Elena Langer

In April 2019, the world premiere of her new opera Beauty and Sadness will take place at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts in Hong Kong. The story comes from the last published novel of Japanese writer Yasunari Kawabata, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to (Beauty and Sadness) (1964). Oki, a writer, would like to be reunited with a lover, Otoko, from his past. He’s going to Kyoto to try to recreate that past as he has realized, years later, that she was the love of his life. Otoko is now a famous artist, living with her student and protégée, Keiko. Keiko, seeking to avenge Otoko for her abandonment by Oki, plans to seduce Oki’s son, Taichiro, and beauty and sadness have their place together.

The story is one of past memories and current jealousy, tradition and modernity, and the varieties of love and hate. Of the five characters in the opera, one, Oki, the writer, is not only a non-singing role but also a non-speaking role. His words and thoughts are ‘spoken’ by the cello.

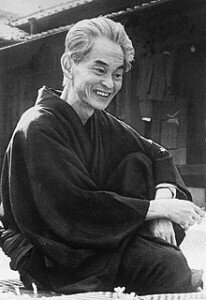

Yasunari Kawabata

© Wikipedia

One of the important parts of creating the Japanese milieu was the use of distinctive Japanese instruments. A large Taiko drum is placed on the stage and, in the orchestra, the Japanese end-blown flute, the shakhuhachi is used for its very romantic sound. The yang qin, a plucked zither, is also used for its timbre. Other unusual instruments include a bass guitar and the ethereal celesta. Langer sets her characters by instrumental timbre, much as Handel did, rather than in the Wagnerian manner of setting them individual themes. When we asked how she wrote for these traditionally non-notated instruments, she spoke of the care she took for each instrument and player. For the Taiko drum, for example, she created a notation that told the player when to start, when to stop, and what mood was to be conveyed – the notation was tailor-made for the instrument and its player.

To get an idea of Langer’s use of timbre, the interplay between the voices and the instruments in her 2013 work Landscape with Three People, setting the poetry of Lee Horwood, is a good guide. The close match in the two singer’s voices, paired with the oboe and the strings makes a close-textured sound.

Langer: Landscape with Three People (Anna Dennis, soprano; William Towers, counter-tenor; Nicholas Daniel, oboe; Roman Mints, violin; Meghan Cassidy, viola; Kristina Blaumane, cello; Robert Howarth, organ)

Next step for the opera is a dreamed-of trip to Japan, taking the text back home, as it were.

We asked Langer about her spare time and she said walking and swimming were her delights, as Hampstead Heath were readily available. In fact, the water music used at the end of the opera came to her while swimming in the Kenwood Ladies’ Pond on Hampstead Heath. Beyond all that, it’s music that she loves best and being in London gives her access to a world of music.