Imagine you’re a poor single woman in eighteenth century Venice. You have no family, no fortune, and your career options are – obviously – limited. Every year during Carnival, hundreds of wealthy men descend on Venice, busy taking their Grand Tours of the Continent, and you’re able to make some much-needed money off their desires.

Once you get pregnant, though, you have few options. You could drop your infant into one of the dark Venetian canals, as many women were known to do. Or you could leave your infant at an institution known as the Ospedale della Pietà, where unwanted children were accepted through a tiny baby-sized opening called a scaffeta. No questions will be asked, and you won’t be prosecuted for any crimes.

Best of all, the unwanted babies left at the Ospedale were taken care of. The boys learned a trade and left at the age of sixteen, while many of the girls supported the institution by sewing, embroidering, and doing other important domestic work (these girls were known as the “figlie di comun”). Ultimately, those young women would get married or take the veil and leave the Ospedale.

Not all the girls, however. Because when they were around nine years old, they underwent a musical examination. The most musically talented tenth – known as the “figlie di choro” – were given an incredible opportunity: to receive a rigorous musical education alongside their female peers. (Those peers could also include scholarship students and paying students who wanted a first-rate musical education.)

That being said, life as a performer in the ospedale certainly wasn’t for everyone! Members of the figlie di choro were expected to remain cloistered and virginal, live in the Pietà for the rest of their lives, attend daily religious services, teach the younger girls, and devote their lives to music and supporting the ospedale. Some decided against such a life and ultimately married, while others became nuns. The remaining women, however, had the honor of performing in the Pietà’s internationally renowned all-female instrumental and choral ensembles.

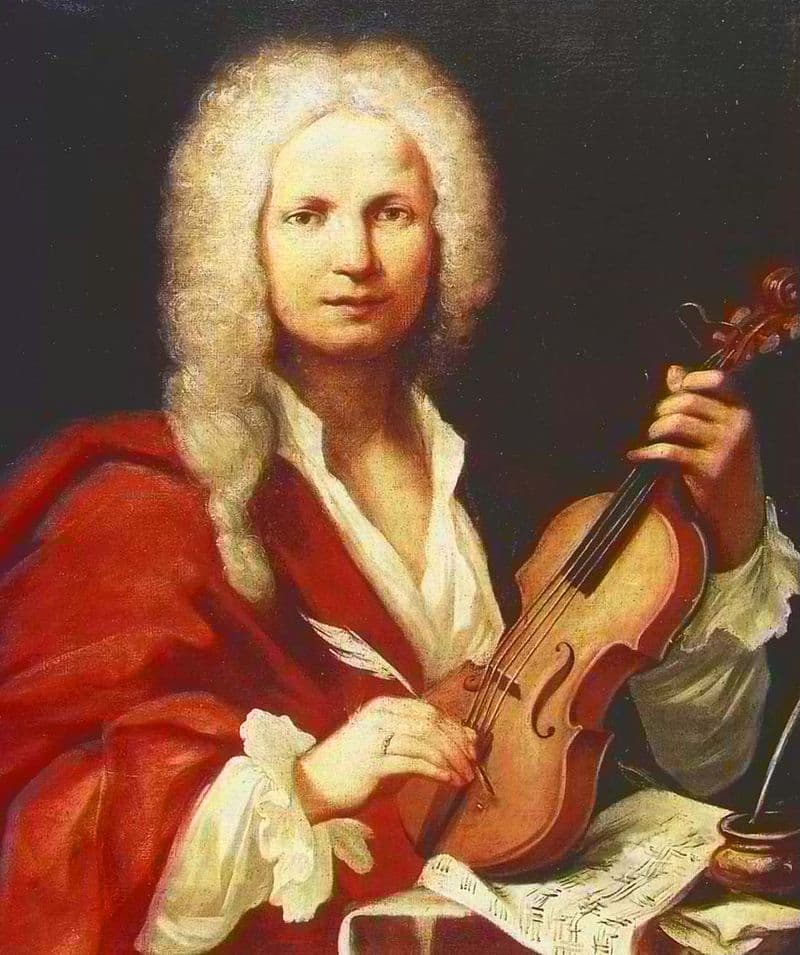

Antonio Vivaldi, 1723

Their repertoire was extensive. They played for religious services such as compline, vespers, and mass, and even performed oratorios, as well as special shows for visiting dignitaries. Interestingly, they performed behind ornate grates, ostensibly to preserve their modesty. (But this arrangement also had the effect of obscuring any physical defects they may have inherited. Not surprisingly, since many of the girls’ mothers were impoverished and/or prostitutes, congenital health issues were relatively common.)

Vivaldi Gloria at La Pieta

These ensembles performed at a high level, and for reasons that were unique to the ospedale. Importantly, the membership was stable, which enabled the women to build ensemble skills with their colleagues, and they were also allowed a great deal of rehearsal time. Consequently, their virtuosic performances became a major European tourist destination. (They were especially popular during Lent, when the opera houses were closed.) The better the orchestra played and chorus sang, the more tourists who visited. The ultimate goal was to add to the organization’s coffers so that they could continue to save and educate the unwanted.

Much of the teaching that occurred within the walls of the ospedale was by women; however, outsiders were hired as teachers, too. Violinist, priest, and composer Antonio Vivaldi worked at the ospedale from 1703 until 1715, and again from 1723 to 1740. His duties included teaching young women music, conducting their instrumental ensembles and choirs, buying instruments, and even writing music for them to perform. Although we don’t know all of their names, some of his students went on to achieve international renown, such as Anna Maria dal Violin. (Sometimes when the women’s identities were unknown, they were granted surnames based on the instruments they played or vocal parts they sang.) Vivaldi wrote multiple violin concertos for Anna Maria, and some savvy listeners even claimed she was one of the greatest violinists of her generation, male or female.

The legacy of the ospedale lives on. Even today, musicians still perform the works that Vivaldi wrote for these remarkable women so many generations ago! Despite Vivaldi’s surge in popularity during the late twentieth century, the inspirational role his virtuosic female colleagues played isn’t often discussed. Hopefully in time the ladies of the Pietà will eventually become as famous as their teacher.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter