Medical research has clearly shown that infants are active listeners! Their attention is selectively drawn to particular musical genres, and to particular performing styles associated with maternal singing. Regardless of culture and living environment, infants reveal a clear preference for the universal musical form of the lullaby. Regional, stylistic or historical variants aside, the lullaby is a vocal piece designed to lull a child to sleep with repeated formulae, or used to soothe a sick infant. The text can instill a number of cultural and societal values, and as a vocal or instrumental piece it appears in Western art music of all periods. With his Op. 49, No. 4, a lullaby composed to warble the son of a former flame to sleep, Johannes Brahms composed probably the most famous example of the genre. The “Wiegenlied” became hugely popular around the world, with countless and varie d arrangements appearing overnight. However, his most touching creation is the gentle lyrical Geistliches Wiegenlied (Sacred Lullaby), Op. 91, No. 2. Scored for contralto, piano and viola, the composition builds around the old Christmas folk song Josef, lieber Josef mein. Although published in 1884, the Geistliches Wiegenlied originated 20 years earlier as a gift for Joseph Joachim and Amalie Schneeweiss, his wife to be.

Medical research has clearly shown that infants are active listeners! Their attention is selectively drawn to particular musical genres, and to particular performing styles associated with maternal singing. Regardless of culture and living environment, infants reveal a clear preference for the universal musical form of the lullaby. Regional, stylistic or historical variants aside, the lullaby is a vocal piece designed to lull a child to sleep with repeated formulae, or used to soothe a sick infant. The text can instill a number of cultural and societal values, and as a vocal or instrumental piece it appears in Western art music of all periods. With his Op. 49, No. 4, a lullaby composed to warble the son of a former flame to sleep, Johannes Brahms composed probably the most famous example of the genre. The “Wiegenlied” became hugely popular around the world, with countless and varie d arrangements appearing overnight. However, his most touching creation is the gentle lyrical Geistliches Wiegenlied (Sacred Lullaby), Op. 91, No. 2. Scored for contralto, piano and viola, the composition builds around the old Christmas folk song Josef, lieber Josef mein. Although published in 1884, the Geistliches Wiegenlied originated 20 years earlier as a gift for Joseph Joachim and Amalie Schneeweiss, his wife to be.

Johannes Brahms: Geistliches Wiegenlied, Op. 91 No 2

Undoubtedly you know Franz Schubert’s 1816 setting of an anonymous poem with the words “Schlafe, schlafe, holder, süsser Knabe” (Sleep, sleep, dear sweet boy). However, Schubert composed at least two other equally tender lullaby settings. The Wiegenlied D. 867 is based on a poem by the highly talented, versatile and ambitious bard Johann Gabriel von Seidl. A contemporary of the composer, Seidl’s poem unfolds with considerable flair and immediately invoke a hypnotic atmosphere:

Undoubtedly you know Franz Schubert’s 1816 setting of an anonymous poem with the words “Schlafe, schlafe, holder, süsser Knabe” (Sleep, sleep, dear sweet boy). However, Schubert composed at least two other equally tender lullaby settings. The Wiegenlied D. 867 is based on a poem by the highly talented, versatile and ambitious bard Johann Gabriel von Seidl. A contemporary of the composer, Seidl’s poem unfolds with considerable flair and immediately invoke a hypnotic atmosphere:

How carelessly the eyes’ childlike heaven

Closes, laden with slumber!

Closes them thus, when one day the earth calls you;

Heaven is within you; outside is joy!

_____________________________

As an angel fold your little hands,

Fold them thus one day when you go to rest!

Dreams are beautiful when you pray, and your

Awakening rewards you no less than your dream.

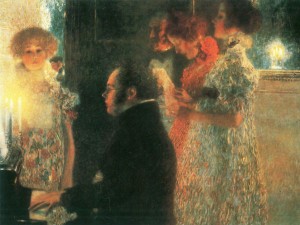

Schubert takes this spellbinding atmosphere and musically encodes it into a Lied of glowing innocence. Delicate figuration, simplicity of expression and a narrow melodic range mirrors the simplicity a child could easily understand. Above all, we are “drawn into another world and we stay there, under Schubert’s spell, until the child falls asleep and allows us to leave the room.”

Franz Schubert: Wiegenlied, D. 867

Schubert

Robert Schumann: Wiegenlied, Op. 78 No 4

Clara and Robert Schumann

What will you do now, poor lamb?

You have a child but no man!

Ah, why worry poor mite,

I’ll sing through the livelong night;

Hush-a-bye baby, my darling boy,

Nobody cares about us!

Alban Berg: Wozzeck, “Wiegenlied” Act 1, Scene 3