed psaltery. The study of musical notation did not present a significant challenge, and the young nun secretly dabbled in compositions. However, only when Hildegard reached the age of 42 did she receive a clear vision from God instructing her to “write down that which you see and hear.” And writing she did!

She experienced “shades of the living light” at age three, and understood that she was experiencing visions by the age of five. Her parents, a family of the free lower nobility, had absolutely no idea how to deal with the unusual gifts of their daughter. And since the 12th century had barely dawned, they decided to offer Hildegard to the church. Hildegard was enclosed—a slightly more polite way of saying locked away—at the nunnery at Disibodenberg in the Palatinate Forest. She was taught to read and write, and eventually learned to play the ten-stringed psaltery. The study of musical notation did not present a significant challenge, and the young nun secretly dabbled in compositions. However, only when Hildegard reached the age of 42 did she receive a clear vision from God instructing her to “write down that which you see and hear.” And writing she did!

Significantly, Hildegard penned three great volumes of visionary theology, in which she detailed and analyzed her visions. It offers one of the earliest accounts of purgatory, and her “descriptions of the possible punishments are often gruesome and grotesque, emphasizing the work’s moral and pastoral purpose.” Her nearly 400 letters address correspondents ranging from Popes to Emperors, and include many sermons and gospel commentaries. And did I mention that she wrote two extended biographies of saints and ecclesiastical leaders? Most significantly, however, are two enormous volumes on natural medicine and cures. The nine books of Physica focus on the scientific and medicinal properties of plants and animals, while the Causae et Curae is an exploration of the human body and its connections to the rest of the world. Supposedly, Hildegard was the first person to identify the importance of boiling drinking water to prevent disease. And in her spare time, she even invented her own alternative alphabet!

Hildegard of Bingen: Ordo virtutum (Excerpts)

But it is primarily Hildegard’s music that has received much popular interest in recent years. One of the largest extant musical outputs among medieval composers, Hildegard wrote a substantial number of liturgical songs to her own texts. Highly melismatic and featuring recurrent melodic units, her soaring melodies push the accepted boundaries of 12th century Gregorian chant. It has even been suggested that Hildegard sought a close association between music and the female body, “giving voice to the anatomy of female desire.” Her best know composition is the morality play Ordo Virtutum (Play of the Virtues). Composed around 1151, the play presents a protagonist representing the human soul. 16 virtues, essentially personifications of various moral attributes, attempt to persuade the soul to choose a godly life. And there is even one speaking role for the Devil! Hildegard was given approval from Pope Eugenus in 1148 to document her visions, but the Vatican did not officially canonize her until 2012. If you are a polymath genius and a woman, no surprises there!

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Regina Susanna Bach (1742-1809) Learn about Bach's youngest surviving child - Bach Babies in Music

Johanna Carolina Bach (1737-81) Discover how family and crisis intersected in Bach's world - Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) From Soho to the royal court: Johann Christian Bach's London success story - A Tour of Boston, 1924

Vernon Duke’s Homage to Boston Listen to pianist Scott Dunn bring this musical postcard to life