Some marriages do end up in divorce court, but very few divorces become prescribed case studies during the first year of law studies. But that is exactly what happened when Frederica von Stade—described as one of America’s finest artists and singers—filed for divorce from Peter Elkus. When the couple married on 9 February 1973, “Fricka,” as she is known to family, friends and fans, stood at the very beginning of her career, performing minor roles with the Metropolitan Opera Company. By the time their marriage was dissolved in 1990, Fricka’s career had succeeded dramatically, and she had accumulated substantial wealth. The question before the courts became important in the development of American family law. It had to decide if Frederica’s celebrity status and any income derived from it constituted marital property subject to equitable distribution.

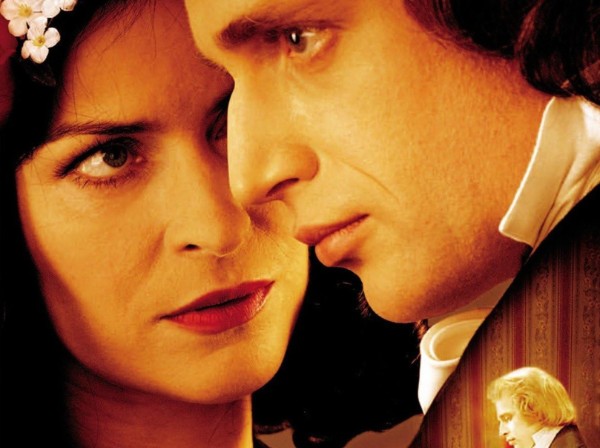

Frederica von Stade as Cherubino

Born into a prominent New Jersey family, von Stade dreamt of becoming a Broadway star, and despite not being able to read music, auditioned for the Mannes School of Music. She quickly became a full-time student and was accepted into the class of Sebastian Engelberg. Peter Elkus, bass-baritone, photographer and later singing coach, was also associated with Mannes, and when Engelberg died in 1979, he was asked to fill the vacancy. Fricka auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera in 1969 and was immediately offered a three-year contract. She made her debut in 1970 and, within a couple of years, was singing with the San Francisco Opera, Glyndebourne Festival Opera and Paris Opera, and from 1974 to 1976 at the Salzburg Festival.

Frederica von Stade

Jules Massenet: Cendrillon, Act III: Enfin, je suis ici (Frederica von Stade, mezzo-soprano; London Philharmonic Orchestra; John Pritchard, cond.)

Elkus and von Stade married in Paris in 1973, and her career skyrocketed. She appeared on all stages of the world’s greatest opera houses and concert halls, and von Stade made more than a hundred recordings, including symphonic works, sacred music, operas, musicals, art songs, pop songs, folk songs, jazz and comedy. She has been nominated for a Grammy for best classical vocalist nine times, and numerous high-profile prizes have honoured her recordings. Elkus travelled with Fricka throughout the world, attending and critiquing her performances and rehearsals. He photographed her for album covers and magazine articles, and he was her voice coach and teacher for 10 years between 1975-1985. During divorce proceedings, von Stade said, “It’s the same old story. You can’t learn to drive from your husband. A husband-and-wife team is a risky thing, … We thought we were strong enough to defy it, and we weren’t.”

Richard Strauss: “Begegnung” TrV 98 (Frederica von Stade, mezzo-soprano; Martin Katz, piano)

Peter Elkus

Elkus and von Stade did agree to share custody of their children, but they could not negotiate a mutually satisfactory division of their wealth. Her success was obviously founded on the qualities of her voice, but Elkus argued that he had given up his own work as a singer to support her career. He suggested he “had guided her through the thickets of an expanding repertory and a demanding worldwide schedule.” It entitled him, so it was argued, not just to a share of the marital wealth but also to a payment based on the money she would make in the coming years from performing and celebrity endorsements. Her lawyers argued that his coaching had sometimes done her voice more harm than good and that there were no endorsement prospects. As such, he asked the Supreme Court of New York County to rule that her career and profile belonged to her and her alone.

Frederica von Stade in Rossini’s “Cenerentola”

The judge agreed and noted that “Elkus’ self-sacrifice in supporting her endeavors had been compensated by a substantial lifestyle in which he had reaped the rewards of his association with her and that his services to her would be adequately remunerated by his share of the couple’s tangible assets.” That particular verdict was appealed, with Elkus contending that since Frederica’s career and celebrity status increased in value during the marriage due in part to his contributions, “he was entitled to equitable distribution of all present and future marital property.”

Frederica von Stade at the Met

The Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York agreed and overturned the trial court’s order in a unanimous judgment. Frederica’s celebrity status was considered the same as that of a licensed professional and subject to equitable distribution. It essentially meant that Elkus was effectively a shareholder in von Stade’s future. The reason this ruling is still taught in law school is that it establishes the principle that “when the marriages of performing artists are dissolved, the courts can attribute an economic value to their celebrity status and treat it as marital property to be shared with their former spouses.” That particular ruling has been very popular in Hollywood, and it certainly informed the settlement in the case of Heather Mills vs. Paul McCartney.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Claude Debussy: “Ariettes oubliees” (Frederica von Stade, mezzo-soprano; Martin Katz, piano)