Credit: http://bachtrack.com/

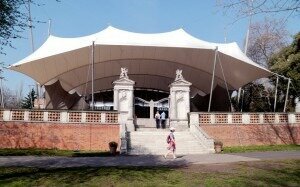

The company has a new innovation to be proud of – it is the first British opera company to support the work of Vocal Eyes, a UK audio description charity that provides access to the arts for the blind and partially sighted. Founded in 1998, Vocal Eyes has collaborated with many arts organisations in the UK, especially in theatre – they celebrated their 10th birthday with over 160 blind people watching Les Misérables on the West End, a Guinness World Record – but this summer they entered the opera house for the first time to visually describe a performance of Rossini’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia at Opera Holland Park in London. I went along to explore.

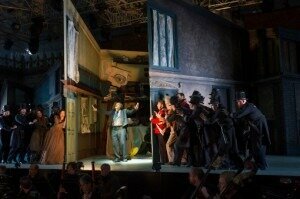

I was quickly struck by how unobtrusive the description was. There was just a simple earpiece for those who needed it; my expectations of plot descriptions shouted over Rossini’s music or visual gags explained blow-by-blow could not have been further from the mark. There were also long periods of no description, so that enjoyment of the music was not hindered. And there was certainly much to enjoy – the show was surely stolen by Kitty Whately’s Rosina, her superb coloratura and glorious even tone bringing many sides to this character. But I was thrilled by superb performances from the whole cast, including the chorus; it was an object lesson in opera’s power to move and excite even without a ‘concept’ (the production was in 19th century dress). The City of London Sinfonia played with great energy under the direction of Matthew Waldren, with a remarkable range of different colours on show, especially in the Act II storm – truly unsettling in this production.

Credit: http://i.telegraph.co.uk/

It is also worth remembering that the audio description surely cannot communicate much of an opera’s production, its staging, scenery, costumes and so on. The fact that these performances are still enjoyed by audiences should send a clear message to opera houses about their audiences’ real priorities; as in this production, it is the singing and playing rather than the director’s ideas that give the greatest effect.

We musicians often think of our hearing as perhaps our most vital sense; the image of the deaf Beethoven hammering his piano in order to hear his late music has become an archetype of the suffering Romantic artist. Yet blindness has also affected musicians. Frederick Delius dictated his last works to his amanuensis Eric Fenby, and Handel was essentially blind by the end of his life; in his final oratorio Jephtha the chorus ‘How dark, O Lord, are thy decrees’ has been interpreted as representing Handel’s desperation at his developing condition. Vocal Eyes undertakes vital work in opening up art forms of many kinds, not just classical music and opera, to blind people from all walks of life. As they say themselves, ‘Access to the arts is not about political correctness; it’s about quality of life’; do support them if you can.

Official Website