Benet Casablancas: Four Darks in Red, After Rothko

Although normally on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, Mark Rothko’s 1958 Four Darks in Red was on loan to the Tate Modern in London when Catalan composer Benet Casablancas (b. 195b) saw the painting.

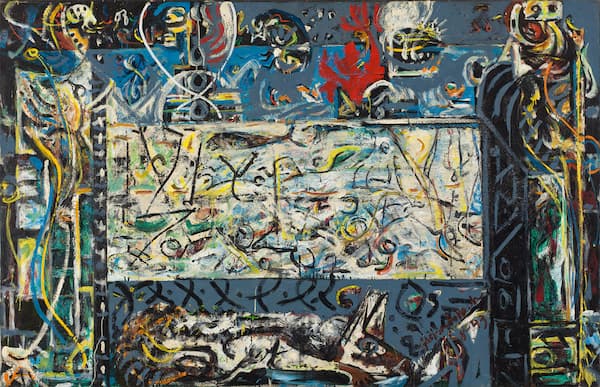

Rothko: Four Darks in Red, 1958 (Whitney Museum of American Art)

The work is in keeping with other Rothko works from the late 1950s, where red, maroon, and saturated black paints were all central to his palette. Set in a luminous red background, 4 different-sized triangles emerge and recede. The canvas is enormous – nearly 10 feet wide (101 13/16 × 116 3/8in. (258.6 × 295.6 cm)) – and intended to be viewed close up, not at a distance. The result is that the viewer becomes engulfed in Rothko’s red world. The canvas is darker (and heavier) at the top and falls to lighter and smaller rectangles at the bottom. ‘Rothko believed that such abstract perceptual forces had the ability to summon what he called “the basic emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, and doom”.’

Casablancas wrote his chamber symphony, Four Darks in Red, After Rothko, in 2008, after seeing the painting in London, on commission by the Miller Theatre at Columbia University in New York. Other works by Casablancas also use paintings as their point of inspirations, which is all part of his search for creative feedback between different fields in the arts.

Benet Casablancas

Focusing on the darkest rectangle, the one second down from the top, Casablancas says about his work: “The formal organization of the musical piece—the score consists of four sections that develop seamlessly—somehow reveals a connection with the four major areas that shape the picture, read from top to bottom (so, for example, the dark zone motivates the general shift toward the lower registers of the orchestra). The slow section that opens Part IV gradually moves toward a contemplative and more ecstatic atmosphere, whose quietness leads to a suspension of time and the threshold of silence. At this point, the score includes the following quotation from Rothko: “Silence is so accurate”.’

He concludes by saying that, ‘In any case, as is typical of my musical thinking, the mood of the piece is never descriptive or programmatic. It is an empathic, abstract response to the deep admiration I feel for the language and achievement of this great artist, for his work’s powerful presence and naked expressivity, animated by intense internal drives’.

Benet Casablancas: Four Darks in Red, After Rothko (London Sinfonietta; Felix Krieger, cond.)

The opening is active and immediately pushes the listener forward until the downward movement into the lower notes, signalled by a low note on the piano and the gradual addition of the horns. As the speed slows, we end up in a solo on the alto flute (04:00), which leads into the third section.

The third section is written like a scherzo, with a contrasting middle section, and with a significant conclusion. The final section, using stretta, piles up the voices, throwing references (highly stylized) to American popular music into the mix, before coming to brilliant conclusion.

By using Rothko’s upside-down layering, with the heaviest section at the top, above a lighter and smaller bottom section, Casablancas turns a normal symphonic work inside out. If we think of Rothko’s work as a vertical structure, Casablancas’ work is a horizontal one, stretching forward and backward in time. By concluding with a lighter, one might almost say humorous ending, he gives us Rothko’s light small rectangle in sound.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter