Ottorino Respighi

Through his life, Respighi studied the Italian composers of the 16th and 17th century, resulting in works such as Ancient Airs and Dances, based on pieces for lute and viola by various Renaissance composers, and The Birds, which was based on Baroque bird pieces. Similarly, Toccata is modelled on the keyboard toccatas of Frescobaldi, and the concerto style developed by Vivaldi and Corelli, and, in particular, an oboe concerto by Alessandro Marcello.

Marcello: Oboe Concerto in D minor: II. Adagio

(József Kiss, oboe; Budapest Ferenc Erkel Chamber Orchestra )

The work opens with not the usual contest between orchestra and soloist but is more like a long slow introduction that keeps threatening to become the expected Allegro but, each time, is turned away. The opening is more like a dialogue between piano and orchestra, making it closer to the 17th century idea of a fantasia, although Respighi does not use that term. A delicate duet between the cello and the oboe slows the movement down (03:15).

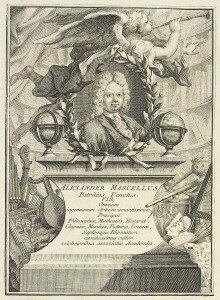

Alessandro Marcello

Now, after what have been, in effect, two slow movements, the forward motion has nearly stopped. It restarts, however, with a cadenza that wakes up both the audience and the pianist (17:30). Here is where both the orchestra and soloist come into their own as virtuoso players. This last ‘movement’ / section is similar to the Allegro Rondos that feature in so many 17th century concertos – the soloist and orchestra a free time to spin out fast motifs but return again to a main theme.

Respighi: Toccata, P. 156 (Geoffrey Tozer, piano; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra ; Edward Downes, cond.)

The title of Toccata comes into its own in the final section, where the final theme is developed through, as Respighi puts it ‘manifold rhythmic transformations.’

Respighi’s work makes us re-think not only the piano concerto, but the virtuosity demanded of both the soloist and the orchestra.