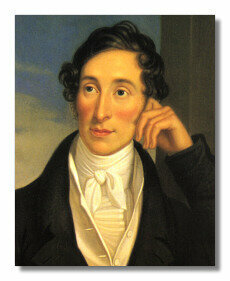

Carl Maria von Weber

Credit: http://www.classical.net/

The comparatively late addition of the clarinet family to our modern catalogue of musical instruments at the turn of the 18th-century immediately spawned countless generations of woodwind virtuosi. Concordant with the rise of the woodwind virtuosi, the instrument underwent a series of developments in key construction, expanding the six-key layout to ten. This allowed for greater agility and flexibility in the performance of chromatic scales and passages. But there were also developments regarding embouchure. Anton Stadler, who inspired Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to produce some of his most memorable compositions, for example, played the reed on his top lip. This custom gradually changed, and by the beginning of the 19th century it had become common practice to play the reed on the bottom lip. One of the first proponents of this new style of playing was Heinrich Baermann, who was capable of producing an expressive and luxurious tone, and “great dynamic range.” It is hardly surprising that a number of composers, among them Franz Danzi, Peter von Lindpaintner, Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer crafted compositions that explored Bearmann’s exceptional abilities. However, it was Carl Maria von Weber who most famously exploited Baermann’s “welcome homogeneity from top to bottom of the register” in no fewer than five large-scale works.

Heinrich Baermann was widely considered the “Rubini of the clarinet” because he rivaled the great Italian tenor in richness, beauty, and phenomenal compass. He was born in Potsdam, in 1784, and quickly showed sufficient aptitude towards music to be sent to a military music school. He was soon engaged by Prince Louis Ferdinand of Berlin as a bandsman in the Prussian Life Guards, yet simultaneously allowed to establish a highly successful career as a traveling virtuoso, entertaining audiences throughout Europe and Russia. Since he was still a military man, however, he had to participate in the Battle of Jena in 1806 and was promptly captured by Napoleonic troops. Imprisoned for an entire year, Baermann had to endure an exceptionally harsh winter. Upon his release, he quickly left the military and obtained an appointment at the court orchestra of Munich, a position he held until his retirement in 1834.

Heinrich Baermann was widely considered the “Rubini of the clarinet” because he rivaled the great Italian tenor in richness, beauty, and phenomenal compass. He was born in Potsdam, in 1784, and quickly showed sufficient aptitude towards music to be sent to a military music school. He was soon engaged by Prince Louis Ferdinand of Berlin as a bandsman in the Prussian Life Guards, yet simultaneously allowed to establish a highly successful career as a traveling virtuoso, entertaining audiences throughout Europe and Russia. Since he was still a military man, however, he had to participate in the Battle of Jena in 1806 and was promptly captured by Napoleonic troops. Imprisoned for an entire year, Baermann had to endure an exceptionally harsh winter. Upon his release, he quickly left the military and obtained an appointment at the court orchestra of Munich, a position he held until his retirement in 1834. Carl Maria von Weber first met Heinrich Baermann in Darmstadt, in 1811. At that time, Baermann was already a mature virtuoso who played with great exuberance and personal charisma. His innovative playing style described as a “mixture of French vivacity and German fullness with darker tone” immediately appealed to Weber. Performer and composer became close friends and embarked on a number of artistic collaborations, including the Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73. This concerto played a critical role in Weber’s career, establishing his compositional acumen long before he made his name as an opera composer. Weber’s musical language relies on melodies colored by an increasingly sophisticated and chromatic language in the orchestra. This emphasis on orchestral color, achieved through deliberate prominence of the inner voices of the musical texture not only highlighted a groundbreaking and pioneering handling of the orchestral forces, it greatly enhanced and accentuated the overall dramatic expression as well. The individuality of his orchestral sound world uniquely combined with the dramatic and technical passages assigned to the clarinet. These qualities, admired by Berlioz, Wagner, and Mahler, instantly emerge in the restlessness of the opening movement, as well as in the exquisite clarinet and horn dialogue in the slow “Adagio.” The concluding “Rondo,” not surprisingly, was designed to showcase Baermann’s unique abilities and to explore the technical innovations of the instrument. Carl Maria von Weber wrote the first movement of the concerto, including all orchestral parts, in a single day! Carl Baermann — Heinrich’s son and successor to his position of principal clarinetist at the Munich Orchestra who also authored a leading method for teaching the clarinet entitled Complete School for the Clarinet — felt that the opening movement was in need of improvement. Specifically, he thought that the transition from the playful opening section to the solemn second theme area needed something a bit more exciting. As such, he inserted a brilliant solo passage, which quickly became a standard feature in one of the most popular and frequently performed works for clarinet and orchestra.

The Concerto will be performed at the French May.