Controversy frequently surrounded Gustav Klimt‘s paintings, but he was not a rebellious individual. He did cultivate a certain coarseness of manner primarily as a defense against unwanted curiosity, and he went to considerable lengths to protect his inner world from any kind of scrutiny. When he was asked to expand on his values and ideas, he quickly insisted that he was not an interesting person and had nothing of value to contribute.

Alexander Zemlinsky: String Quartet No. 1 in A Major, Op. 4

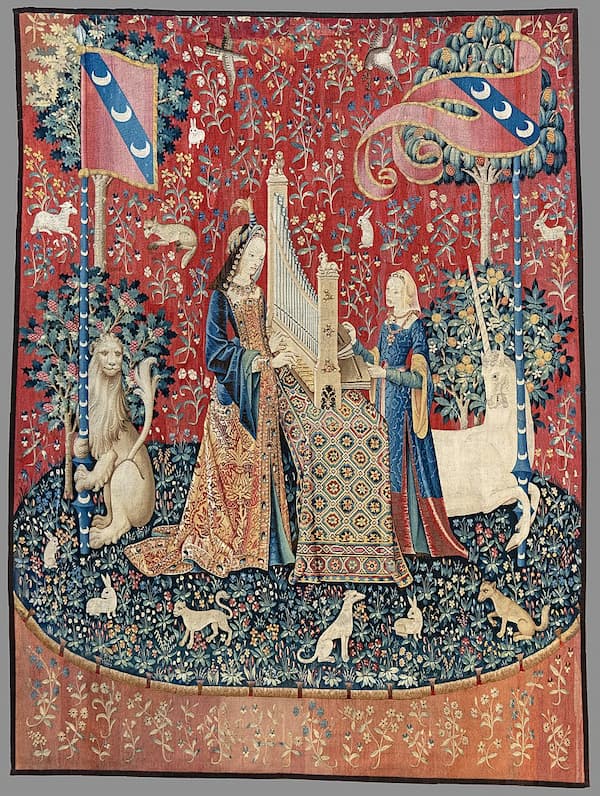

Personality

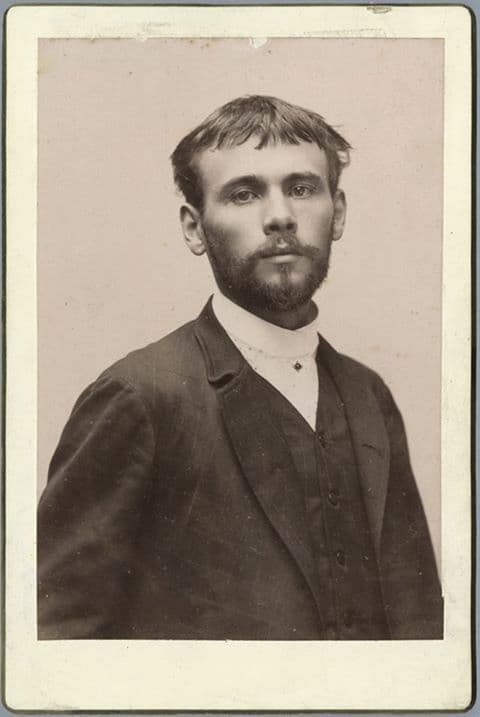

Gustav Klimt in 1887

As he once explained, “I can paint and draw. I believe as much myself, and others also say they believe it. But I am not sure that it is true. Two things only are certain: I have never painted a self-portrait. I am less interested in myself as a subject for a painting than I am in other people, above all women. I am not particularly interesting as a person. There is nothing special about me. I am a painter who paints day after day from morning until night.”

And he continued, “I have the gift of neither the spoken nor the written word, especially if I have to say something about myself or my work. Even when I have a simple letter to write, I am filled with fear and trembling as though on the verge of being seasick. And this should not be regretted. Whoever wants to know something about me, as an artist, the only notable thing, ought to look carefully at my pictures and try to see in them what I am and what I want to do.”

Richard Strauss: Four Last Songs, “Im Abendrot”

Childhood

Gustav Klimt’s birthhouse

Gustav Klimt was born on 14 July 1862 in Baumgarten, then a rural suburb of Vienna. He was the second of seven children and came from a lower middle-class family of Moravian origin. His father, Ernst Klimt, was a goldsmith and engraver who had moved to Vienna to improve his financial position. He met and married Anna Finster, who held the unfulfilled ambition of becoming an opera singer. Anna and her daughter Klara suffered from some kind of mental illness, and Gustav lived in great fear for most of his life of succumbing to hereditary madness.

The Klimt sons displayed artistic talent early on, with Ernst being a painter and Georg a very talented sculptor, engraver and designer. In fact, he would later produce many of the original frames for Klimt’s paintings. The only real source of information about Klimt’s childhood comes from the memoires of his sister Hermine. As she writes, “he liked animals and could be very noisy at times, and he certainly liked to eat dumplings.” The Klimt family essentially lived in horrendous poverty, and they were frequently evicted for failing to pay rent. Klimt’s first steps towards becoming an artist were determined by the need to find a secure job as quickly as possible.

Johannes Brahms: Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115 “Allegro”

Initial Studies

Ernst Klimt

One of his teachers in secondary school advised Gustav’s father to arrange for his son’s talent for drawing to be developed. As such, Gustav applied to the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule, a school of applied arts and crafts, and he studied architectural painting from 1876 until 1883. A biographer writes, “Klimt was an excellent student. The drawings from life and from plaster casts of Classical sculpture that he produced at the school, and the portraits he made mostly from photographs, reveal a high and precocious degree of technical mastery.”

All three Klimt brothers studied at the same school and, together with another student and close friend, Franz Matsch, began to be offered commissions. The “Company of Artists,” as they called themselves, carried out decorations for the museum housing the imperial art collection in Vienna. A year later, they collaborated on decorative paintings for a private house in Vienna. Not to be outdone, they worked together on a ceiling painting for the Kurhaus in Carlsbad.

Arnold Schoenberg: Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19

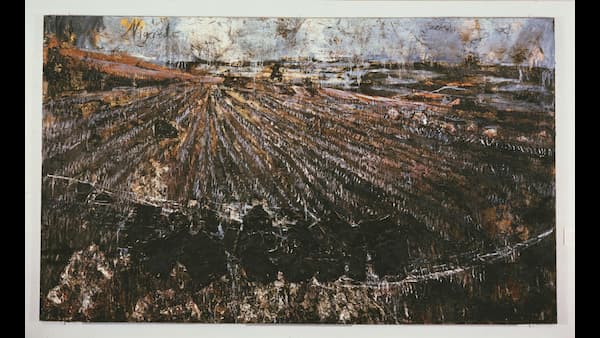

From Tradition to Innovation

Gustav Klimt’s Theatre of Shakespeare – Ceiling painting in the Burgtheater in Vienna, 1886

Klimt greatly admired Hans Makart, the so-called Painter-Prince, who had a limitless appetite for vast canvases of imagined or imaginary historical events. His huge pictures, some of them nine meters long, turned the historical events they depicted into grand opera, and Makart himself knew how to produce himself. “He loved to dress up, worked in a vast studio decorated like a stage set and preferred to paint in the presence of visitors.”

Gustav Klimt’s ceiling painting

Even before graduation, Klimt received some lucrative commissions, but he was not interested in novelty or extending boundaries. As a critic writes, “he simply wanted to excel at what was commonly regarded at the time as significant art.” Klimt was awarded the Emperor’s Prize and he was on the verge of having a fabulous career as a classicist painter when he began turning towards the radical new styles of the Art Nouveau. And a visit to Ravenna in 1903 brought him in contact with Byzantine mosaics, which in turn, sparked a creative explosion, his so-called “Golden Period.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter