The unprecedented suffering inflicted by the relentless and ruthless personality cult of Chairman Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution had a devastating effect on society and on music. Within China’s cultural and intellectual fabric Beethoven had become synonymous with everything the nation aspired to be. “He was the guiding spirit for young men and women, driven by a love of their country, who were determined to seize fate by the throat and build a China of social equality and dignity.” Under Mao’s dictatorship, listening to the music of Beethoven now became a political crime. The Chairman proudly proclaimed, “All literature and art belongs to definite classes and are geared to definite political lines. There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake.” The former actress Jiang Qing, better known as Mao Zedong’s wife, was declared a patron of culture. And Madam Mao launched a vicious campaign to cleanse the arts, and all plays, films, operas, ballets and music considered “feudalistic and bourgeois” were banned. Art had become a political tool with catastrophic consequences for musicians and educators in China.

The unprecedented suffering inflicted by the relentless and ruthless personality cult of Chairman Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution had a devastating effect on society and on music. Within China’s cultural and intellectual fabric Beethoven had become synonymous with everything the nation aspired to be. “He was the guiding spirit for young men and women, driven by a love of their country, who were determined to seize fate by the throat and build a China of social equality and dignity.” Under Mao’s dictatorship, listening to the music of Beethoven now became a political crime. The Chairman proudly proclaimed, “All literature and art belongs to definite classes and are geared to definite political lines. There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake.” The former actress Jiang Qing, better known as Mao Zedong’s wife, was declared a patron of culture. And Madam Mao launched a vicious campaign to cleanse the arts, and all plays, films, operas, ballets and music considered “feudalistic and bourgeois” were banned. Art had become a political tool with catastrophic consequences for musicians and educators in China.

It was actually the music of Claude Debussy that was initially targeted for ideological slander. Highest levels of government considered his music “the dirt left behind by western imperialism.” And when the composer and educator He Luting, president of the Shanghai Conservatory came to the defense of Debussy’s writings it was deemed “the most serious counterrevolutionary incident prior to the Cultural Revolution.” He Luting’s interrogation, torture and violent abuse—much of it unfolding on live television—has been described as the “bravest stand by any musicians against totalitarianism.” He Luting’s suffering was not an isolated case. The conductor and timpanist of the Shanghai Symphony, Lu Hongen, was an outspoken critic of the Cultural Revolution and famously tore up Mao’s Little Red Book. Like countless other musicians he faced dire punishment for his sympathy with Western culture. After he was arrested, Lu took to humming Beethoven’s Missa solemnis in his cell. When they decided to execute him, he said to his cellmate, “If you ever get out of here alive, would you please do two things: One is find my son, and the other is go to Vienna, go to Beethoven’s grave … and tell him that his Chinese disciple was humming the Missa solemnis as he went to his execution.”

In Maoist China, musicians were persecuted and executed for defending a musical culture that was not their own. But let us not forget that much of Chinese traditional music was also banned. All musical creations had to be modeled after eight works approved by Jiang Qing, and had to serve as revolutionary propaganda. Modeled on soviet-style cultural bureaucracy, a doctrine of socialist realism required loyalist and heroic works celebration a new socialist Chinese culture, with “varying degrees of tolerance for indigenous traditions and Western influence.” Mao believed in the power of the arts to support, and in the wrong hands to undermine the cause of socialism. He intervened periodically in cultural matters and many of the political campaigns that disrupted the period had cultural components. He initiated vindictive policies on writers and artists, and countless musicians, teachers and educators were sent to do physical labor in the hinterland. The Cultural Revolution, which actually turned out to be a veritable Cultural Nightmare, ended with Mao’s death in September 1976, and the arrest of his widow and their closest associates shortly thereafter. Not long after the establishment of Sino-American relations, Isaac Stern made his historic visit to China in 1979 and reinstated Beethoven as a powerful symbol of classical music in China. Learn more about that period in our next episode entitled Beethoven in China: The Reawakening.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Missa Solemnis “Credo”

You May Also Like

-

Beethoven in China: The Beginnings The Chinese Buddhist monk Li Shutong was a master painter, dramatist, calligrapher, poet, and musician.

