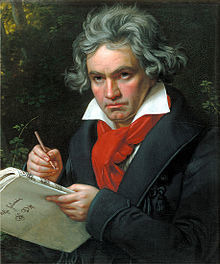

The musical genius of Beethoven, though witnessed over 200 years ago, is still deeply admired by many because Ludwig van Beethoven once described his talent saying, “I keep a thought in my mind for a very long time. I am certain that my memory is reliable, as I never forget, even tunes from years ago… The only part really left to do is writing it out, which can be completed very quickly. I sometimes do other works at the same time, but I never mix them up.” This goes on to show that long before Beethoven became completely deaf, he was already adept at storing music in his brain. Yet, it is still baffling how one could possibly complete his greatest masterpiece like the Ninth Symphony in complete deafness.

The musical genius of Beethoven, though witnessed over 200 years ago, is still deeply admired by many because Ludwig van Beethoven once described his talent saying, “I keep a thought in my mind for a very long time. I am certain that my memory is reliable, as I never forget, even tunes from years ago… The only part really left to do is writing it out, which can be completed very quickly. I sometimes do other works at the same time, but I never mix them up.” This goes on to show that long before Beethoven became completely deaf, he was already adept at storing music in his brain. Yet, it is still baffling how one could possibly complete his greatest masterpiece like the Ninth Symphony in complete deafness.

Josef Hofmann, another genius of his time, was considered a poor sight reader. Yet he displayed an incredible memory—in 21 consecutive concerts in St. Petersburg, he performed 225 different works from memory without repeating a single piece. In his wife’s diary, it was recorded that he openly performed Brahms’ Handel Variations based on his memory, after watching the song played on a program two and a half years ago. Compared to the genius of Liszt and Saint-Saën, he could listen to a musical piece once and play it correctly from memory without seeing the printed notes. As good friends, Hofmann would visit Leopold Godowsky, the famed Polish-American composer, while he composed “Fledermaus” at the studio. A week later, Hofmann visited Godowsky again and played the entire transcription by heart. It turns out the piece had not even yet been written down. “Fledermaus” is regarded by Schonberg as one of the most complicated stunts ever written for piano.

Josef Hofmann, another genius of his time, was considered a poor sight reader. Yet he displayed an incredible memory—in 21 consecutive concerts in St. Petersburg, he performed 225 different works from memory without repeating a single piece. In his wife’s diary, it was recorded that he openly performed Brahms’ Handel Variations based on his memory, after watching the song played on a program two and a half years ago. Compared to the genius of Liszt and Saint-Saën, he could listen to a musical piece once and play it correctly from memory without seeing the printed notes. As good friends, Hofmann would visit Leopold Godowsky, the famed Polish-American composer, while he composed “Fledermaus” at the studio. A week later, Hofmann visited Godowsky again and played the entire transcription by heart. It turns out the piece had not even yet been written down. “Fledermaus” is regarded by Schonberg as one of the most complicated stunts ever written for piano.

While the musical genius of Beethoven and Hofmann are clearly recognized, it isn’t always the case that an incredible memory is necessarily the product of incredible intellect. Kim Peek is a good example. Better known as the inspiration for the character Raymond Babbitt in the movie Rain Man, Peek suffered developmental disabilities due to congenital brain abnormalities. He had difficulties performing ordinary motor skills, such as buttoning up his shirt or walking, and only scored 87 on IQ tests. However, he possessed the ability to store information and music in his long-term memory just after one look at the material. A brain scan showed that he possessed a photographic memory, and it is believed he could recall the content of at least 12,000 books.

While the musical genius of Beethoven and Hofmann are clearly recognized, it isn’t always the case that an incredible memory is necessarily the product of incredible intellect. Kim Peek is a good example. Better known as the inspiration for the character Raymond Babbitt in the movie Rain Man, Peek suffered developmental disabilities due to congenital brain abnormalities. He had difficulties performing ordinary motor skills, such as buttoning up his shirt or walking, and only scored 87 on IQ tests. However, he possessed the ability to store information and music in his long-term memory just after one look at the material. A brain scan showed that he possessed a photographic memory, and it is believed he could recall the content of at least 12,000 books.

Peek would normally spend about an hour to read a book, and would thereafter recall vast amounts of information in subjects ranging from history, to sports and to music and dates. His reading technique involved reading two pages simultaneously—the left with his left eye and the right with his right—at a rate of about 8–10 seconds per page.

Although never recognized as a musical prodigy, Peek’s musical abilities gained widespread attention when he began studying the piano. He could apparently remember tunes played decades before, and could recite them on the piano as allowed by his limited physical condition. He could give a running commentary as he played, could identify almost any instrument in the orchestra, and could correctly guess the composer of a piece of music by comparing the work to the thousands of samples recorded in his memory.

How do the neurons in a musician’s brain function? How are these seemingly super-brain powers created? If we knew, we could then perhaps understand how Hofmann and Peek could recall and perform music just after one hearing, how Beethoven could still compose masterpieces in deafness, or the way Handel could still perform at international standards despite complete blindness.

In fact, music has appeared to improve memory in several situations. In a study of the effects of music on memory, visual cues were showed to research participants with music played in the background. Later, participants were asked to recall the details of the visual cues. When it appeared that the details had been forgotten, participants were presented with the background music, and were then shown to recover the information.

Other studies show that musical training also enhances memory for text. Words remembered as lyrics to a song are remembered significantly better than when presented solely by speech. Training in music has also shown to improve verbal memory in children and adults. Musically-trained participants have proven to perform better than non-musically trained participants in immediate recall for words in another study. As supported by previous research, the authors suggested that musical training leads to neuroanatomical changes in the left temporal lobe, which is responsible for verbal memory, thereby enhancing verbal memory processing. MRI has shown that this part of the brain is larger in musicians than non-musicians.

Although the study of music’s impact on the brain is a complex neuroscience with many areas still waiting to be investigated, it is without question that the findings only continue to reaffirm us of how simple and yet so complex the human brain is. It is a funny thought to think that there are as many neurons in the brain as there are stars in the Milky Way. Furthermore, if music alone can show how capable the human brain has developed to be, imagine how much more we can achieve with all the other functions of this mysterious three-pound mass of grey and white matter that ultimately determines who we are.

References: Josef Hofmann, Kim Peek, Elisabeth Platel

Photo credits: upload.wikimedia.org, wikimedia.org, death-watch.com

More Sciences

-

Music as Medicine: How Sound Affects Our Mental Health Find out what neurologists have discovered about your playlist!

Music as Medicine: How Sound Affects Our Mental Health Find out what neurologists have discovered about your playlist! -

Conquering Stage Fright – Scientific Methods to Overcome Performance Anxiety Learn how to use simple cognitive reframing to transform performance anxiety

Conquering Stage Fright – Scientific Methods to Overcome Performance Anxiety Learn how to use simple cognitive reframing to transform performance anxiety -

Mental Training for Musicians – Unlocking Peak Performance Your mind might be the most important instrument you own!

Mental Training for Musicians – Unlocking Peak Performance Your mind might be the most important instrument you own! -

Once More, With Feeling: Music, Dopamine, and the Brain Why can you listen to your favorite song on repeat without getting tired of it?

Once More, With Feeling: Music, Dopamine, and the Brain Why can you listen to your favorite song on repeat without getting tired of it?