In festo transfigurationis Domini nostri Jesu Christi, S188/R74

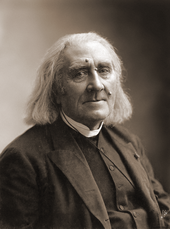

Franz Liszt

It was relatively easy to start this series on Franz Liszt and his romantic conquests. However, it is somewhat more difficult to conclude it. Since Liszt was a fairly discreet lover, there is no hope of having comprehensively covered the entire spectrum of his amorous involvements. As such, my sincere apologies to all ladies and gentlemen, who rightfully should, or might have wished to feature in this series. For the most part — unless you are a pathological basket case like Benjamin Britten who couldn’t keep his hand off little choir boys — it takes two to tango. And Marie Pleyel, one of the most celebrated pianists of the early nineteenth century, clearly understood that concept.

Heinrich Heine ranked Pleyel among the mightiest piano virtuosos of the early nineteenth century, calling “Thalberg a king, Liszt a prophet, Chopin a poet, Herz an advocate, Kalkbrenner a minstrel, Mme Pleyel a sibyl, and Döhler a pianist.” And François-Joseph Fétis, who helped Pleyel to become the head of the piano department at the Brussels Conservatory, wrote: “I have heard all the celebrated pianists from Hullmandel and Clementi up to Liszt but I say that none of them has given me, as has Mme. Pleyel, the feeling of perfection.” Clara Schumann was left speechless after a Pleyel performance, and Hector Berlioz — somewhat predictable — lost his heart. Since Pleyel was socially very well connected, counting Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo among her close personal friends, she was in all respects, on an equal footing with Franz Liszt. Apparently, the battle for supremacy was fought on a mattress in Chopin’s apartment, who vigorously objected to this kind of athletic intrusion. In the end, Marie Pleyel outperformed Franz Liszt in this department as well, as he could only describe her as “insatiable.” As a matter of fact, when it came to women, Liszt needed to be needed! And that applied with equal validity to the bedroom and the piano bench, most preferably in combination.

Marie Pleyel

In 1869, the young American pianist Amy Fay crossed the Atlantic to study piano with Tausig, Kullak and eventually Franz Liszt. She filed meticulous reports to her sister Melusina, which were eventually published under the title Music-Study in Germany. On one hand, Amy was completely infatuated by Franz and his musical magnetism. “In Liszt I can at last say that my ideal in something has been realized. He goes far beyond all that I expected. Anything so perfectly beautiful as he looks when he sits at the piano I never saw, and yet he is almost an old man now. I enjoy him as I would an exquisite work of art. His personal magnetism is immense, and I can scarcely bear it when he plays. He can make me cry all he chooses, and that is saying a good deal, because I’ve heard so much music, and never have been affected by it.” Yet, she would have absolutely nothing to do with him sexually. “But you need not fear that I am ‘giving up American standards’ because I reverence Liszt so boundlessly. Everything is topsy-turvy in Europe according to our moral ideas, and they don’t have what we call ‘men’ over here. But they do have artists that we cannot approach!”

Amy Fay

The pronounced puritan moral compass that steered Amy away from the sins of the flesh also empowered her to pass judgment on the “black widow,” Baroness Olga von Meyendorff. “This haughty countess has always had a great fascination for me, because she looks like a woman who ‘has a history.’ I have often seen her at Liszt’s matinees, and from what I hear of her, she is such a type of woman as I suppose only exists in Europe. She makes an impression of icy coldness and at the same time of tropical heat; the pride of Lucifer to the world in general!” Olga had been the wife of the Russian ambassador to the Court of Weimar, but he unexpectedly died after less than a year in office. Olga quickly found refuge in Liszt’s arms and for the next sixteen years they frequently traveled together. Liszt’s daughter Cosima described Olga as “unfortunately very unpleasant, disdainful and arrogant,” but Franz found her entirely fascinating and wrote no less than 400 letters to her. Since he was already a tonsured monk in the Franciscan order, it is hardly surprising that he destroyed almost all letters from her.

Olga von Meyendorff

Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous sobriquet, “Liszt, or the art of running after women” is not entirely accurate. For one, Liszt never had the need to run after women because women were constantly running after him. In addition, virtuosity on the keyboard and in the sack became indispensable parts of his performance persona. But this conscious construct of a public personality also created uncertainty; Franz was never sure that he was, in fact, truly loved. This might also explain his flight into the monk’s robe, because surely God knew for certain where the real Franz was hiding! In his relationships with women–excepting Marie d’Agoult — Franz was kind, gentle and extremely generous, yet real happiness and contentment was not to be found. In the end, the only person Franz ever really loved, was the reflection of himself he had created. Narcissus would have been very proud!