Beethoven in China: The Beginnings The Chinese Buddhist monk Li Shutong was a master painter, dramatist, calligrapher, poet, and musician. -

How Debussy changed a Scholar’s fate Fifty years have passed since China’s Cultural Revolution, during which citizens were severely oppressed by restrictions on culture.

How Debussy changed a Scholar’s fate Fifty years have passed since China’s Cultural Revolution, during which citizens were severely oppressed by restrictions on culture.

More Society

-

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia "It's really changed how we view music and what it can do for people"

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia "It's really changed how we view music and what it can do for people" -

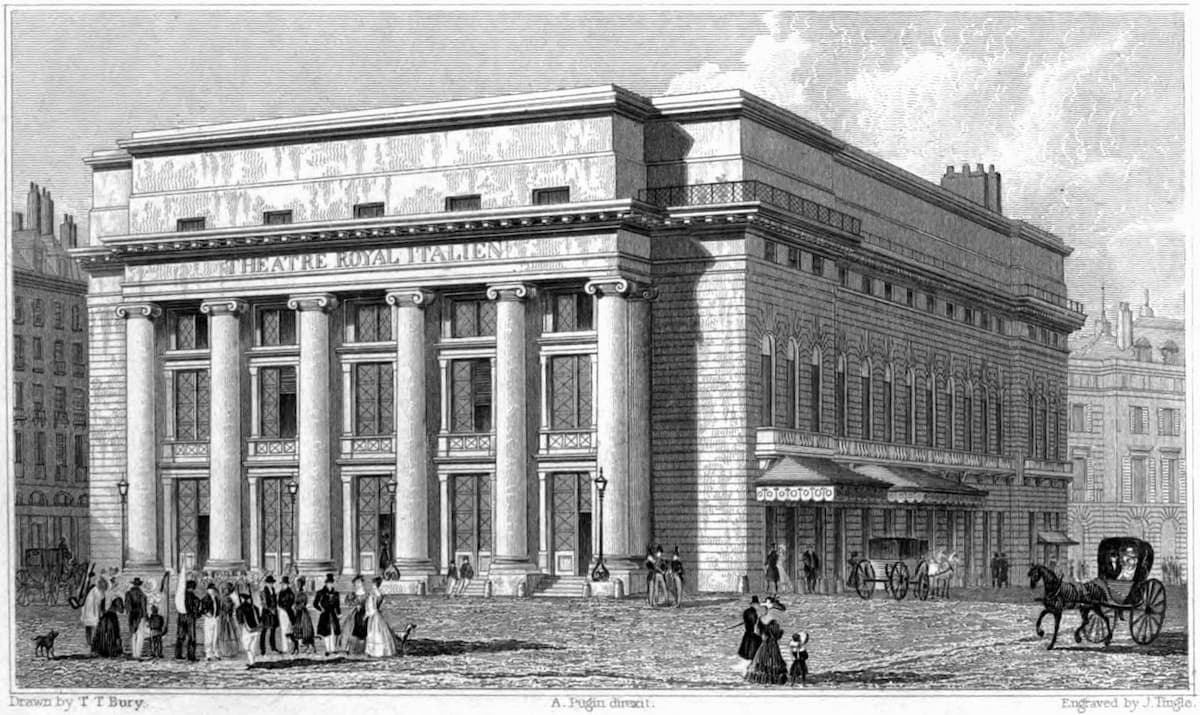

Opéra-Comique at Salle Favart Discover the history and tragic fire of the official Théâtre de l'Opéra-Comique

Opéra-Comique at Salle Favart Discover the history and tragic fire of the official Théâtre de l'Opéra-Comique -

Cello Lament for The Sycamore Gap Tree Italian cellist and composer Riccardo Pes’ “Lament for the Tree”

Cello Lament for The Sycamore Gap Tree Italian cellist and composer Riccardo Pes’ “Lament for the Tree” -

The Gürzenich in Cologne Learn about some famous premieres here

The Gürzenich in Cologne Learn about some famous premieres here

Since I was teaching Chinese history at the time of the Cultural Revolution, and was once a native Philadelphian, I followed Ormandy and his Chinese tour of 1973 with some interest (this was a time of brief opening to to classical music in ’73, permitted briefly by Jiang Qing). By ’74 the bars were down again and Beethoven, joined by Respighi, were the victims of a political campaign, presumably masterminded by JQ (one wonders how many participants even knew who Respighi was).