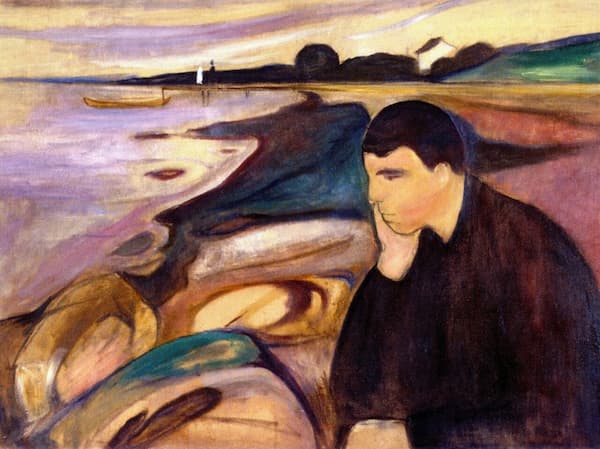

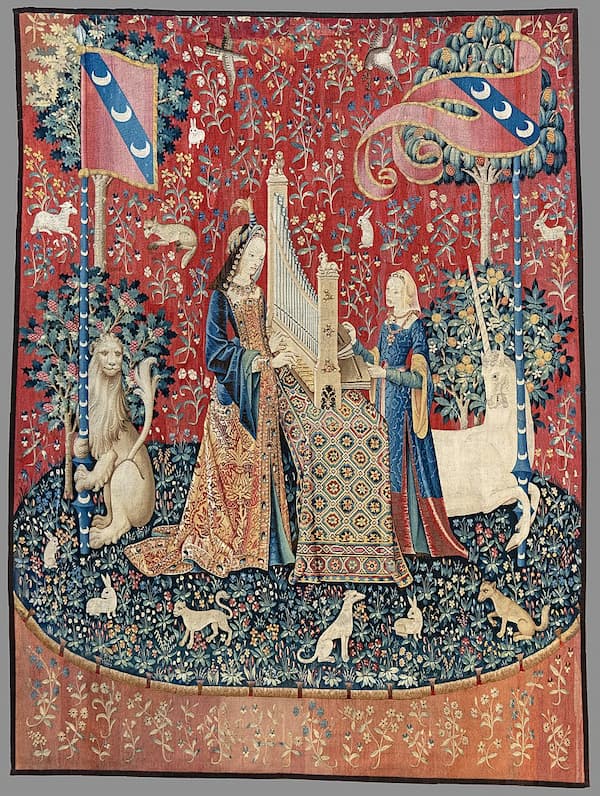

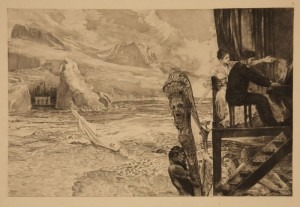

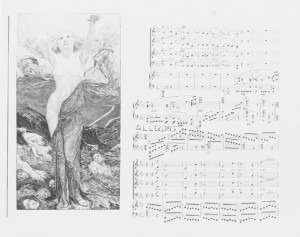

Between the orbits of the planets Mars and Jupiter lays a vast region of space occupied by numerous irregularly shaped celestial bodies. Known as asteroids and minor planets, this so-called asteroid belt was formed by violent primordial collisions. Scientist have long been mapping this area for objects that might become a danger to earth, and on 18 September 1993 a new main-belt asteroid was discovered and christened “22369 Klinger.” In this case, Klinger refers to the Leipzig-based painter, sculptor and printmaker Max Klinger (1857-1920), whose impact shook the artistic community in Fin de siècle Vienna to its foundation. Klinger is primarily known as the sculptor of a Promethean image of Ludwig van Beethoven. His marble statue of the heroic composer was the center of attention in the Vienna Secession exhibit of 1902. Yet, roughly a decade earlier, Klinger had sent another expression of what he termed “visible music” to Vienna. In a unique form of artistic convergence, Kinger’s Brahmsphantasie contains 41 engravings, etching and lithographs on compositions by Johannes Brahms. These graphic images appear in dialogue with musical scores of five songs and the Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny) Op. 54 for chorus and orchestra by Johannes Brahms. The graphic images are not illustrations, but as the title indicates, independent fantasies on the music and the texts.

Between the orbits of the planets Mars and Jupiter lays a vast region of space occupied by numerous irregularly shaped celestial bodies. Known as asteroids and minor planets, this so-called asteroid belt was formed by violent primordial collisions. Scientist have long been mapping this area for objects that might become a danger to earth, and on 18 September 1993 a new main-belt asteroid was discovered and christened “22369 Klinger.” In this case, Klinger refers to the Leipzig-based painter, sculptor and printmaker Max Klinger (1857-1920), whose impact shook the artistic community in Fin de siècle Vienna to its foundation. Klinger is primarily known as the sculptor of a Promethean image of Ludwig van Beethoven. His marble statue of the heroic composer was the center of attention in the Vienna Secession exhibit of 1902. Yet, roughly a decade earlier, Klinger had sent another expression of what he termed “visible music” to Vienna. In a unique form of artistic convergence, Kinger’s Brahmsphantasie contains 41 engravings, etching and lithographs on compositions by Johannes Brahms. These graphic images appear in dialogue with musical scores of five songs and the Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny) Op. 54 for chorus and orchestra by Johannes Brahms. The graphic images are not illustrations, but as the title indicates, independent fantasies on the music and the texts.

The origin of this unique work of art grew from a misunderstanding between Brahms, Klinger and the publisher Fritz Simrock. Simrock commissioned Klinger to create title pages for two of Brahms’s Lieder collections, his Op. 96 and 97. Brahms, however, found the imagery alarming, without relation to his music and rejected their inclusion. Simrock insisted and used Klinger’s title pages anyway. Over the next nine years, Klinger diligently expanded on the idea and he delivered a leather-bound presentation of the Brahmsphantasie to the composer on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. Uniquely, Klinger’s work was to be seen and heard, a multimedia composition that extended the impressions made by two-dimensional images into acoustical space. Apparently, Brahms found the relationship between text, images and music entirely intoxicating. His biographer Max Kalbeck reports, “It was double enjoyable for me to have the pleasure of sitting next to Brahms and looking at the Brahmsphantasie with him. Brahms took his place at the piano and we immersed ourselves so deeply in its pages that we both completely forgot about lunch. He lingered for so long on each page and accompanied the images with such affecting remarks that the hours flew by me like minutes.”

The origin of this unique work of art grew from a misunderstanding between Brahms, Klinger and the publisher Fritz Simrock. Simrock commissioned Klinger to create title pages for two of Brahms’s Lieder collections, his Op. 96 and 97. Brahms, however, found the imagery alarming, without relation to his music and rejected their inclusion. Simrock insisted and used Klinger’s title pages anyway. Over the next nine years, Klinger diligently expanded on the idea and he delivered a leather-bound presentation of the Brahmsphantasie to the composer on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. Uniquely, Klinger’s work was to be seen and heard, a multimedia composition that extended the impressions made by two-dimensional images into acoustical space. Apparently, Brahms found the relationship between text, images and music entirely intoxicating. His biographer Max Kalbeck reports, “It was double enjoyable for me to have the pleasure of sitting next to Brahms and looking at the Brahmsphantasie with him. Brahms took his place at the piano and we immersed ourselves so deeply in its pages that we both completely forgot about lunch. He lingered for so long on each page and accompanied the images with such affecting remarks that the hours flew by me like minutes.”

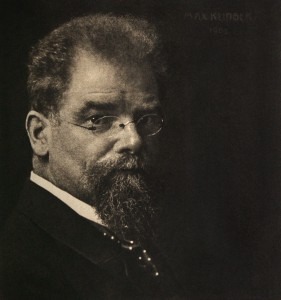

Max Klinger

Credit: http://photoseed.com/

Johannes Brahms: Schicksalslied (Song of Fate) Op. 54