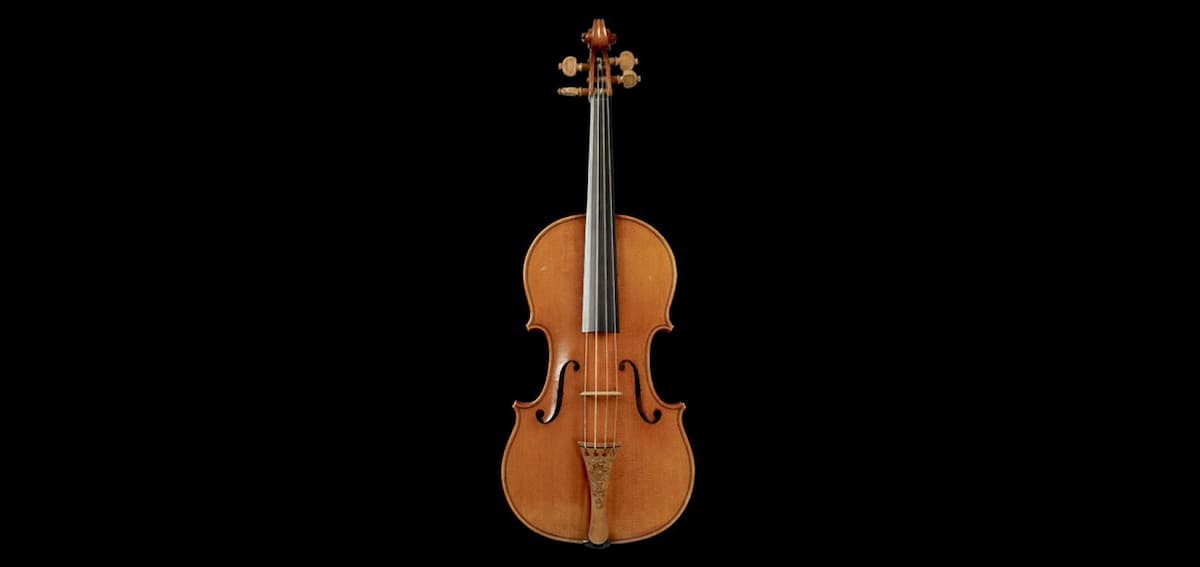

The history of classical music is brimming with storied musical instruments. Chief among them is the Messiah Stradivarius, believed to be the most expensive violin in the world, celebrated for its pristine condition and astronomical value.

The Messiah Stradivarius

Today we’re delving into the story behind this iconic violin, exploring its origins, illustrious owners, and the legacy it has left behind…and why it never leaves its glass case.

Origins as a Stradivari Family Heirloom

The story of the Messiah Stradivarius began in the quaint town of Cremona, Italy, where it was crafted by the legendary luthier Antonio Stradivari.

Born in 1644, Stradivari honed his skills under the guidance of his teacher, Nicolo Amati, but ultimately developed his own distinctive style. Eventually, Stradivari became known as the greatest violin maker in history.

Antonio Stradivari

This particular violin was crafted in 1716, during Stradivari’s so-called “Golden Period,” when he produced his most sought-after instruments.

It appears that this particular violin was never sold during Stradivari’s lifetime. Historians aren’t sure why.

After Stradivari died at a ripe old age in 1737, his sons kept this violin for themselves. The website Tarisio.com claims that Antonio’s sons, Francesco and Paolo Stradivari, retained ownership until 1775.

Two Great Collectors and a New Nickname

Count Cozio di Salabue, c. 1820

That year, Paolo – who was born when Stradivari was in his mid-sixties – died. Around the time of Paolo’s death, the violin was sold to Count Cozio di Salabue and therefore gained the temporary nickname of the “Salabue” Stradivari.

Cozio was one of the first obsessive violin collectors in music history. We owe a great deal of knowledge about eighteenth-century violin-making to his rigorous note-taking.

The Count kept the “Salabue” until 1827 when it was sold again, this time to a man named Luigi Tarisio. (Yes, he’s who Tarisio.com is named after!) Tarisio came from humble beginnings as a farmer, but eventually, through wit and luck, became a dealer of renown.

Tarisio often traveled to Paris to meet with violinists and other dealers. While there, he’d boast to his friends about the immaculate 1716 Stradivari he’d left at home in Italy.

Eventually, his friends got tired of hearing about it. Legend has it that an exasperated violinist named Jean-Delphin Alard eventually snapped back, “Ah, ça, votre violon est donc comme le Messie; on l’attend toujours, et il ne parait jamais” (“Then your violin is like the Messiah: one always expects him but he never appears”).

This nickname stuck, and the violin has been known as the Messiah ever since!

Delphin Alard: Duos brillant, Op. 27, No. 3 (Alexandr Bulov, violin; Ilya Gringolts, violin)

Jean-Baptise Vuillaume and Family

Jean-Baptise Vuillaume

Tarisio was never able to bring himself to sell the Messiah, so it was only sold after his death in 1854.

Who was the buyer? A cunning luthier and businessman by the name of Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, who could copy instruments so convincingly that his fakes could go undetected.

Vuillaume modernized the Messiah somewhat, changing its pegs, replacing its original tailpiece with one featuring a nativity scene, lengthening the neck to modern proportions, and switching out the bass bar inside. These were relatively minor adjustments that helped make it possible to play contemporary repertoire on the instrument.

Vuillaume was extremely protective of the Messiah, keeping it in a glass case and only very rarely allowing it to be seen by the public.

Its international debut, so to speak, only came in 1872, when it was shipped to England and exhibited at the Exhibition of Instruments in the South Kensington Museum.

After Vuillaume died in 1875, the Messiah passed to his daughter Jeanne-Emilie, as well as her husband…who was none other than Jean-Delphin Alard, who had originally given the violin its nickname, years before!

Jeanne-Emilie was thirteen years younger than Alard, and he died before she did, in 1888.

W.E. Hill and Sons and the Ashmolean Museum

In 1890, the famous British dealership W.E. Hill and Sons was hired to sell the instrument, and it was sold for 2600 pounds. At the time, it was the highest price ever paid for a violin.

The violin passed through the hands of a few different owners – even returning to W.E. Hill and Sons for a period of nine years – until the dealers bought it back permanently in 1931.

In 1939, W.E. Hill and Sons donated a collection of priceless instruments to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England. The pride and joy of that collection was the Messiah.

Today, you can go visit the Messiah Stradivari at the Ashmolean Museum. But, much as it was in Vuillaume’s day, the instrument is kept behind glass walls, barely ever touched or played.

Instead, its main function is to be a relic. It’s a blueprint for luthiers and historians curious about the history of Stradivari and Italian violin-making, and a reminder to viewers that great violins aren’t just tools for making music; they’re works of art in their own right.

Because of how little the Messiah has been played compared to other instruments of its vintage if it was ever sold, it would probably become the most expensive violin in the world. Its value has been estimated at around $20 million, but it’s more accurate to say it’s priceless.

Today, the Messiah Stradivarius is an inspiring – if slightly eerie! – relic of the golden age of violin-making. It serves as a tribute to the enduring legacy of Stradivari’s craftsmanship. Next time you’re in Oxford, be sure to stop by its glass case and say hello.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter