Henriëtte Bosmans has one of the most fascinating biographies in twentieth-century music history. She was a celebrated piano soloist and composer. Her love for great women performers inspired deeply beautiful works for both cello and voice. And when the Nazis invaded her homeland, the course of her life and her career was changed forever.

Today we’re looking at the life, loves, and legacy of Dutch pianist and composer Henriëtte Bosmans.

Childhood and Student Days

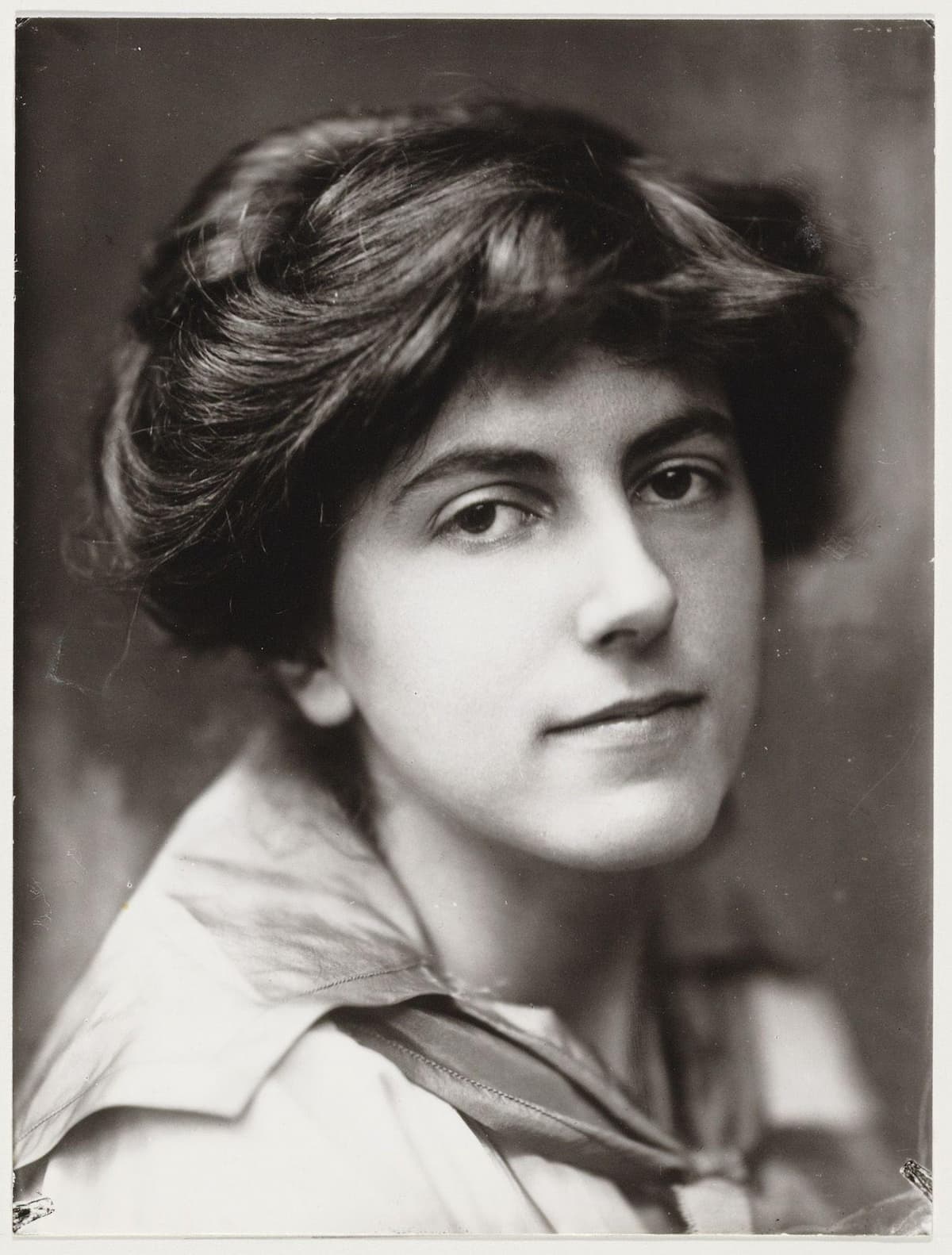

Photo of Henriëtte Bosmans by Jacob Merkelbach, 1917

Henriëtte Bosmans was born in December 1895 in Amsterdam.

Her father Henri was the principal cellist of the newly established Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, and her mother Sarah Benedicts was a Jewish piano teacher.

Tragically, Henri died when Bosmans was just a baby, leaving Sarah a single mother.

To support herself and her musically talented daughter, Sarah taught at the Amsterdam Conservatory, a job she held for forty years. This meant that growing up, Bosmans had access to some of the best Dutch music teachers of the era.

When she was in her teens, Bosmans followed in her mother’s footsteps and began to teach. The earliest compositions we have of hers date from this time.

Her first big appearance as a pianist came when she was nineteen years old, in Utrecht, Holland. It was the first of many triumphs.

She pursued a career as a concert pianist throughout the 1920s, appearing as a soloist across Europe with famous conductors like Mengelberg and Monteux. She also kept composing.

Henriëtte Bosmans: Piano Concertino

Relationship With Frieda Belinfante

Henriëtte Bosmans and Frieda Belinfante

In 1920 Bosmans met a cellist nine years her junior named Frieda Belinfante.

According to Belinfante, their relationship began after Belinfante discovered that Bosmans’s male lover was cheating on her and pressuring her to have an abortion. Belinfante, always a mother hen type, moved in with Bosmans to help protect her during a vulnerable time.

The two developed a deep connection. Belinfante would later remember, “I was a high admirer of this wonderful, beautiful looking girl, composer.”

Bosmans was famously disorganized and hopeless at accomplishing day-to-day tasks, absorbed as she was by performing and composing. So Belinfante helped keep the household running, leading Bosmans to nickname her “Mommy and Pops.”

In return, Belinfante inspired some of Bosmans’s most beautiful works for cello, including her astonishing cello sonata.

Henriëtte Bosmans: Sonata for cello and piano

The partnership between the two women lasted for seven years. They drifted apart after Belinfante was pressured into marriage by her future husband, a flutist who she’d ultimately divorce.

Bosmans’s two best-known works from this era are probably her Concertino for Piano and Orchestra, dating from 1928, and a concert piece for flute from 1929 (interestingly, dedicated to Belinfante’s husband). The latter piece won her second prize in the Concertgebouw Prize Competition.

Henriëtte Bosmans: Concert Piece for Flute and Chamber Orchestra

War and Tragedy

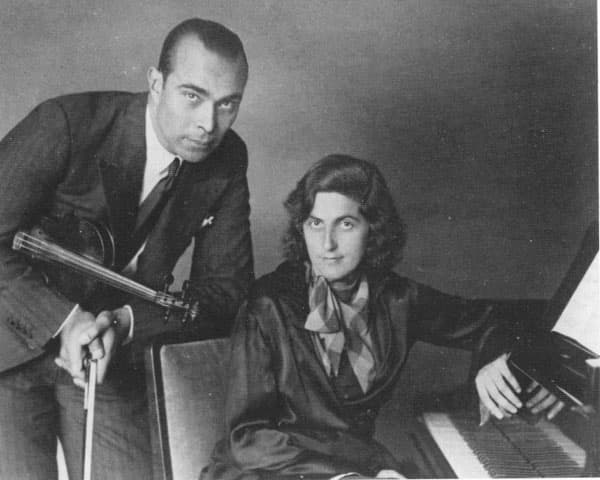

Francis Koene and Henriëtte Bosmans, 1922

A tragic love story unfolded for Bosmans in the 1930s when she fell in love with violinist Francis Koene. The couple became engaged in 1934, but he died of a brain tumor in January 1934 before they were able to be married.

Between her grief at losing her fiancé and the threat posed by the Nazis later in the decade, she entered a creatively fallow period.

Throughout the 1930s, conditions in Europe deteriorated. After the invasion of the Netherlands in the spring of 1940, the Nazis required Dutch musicians to join the Kultuurkamer, an organization devoted to advancing Nazi ideology through art. Bosmans, however, refused. It was a dangerous position for a half-Jewish woman to take, and economically disastrous. Performances of her work were banned in August 1942.

In addition, despite the fact that her elderly Jewish mother had married a Catholic man, and that some Nazi officials believed such spouses should be immune from deportation, her elderly mother was arrested and sent to Westerbork. Luckily through Bosmans’ desperate advocacy, and the help of star conductor Willem Mengelberg, her mother’s life was spared. It’s very possible that without the clout that her daughter’s musical career offered, Sarah Bosmans would have died in the Holocaust.

Desperate to play and hear music, Bosmans performed at a variety of underground house concerts, which inevitably turned into deeply emotional and dangerous affairs. During one close call, a concert was raided. She escaped through the backyard, but the audience was fined.

Postwar Life

Bosmans enjoyed a creative renaissance after the war ended. She began a fruitful association with soprano Noémie Pérugia. The two women began performing as a vocal and piano duo. Their relationship inspired twenty-five vocal works that Bosmans wrote between 1948 and 1951.

Henriëtte Bosmans: Lead, Kindly Light

Sadly, Bosmans’s health declined in the early 1950s. She was initially misdiagnosed with ulcers, but eventually doctors realized she had terminal stomach cancer.

Bosmans and Pérugia gave their final performance together in April 1952. Bosmans collapsed immediately afterward. She died nine weeks later at the age of 56.

Happily, more and more attention is being paid to her and her extraordinary work, especially with growing interest in the work of women and LGBTQ+ composers. Her legacy endures to this day, especially in Holland, where in 1994, the Society of Dutch Composers began offering the $3500 Henriëtte Bosmans Prize to support young up-and-coming Dutch composers.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter