Selling music in the Renaissance wasn’t that different from selling music today. Published music needed a way to differentiate itself from other, similar pieces of music. The title pages tended to look alike: Name, composers’ name (maybe), patron, voice part, and publisher’s name, all in fairly repetitive format. The music was mostly printed oblong. As publishers became more certain of their markets, they started to put images on the title pages that would identify the work without having to read through all the text:

Selling music in the Renaissance wasn’t that different from selling music today. Published music needed a way to differentiate itself from other, similar pieces of music. The title pages tended to look alike: Name, composers’ name (maybe), patron, voice part, and publisher’s name, all in fairly repetitive format. The music was mostly printed oblong. As publishers became more certain of their markets, they started to put images on the title pages that would identify the work without having to read through all the text:

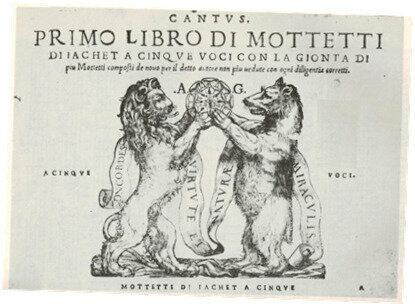

The leading publisher in Venice from the mid sixteenth century, the publisher Antonio Gardano used an image created from his patron’s name to indicate his company. His patron, Leoni Orsini (or Mr. Lion Bear) shows up in Gardano’s printer’s mark as a Lion and a Bear (in a rather stylized manner).

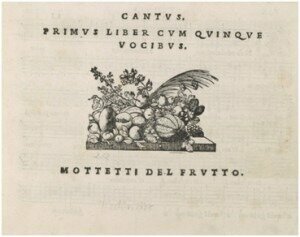

Another way of selling your music was to put it together in a collection – The Fruit Collection or the Muse Collection. Beginning in September 1538, Gardano started a series of motet books that he marketed as the “Motetti del Frutto,” with a luscious basket of fruit replacing the lion and the bear on his title page:

Another way of selling your music was to put it together in a collection – The Fruit Collection or the Muse Collection. Beginning in September 1538, Gardano started a series of motet books that he marketed as the “Motetti del Frutto,” with a luscious basket of fruit replacing the lion and the bear on his title page:

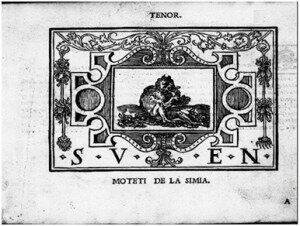

The design is very simple and would have been distinctive. However, in January 1539, a publisher in Ferrara began a new motet series , the “Motetti de la Simia”, or the Monkey Motets, using an image of a monkey with fruit scattered all around him:

Detail:

Detail:

So now the question arises: is this monkey eating the fruit “gathered” by Gardano for his Motetti del Frutto? Does the fact that Gardano’s shop in Venice was on the Ca’ de Simia (Monkey Street) have any bearing here? It would appear that the Ferrarese publishers, Buglhat, Campis and Hucher, had been able to steal from Gardano the motets that they printed in their Monkey Motet books – not only did they publish the same composers but also they published motets in the new imitative style that Gardao was showcasing in his Fruit series. They created their title page so that they could make fun of Gardano and show that they had been able to publish the motets that he considered his.

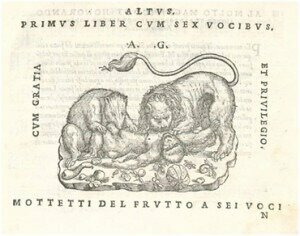

Gardano’s reaction is priceless. In this time before copyrights, there was nothing he could do to the Ferrarese publishers – the music was lost and he couldn’t publish it. He could however, take his own revenge in print for their transgression.

Gardano’s reaction is priceless. In this time before copyrights, there was nothing he could do to the Ferrarese publishers – the music was lost and he couldn’t publish it. He could however, take his own revenge in print for their transgression.

In the next Motetti del Frutto book, which appeared later in 1539, some of the part books show his lion and bear eating a monkey, with the disputed fruit scattered around. The preface to the book speaks of the vigilance of the ferocious lion and cruel bear against the thieving monkey:

And so Gardano saw off the Monkey motets – no more were published and the Ferrarese publishers themselves soon went out of business. This commercial competition was discovered by the musicologist Mary S. Lewis as she was preparing her monumental work on Gardano as publisher.

And so Gardano saw off the Monkey motets – no more were published and the Ferrarese publishers themselves soon went out of business. This commercial competition was discovered by the musicologist Mary S. Lewis as she was preparing her monumental work on Gardano as publisher.

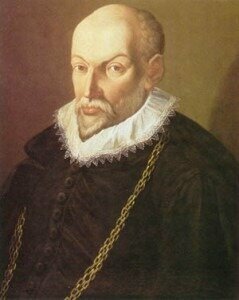

The predominant composer in Gardano’s Fruit series was Nicolas Gombert (1495-1560). Although now his name is not widely known, at the time, he was the leading composer of his time, bridging the early Renaissance writing of Josquin and the high Renaissance style of Palestrina. He served for much of his life at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

Nicolas Gombert

In illo tempore

More of Gombert’s works, both sacred and secular, can be heard on this collection of his sacred and secular music.

Salve regina (alternatim)

Je suis trop jonette (a 3)

Ave Maria (a 5)