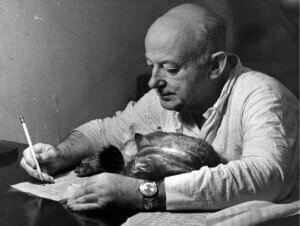

Henry Cowell composing with helping cat

Here’s the fuguing tune “Northfield” sung in the rather nasal style of the Sacred Harp (a publication that contained dozens of these fuguing tunes) tradition: you’ll hear everyone sing the first line together, then each with their own entry, and then together for the last line of the verse.

Ingalls: Northfield (Word of Mouth Chorus; Larry Gordon, cond.)

Henry Cowell, when he started writing his Hymns and Fuguing Tunes, did not use hymns from early American sources. Instead, he wrote his own hymns. He took inspiration from the early American hymnals and then asked himself “What would have happened in America if this…style had developed?” He uses the old modes (neither major nor minor) and the open chords of the original and carries them forward to the 20th century.

His first Hymn and Fuguing Piece, as it was then called, was written for piano in 1943. He lost his first hymn but, since he was the composer, wrote a new one to go with the fuguing piece. This was turned into Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 1 and was given its premiere in New York City in 1944.

Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 2 also made its debut in 1944. The critic Virgil Thomson, in his review of a performance in 1949, concluded that he “was sorry when it ended, because it had made music all the way through.” Here Cowell’s hymn sounds not unlike Bach’s “A Mighty Fortress is Our God,” but it differs, particularly in the moving inner lines.

Cowell: Hymn and Fuguing Tune No.2: Hymn (Northwest Chamber Orchestra Seattle; Alun Francis, cond.)

The fuguing tune takes up the idea of the contrapuntal entrances and spins them out.

Cowell: Hymn and Fuguing Tune No.2: Fugue

As we start to catch on to Cowell’s style in Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 3, we can start to hear the strengths in the hymn sections. These are clearly based on an older style, but he takes them on with more freedom, using more interesting rhythms, and exploiting the tonal colour of the orchestra that’s available to him. He rewrote this work later for piano.

Cowell: Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 3 (Louisville Orchestra; Jorge Mester, cond.)

Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 4 was written for 3 instruments, either 3 voices (Soprano, Alto, Bass) or it could be performed by other woodwinds or even strings.

Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 5 started out as a vocalise for 5 voices. Later that year (1946) he arranged it for string orchestra and in 1953, for full orchestra. This eventually became the first two movements of his symphony No. 10.

Cowell: Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 5 (Northwest Chamber Orchestra Seattle; Alun Francis, cond.)

His Hymns and Fuguing Tunes were written for a wide range of instrumental combinations, but none more striking than the last, No. 18 (1964), written for two instruments on the opposite ends of the musical range: soprano saxophone matched with a contra-bass saxophone.

Cowell: Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 18 (Paul Cohen, soprano saxophone; Ulrich Krieger, contrabass saxophone)

You can hear how much Cowell has had fun composing in an old, strict style but with a modern set of ingredients.