Not all carols celebrate the birth of Jesus; some commemorate the other actions that resulted from the news of that birth.

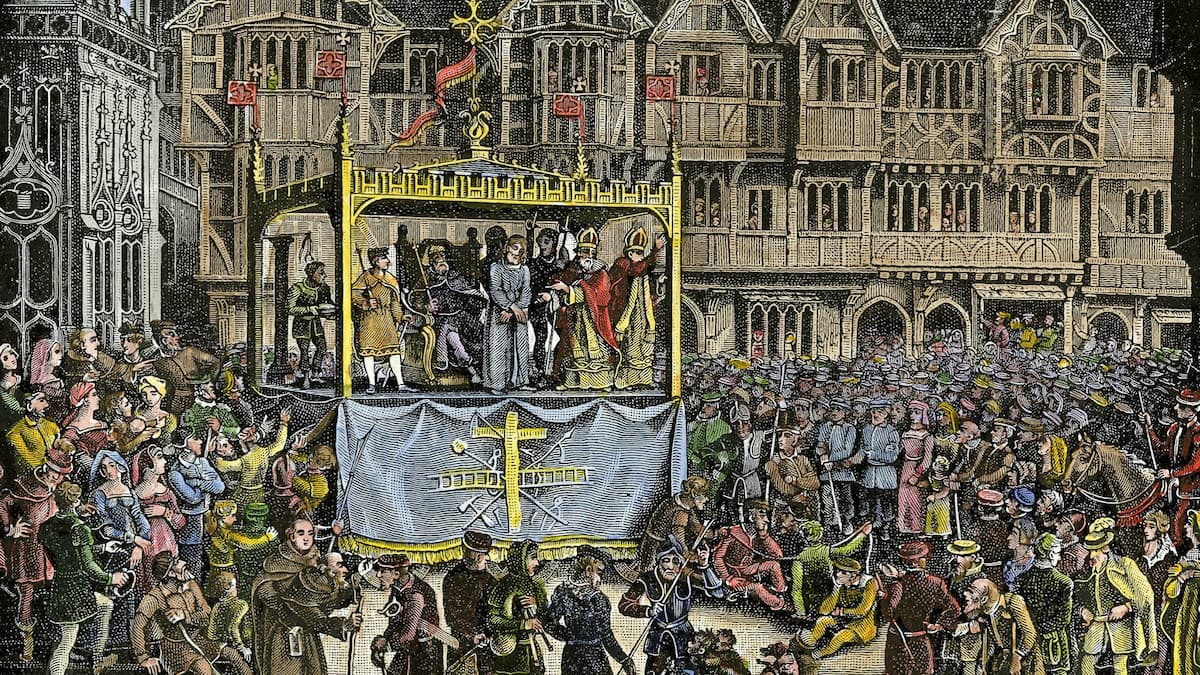

Starting in the 14th century, the English city of Coventry held annual mystery plays where stories from the Bible would be acted (and sung) as tableaux, performed by the craft guilds of the city. Coventry wasn’t the only city to have these, but the carol we’re looking at today is from one of the Coventry guilds and carries the title of The Coventry Carol.

It was performed as part of The Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors mystery play. This play would have been put on in June. The plays, including this one, were first recorded in 1392–93 and ran for nearly 200 years until they were suppressed in 1579 when the Protestant Queen Elizabeth thought the plays were too Catholic. The Carol lived on, however.

Illustration of a mystery play performance from Thomas Sharp’s Coventry Mysteries, 1825, hand coloured

This is a carol for women, because the story it sets is one of the grimmest of the Christmas season: the Massacre of the Innocents by King Herod, who, having heard of the birth of Jesus, ordered all male children in Bethlehem below the age of 2 to be killed.

Lully, lullah, thou little tiny child,

Bye bye, lully, lullay.

Thou little tiny child,

Bye bye, lully, lullay.

O sisters too, how may we do

For to preserve this day

This poor youngling for whom we sing,

“Bye bye, lully, lullay”?

Herod the king, in his raging,

Chargèd he hath this day

His men of might in his own sight

All young children to slay.

That woe is me, poor child, for thee

And ever mourn and may

For thy parting neither say nor sing,

“Bye bye, lully, lullay.”

Peter Paul Rubens: The Virgin and Child surrounded by the Holy Innocents, 1616 (photo by Jean-Pol Grandmont) (Paris: Louvre Museum)

This is a song sung by the mothers, looking to what will be happening in the evening and attempting to sing a lullaby to their child. The story comes from the second book of Matthew, and the children, considered the first martyrs of the church, were called The Holy Innocents. Fortunately, most current Biblical scholars think the story is false and didn’t happen.

Traditional: Coventry Carol (arr. R. Allain for choir) (Ikon; David Hill, cond.)

In this setting by Richard Allain, the song begins quietly and builds towards the third verse when Herod’s actions are revealed. At the end, however, the mothers’ song quiets and returns to being a lullaby. Although this arrangement plays with the harmonies, adding dissonances to heighten the terror of the story, it ends with a major-key ending, known as a Picardy third cadence. Common in medieval music, to our modern ears, the Picardy third ending brings a note of optimism.

The author of the poem is unknown, but the text was written down by Robert Croo, an organizer of the mystery plays, in 1534 in his prompt book. The prompt book was transcribed by antiquarian Thomas Sharp in 1817 and, after Croo’s original manuscript was lost in 1879 in a fire at the Birmingham Free Library, was the only source of original information on the plays.

The oldest setting of the melody comes from 1591, written out by (although perhaps not composed by) Thomas Mawdyke. As mentioned above, the mystery play would have been traditionally performed in the summer, but during WWII, after the bombing of Coventry and the use of the carol in a BBC broadcast in 1940, it came back into use. The BBC program closed with a singing of the carol in the bombed-out church of the city.

BBC Christmas Day Broadcast, 1940, with Provost Howard, following the 15 November bombing of Coventry

Mawdyke’s music was part of an effort in 1591 to revive the mystery plays. It was unsuccessful, but the plays were revived in Coventry starting in 1951.

Traditional: Coventry Carol (Emily Van Evera, soprano; Charles Daniels, tenor; Simon Grant, bass-baritone; Taverner Choir; Taverner Consort; Andrew Parrott, cond.)

In this simpler version, the Picardy third ending is very clear.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter