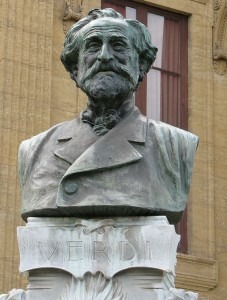

Verdi

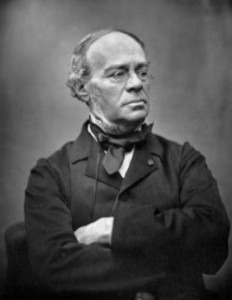

One of the most fascinating phenomena of the nineteenth century, it arose in Paris in an age marked by the spirit of technology and industrial enterprise. William Crosten rightfully suggested that “we must consider among the creators of these species not only Scribe, Meyerbeer, and Duponchel — the librettist, the composer and the scene designer — but also Louis Véron, the impresario of the Académie Royale de Musique, with his astonishingly precise vision of success.” Among the cornerstones of this repertory was the opera La Juive (The Jewess), composed by Fromental Halévy to a libretto by Eugène Scribe in 1835.

Fromental Halévy: La Juive, “Rachel, quand du Seigneur”

The story of an impossible love between a Christian man and a Jewish woman — set against the historical background of the Council of Constance of 1414 — became one of the most popular and admired operas of the 19th century. Gustav Mahler wrote, “I am absolutely overwhelmed by this wonderful, majestic work. I regard it as one of the greatest operas ever created.” And even Richard Wagner, who had only nasty things to say about Meyerbeer, wrote an enthusiastic review of La Juive for the German Press in 1841.

Robert le diable

Giuseppe Verdi: Don Carlos, Act 3

Per me giunto e il di supremo

Che parli tu di morte?

O Carlo, ascolta, la madre …

Premiered in 1867, Verdi revised this opera about the forbidden romance between the Spanish Infante, Don Carlos, and his stepmother, Queen Elisabetta de Valois, over the next twenty years. He made numerous cuts and composed various additions, resulting in a number of versions available to directors and conductors. Be that as it may, Verdi also applied his dramatic talents to the composition of a mid-life Requiem Mass. He famously remarked, “I am no longer just a clown serving the audience; beating a huge drum and shouting, Come on! Come on!” This musical mid-life crisis uses the Latin text of the Requiem mass like the libretto of an opera. “The music abounds with a dramatic passion different from and beyond its religious meaning, and the chorus seems mostly to represent the fearful and lamenting souls of the dead, while the soloists watch the dying process and plead for mercy and release from death.”

Fromental Halévy

In his personal life, Verdi disliked all forms of religiosity. This aspect is evident in the Requiem, as most movements are “more easily appreciated as inspired by psychological drama rather than religious fervor.” Nevertheless, the work was a huge success and performed in opera houses, churches and concert halls throughout Europe and America. It was once given, to Verdi’s horror, in the football stadium of the town of Ferrara, accompanied by a marching band. In 1897 Verdi gave his lover Teresa Stolz the autographed score of the Requiem Mass, inscribed to her as “the first interpreter of this composition.” Love conquers all! When the production of Aida was delayed due to a sudden illness of Stolz, Verdi used his free time to compose a String Quartet. He informed a friend, “I’ve written a Quartet in my leisure moments in Naples. I had it performed one evening in my house, without attaching the least importance to it and without inviting anyone in particular. Only the seven or eight persons who usually come to visit me were present. I don’t know whether the Quartet is beautiful or ugly, but I do know that it’s a Quartet.”

Giuseppe Verdi: String Quartet

Verdi, at least partially, modified his opinion in 1878. “I did not want to attach any importance to that work of mine, because I thought and still think (though I may be wrong) that the String Quartet in Italy is a plant growing in the wrong climate.” Somewhat surprisingly, Verdi did not rate very high as a composer immediately following his death. Only a handful of his works was considered worthy of serious study. It was Franz Werfel’s novel Verdi: The Novel of Opera, published in 1924 that finally considered him in the same breath as Richard Wagner. It was only in the 1970’s, however, that repeated performances in New York brought scholarly reappraisal and renewed popular enthusiasm. This enthusiasm continues unabated into the 21st century, and surely beyond. Viva Verdi!