Haydn's skull

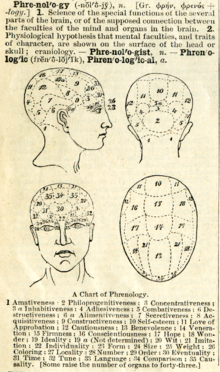

In order to more intimately understand criminal behavior, Peter had become an amateur phrenologist. His prisons were full of suitable subjects, however, in order to advance the theory, he needed to compare his findings with a subject that had exhibited great genius during his lifetime. The recent occupation of the Austrian capital by Napoleonic troops, which had forced the Habsburg Emperor to flee the city, finally gave Peter the opportunity to conduct his experiment. On 31 May 1809 Europe’s most famous and revered composer, Joseph Haydn quietly passed away in the Viennese district of Gumpendorf. Raging battles and all, it took over two weeks before his body was interred in the Hundsturm cemetery with both French and Austrian officials attending.

Face it, you couldn’t get more genius than Joseph Haydn, and Superintendent Peter saw his chance. Together with Joseph Carl Rosenbaum, a former secretary of Haydn’s employer Prince Esterházy, Peter bribed the sexton and returned to the graveyard on the evening of 17 June. That night, they exhumed Haydn’s body and hacked off his head. The ensuing phrenological examination revealed that Haydn’s skull — in full agreement with Gall’s chart — displayed a fully formed “bump of music.” Having independently verified Gall’s theories, Haydn’s head was stripped of flesh and muscle, and his brain removed. In turn, the cleaned skull was placed in a wooden box and catalogued for Peter’s personal collection. We might never have known about this lurid case of skullduggery if Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II had not insisted on giving Joseph Haydn a proper funeral in 1820. But when the Prince made plans to have Haydn’s remains transferred to the family seat in Eisenstadt, he discovered that the head was missing. The Prince was outraged, and the guilty parties quickly identified. Yet Peter and Rosenbaum had no intention of giving up the skull, so Rosenbaum purchased a substitute skull from a mortician, which was given to the authorities for authentication. During examination, the forged skull was found to be of a man much too young to have been Haydn. Peter apologized for the blunder, and immediately bought the skull of a much older man, which satisfied the doctors. It was declared the genuine article and buried with Haydn’s body.

Face it, you couldn’t get more genius than Joseph Haydn, and Superintendent Peter saw his chance. Together with Joseph Carl Rosenbaum, a former secretary of Haydn’s employer Prince Esterházy, Peter bribed the sexton and returned to the graveyard on the evening of 17 June. That night, they exhumed Haydn’s body and hacked off his head. The ensuing phrenological examination revealed that Haydn’s skull — in full agreement with Gall’s chart — displayed a fully formed “bump of music.” Having independently verified Gall’s theories, Haydn’s head was stripped of flesh and muscle, and his brain removed. In turn, the cleaned skull was placed in a wooden box and catalogued for Peter’s personal collection. We might never have known about this lurid case of skullduggery if Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II had not insisted on giving Joseph Haydn a proper funeral in 1820. But when the Prince made plans to have Haydn’s remains transferred to the family seat in Eisenstadt, he discovered that the head was missing. The Prince was outraged, and the guilty parties quickly identified. Yet Peter and Rosenbaum had no intention of giving up the skull, so Rosenbaum purchased a substitute skull from a mortician, which was given to the authorities for authentication. During examination, the forged skull was found to be of a man much too young to have been Haydn. Peter apologized for the blunder, and immediately bought the skull of a much older man, which satisfied the doctors. It was declared the genuine article and buried with Haydn’s body.

Bergkirche in Eisenstadt