Niccolò Machiavelli

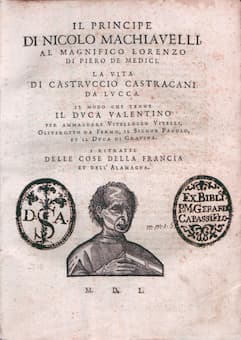

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) is frequently called the father of modern political philosophy and political science. Machiavelli’s best-known book Il Principe (The Prince) was written around 1513 and contemplates a new type of ruler not guided by the conventions of heredity. For Machiavelli, the social benefits of stability and security can be achieved in the face of moral corruption. “A ruler must be concerned not only with reputation,” he writes, “but also must be willing to act unscrupulous at the right times.” He expresses his believes that for a ruler, “it is better to be widely feared than to be greatly loves, “and that there is “necessity for the methodical exercise of brute force of deceit, including extermination of entire noble families, to head off any chance of a challenge to the prince’s authority.”

Niccolò Machiavelli: Il Principe

The Catholic Church quickly banned the book, humanists viewed it decidedly negatively, and the adjective “Machiavellian” is still part of our modern vocabulary. As a 20th century scholar writes, “Machiavelli is the only political thinker whose name has come into common use for designating a kind of politics, which exists and will continue to exist independently of his influence, a politics guided exclusively by considerations of expediency, which uses all means, fair or foul, iron or poison, for achieving its ends.”

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio I: Dalle più alte sfere (Rossana Bertini, soprano; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio I: Coppia gentil (Compagnia Dramatodia; Coro Ricercare Ensemble; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)

Machiavelli was born in Florence during tumultuous time with popes waging wars against Italian city-states, and France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire battling for regional influence and control. He descended from an impoverished aristocratic family, and undoubtedly had some basic grounding in music. Besides learning grammar, rhetoric, and Latin, a true gentleman “could not claim to be well educated unless he was also a musician and unless as well as understanding and being able to read music he could also play several instruments.” It is not known if Machiavelli played any instruments, but he certainly must have had a rudimentary grasp of music. It has been rightfully suggested that “Machiavelli carried his youthful fondness for music well into adulthood.” When he was elected Second Chancellor of the Florentine Republic in 1498, Machiavelli distracted himself from work by turning to music. Using his poetic talents, he started to compose songs to be shared with friends over a drink or after a lazy dinner.

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio III: Qui di carne si sfama (Rossana Bertini, soprano; Elena Bertuzzi, soprano; Candida Guida, alto; Paolo Fanciullacci, tenor; Marco Scavazza, baritone; Mauro Borgioni, bass; Compagnia Dramatodia; Coro Ricercare Ensemble; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio III: O mille volte (Compagnia Dramatodia; Coro Ricercare Ensemble; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)

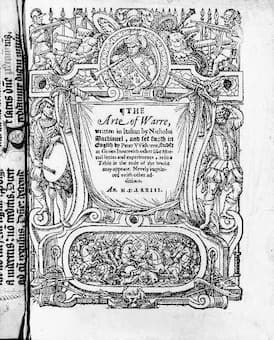

Niccolò Machiavelli: The Art of War

More than anything, however, “Machiavelli enjoyed writing canti carnivaleschi. Sung during the city’s annual carnival celebrations, they were rather earthy texts addressing overtly sexual themes or make fun at religious sensibilities. “Above all, they were all tremendously funny and full of double entendres.” We are not sure how many Machiavelli actually wrote, but six have survived. And there seems to be no indication that he actually set them to music. Machiavelli also reflected on the use of music to communicate in the midst of battle. In his 1519 Art of War, he took a page from Roman and Greek antiquity and expounded on their use of different varieties of music to direct the troops. Machiavelli went as far as to specifying which instruments should be used, by whom, and how. As he writes, “Near the General, I place the trumpets, as better fitted than any other instrument to be heard in the midst of noise of every kind … And near the constables and the battalion commanders, I wish there to be little drums and flutes, played not as they now are in armies, but as they are usually played at banquets.”

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio V: Dunque fra torbid’onde (Paolo Fanciullacci, tenor; Marco Scavazza, baritone; Mauro Borgioni, bass; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio V: Liei solcando il mare (Rossana Bertini, soprano; Elena Bertuzzi, soprano; Candida Guida, alto; Paolo Fanciullacci, tenor; Marco Scavazza, baritone; Mauro Borgioni, bass; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)

Tomb of Machiavelli in Santa Croce, Florence

Machiavelli, however, seems to have been particularly enthusiastic about the role of music in the theatre. His comedy Clizia follows Nicomaco, a lecherous Florentine who recently has taken notice of the beautiful, teenaged Clizia, an orphan girl he and his wife Sofronia have raised since adolescence. Nicomaco’s son Cleandro has also fallen in love with Clizia, but Sofronia outright forbids him to pursue the dowry-less girl. Nicomaco attempts to marry Clizia to his loyal servant Pirro in exchange for perpetual visitation rights. “But Sofronia so masterfully contrives events that, by the play’s end, Nicomaco is returned, with all due opprobrium, to the role of dutiful husband. Cleandro and Clizia are set to be married and the entire household enriched anew by the (unexpected) extravagant dowry promised by Clizia’s long-lost father, who appears seemingly out of nowhere.” That particular play was specifically written for a sumptuous party on 13 January 1525, and well-known actress Barbera Salutati sang light-hearted madrigals before and after each act. It was the first time in history that music had been used to break up a play like this, and it was to change theatre forever. “From that moment on, so-called “intermedio” songs became a regular feature of dramatic performances and, by the end of the 16th century, their popularity had inspired the development of an entirely new form of musical theatre called opera.” And by the way, Barbera Salutati was Machiavelli’s mistress and he personally interspersed the theatrical action with madrigals as to give her a bigger role in the festivities.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio VI: Dal vago e bel sereno (Rossana Bertini, soprano; Elena Bertuzzi, soprano; Candida Guida, alto; Paolo Fanciullacci, tenor; Marco Scavazza, baritone; Mauro Borgioni, bass; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)

Antonio Archilei / Giovanni de’ Bardi / Giulio Caccini / Emilio de’ Cavalieri / Cristofano Malvezzi / Luca Marenzio / Matthias Hermann Werrecore: La pellegrina – Intermedio VI: O che nuovo miracolo (Rossana Bertini, soprano; Elena Bertuzzi, soprano; Candida Guida, alto; Paolo Fanciullacci, tenor; Marco Scavazza, baritone; Mauro Borgioni, bass; Modo Antiquo; Federico Maria Sardelli, cond.)