“It is always fatal to have music or poetry interrupted”

George Eliot

During her lifetime, she was as famous as Charles Dickens. Her novels, which appeared in rapid succession from 1859, held Victorian readership spellbound for decades. Most of her fiction dealt with simple people and rural life in provincial England in the first half of the 19th century. And that’s hardly surprising as she was born on 22 November 1819—200 years ago—in Warwickshire, Central England. But George Eliot was not born George Eliot but Mary Ann Evans, daughter of a respected estate manager. Mary Ann, sometimes shorted to “Marian” was a voracious reader and privately educated, and her first major literary works where English translations of German agnostic theological writings. She had working knowledge of five ancient and modern languages, and after travelling to Switzerland she eventually move to London intent on becoming a writer. She became assistant editor of the left-wing Westminster Review, and she contributed various essays and reviews under the name Marian Evans. It has been suggested “woman writers were common at the time, but Evan’s role as a female editor of a literary magazine was quite unusual.” Evans, however, decided to become a novelist.

Harold Meltzer: 2 Songs from Silas Marner

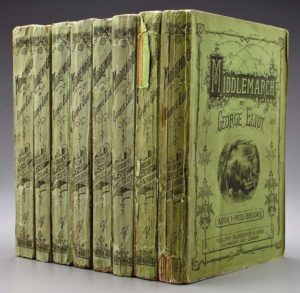

First edition of Middlemarch

There are various reasons why Mary Ann Evans decided to adopt the nom-de-plume George Eliot. For one, she was in a relationship with fellow writer George Henry Lewes. He was trapped in a marriage to a wife who had had been the lover of another man and even had children by him. But it was Eliot “who truly scandalized society when she decided to openly cohabit with the still-married Lewes.” Within the strict moral code of the Victorian Era sexual propriety was represented by prudery and repression. And while premarital sex was an absolute no-no in the upper and middle classes—except between men and servants or prostitutes—the purity of women was strictly enforced. To have an open relationship with a married man meant being socially ostracized, and Eliot was unable to see female friends without tarring their reputations by association. But she also had a professional reason for changing her name. In a published essay she criticized the trivial and ridiculous plots of contemporary fiction written by women. To be taken seriously as a writer, she needed a male name. As she explained to her biographer, “George was Lewes’s forename, and Eliot was a good mouth-filling, easily pronounced word.”

Literary critics have suggested that “the period in Eliot’s life, when she was a social outcast, became her most productive.” Her first complete novel Adam Bede was published in 1859, and within a year of completing she finished The Mill on the Floss. Silas Marner appeared in 1861 and Romolo in 1863, followed by Felix Holt and her most acclaimed novel Middlemarch. Her last novel Daniel Deronda was published in 1876, and everything she published was instantly successful. And although her private life shocked many of her readers, it never affected her popularity as a novelist. Queen Victoria became a fan, as did Emily Dickinson, and Lewis and Eliot were finally accepted into polite society in 1877 when they were introduced to Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria. Eliot went on to cause a second public scandal when, after the death of Lewes, she married her financial advisor John Walter Cross, twenty years her junior. In a fit of depression, Cross jumped from the hotel balcony into the Grand Canal in Venice during their honeymoon. Although he survived, his desperate jump has predictably given rise to all kinds of Freudian theories.

Literary critics have suggested that “the period in Eliot’s life, when she was a social outcast, became her most productive.” Her first complete novel Adam Bede was published in 1859, and within a year of completing she finished The Mill on the Floss. Silas Marner appeared in 1861 and Romolo in 1863, followed by Felix Holt and her most acclaimed novel Middlemarch. Her last novel Daniel Deronda was published in 1876, and everything she published was instantly successful. And although her private life shocked many of her readers, it never affected her popularity as a novelist. Queen Victoria became a fan, as did Emily Dickinson, and Lewis and Eliot were finally accepted into polite society in 1877 when they were introduced to Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria. Eliot went on to cause a second public scandal when, after the death of Lewes, she married her financial advisor John Walter Cross, twenty years her junior. In a fit of depression, Cross jumped from the hotel balcony into the Grand Canal in Venice during their honeymoon. Although he survived, his desperate jump has predictably given rise to all kinds of Freudian theories.

Margaret Ruthven Lang: Ojala (God Willing)

Eliot transformed herself from a country girl into one of the leading urban intellectuals of her time. And there can be no doubt that her novels represent her single greatest professional achievement. Her use of music as indicators of moral nature or emotional susceptibility in her writings has been insightfully explored. For Eliot, “music that stirs all one’s devout emotions blends everything into harmony, makes one feel part of one whole, which one loves all alike, losing the sense of a separate self.” Unlike Jane Austen, Eliot does not always identify specific compositions, but she is very specific about the nature of the music. She once stated, “painting and sculpture are but an idealizing of our actual existence. Music arches over this existence…” In her novels Eliot subtly reveals the relationship between feeling and auditory sensibility. As one literary scholar puts it, “the significance of music had grown with her own growth, which is how, in the novels, it became integral to the idea of moral development.” It might be said that Eliot’s entire life was an act of becoming in response to restrictions placed on feminine ambition circumscribed by gender. “The greatest benefit we owe to the artist,” she once wrote, “is the extension of our sympathies.”

Evan Mack: Preach Sister, Preach, No. 4 George Eliot