In my last article, ‘Visions of Arcadia in Music, Art and Literature I’, I focused on the Arcadian theme in the classical period. Today I will concentrate on its continuation in the 19th century — with the music of Jacques Offenbach and Claude Debussy, the paintings of Paul Cézanne and the poems of Charles Baudelaire.

In my last article, ‘Visions of Arcadia in Music, Art and Literature I’, I focused on the Arcadian theme in the classical period. Today I will concentrate on its continuation in the 19th century — with the music of Jacques Offenbach and Claude Debussy, the paintings of Paul Cézanne and the poems of Charles Baudelaire.

Jacques Offenbach’s 1860 operetta ‘Daphnis and Chloe’ is based on a Greek novel from the 2nd century A.D. In 1559, this novel had been translated into the better-known French version by Jacques Aymot. Its theme was also taken up by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century, in a work still unfinished at the time of his death. Many sculptors and painters throughout the centuries were inspired by this story, whose setting, like Offenbach’s operetta, is the island of Lesbos in ancient Greece. Daphnis and Chloe had been orphaned and were raised by two shepherds. They fall in love. Pan, with his flute and seductive music, tries to thwart them, but is unsuccessful and the lovers are united at the end. Later, in the beginning of the 20th century, Offenbach’s operetta became the inspiration for the ballet ‘Daphnis et Chloé’ — the score by Maurice Ravel and the choreography by Michel Fokine for the Ballets Russes.

Maurice Ravel

Daphnis et Chloe

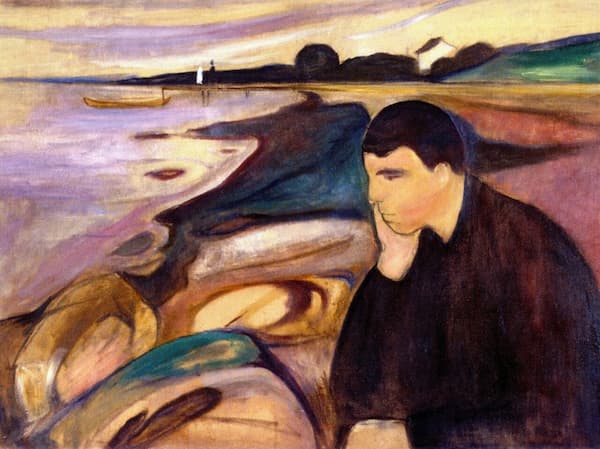

The Arcadian theme of satyrs and nymphs also was the inspiration for Debussy’s composition, ‘Prélude à L’Après-Midi d’un Faune’ (Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun) — based on a beautiful poem by his close friend, Stéphane Mallarmé. Debussy’s haunting melody, where reality and dream are interchangeable, uses non-functional harmonies, with the disappearance of texture and structure, where note combinations exist for their own sake and where color is more important than content. Debussy’s composition was also taken up by the Ballets Russes, with the great Nijinsky dancing the role of the faun.

The Arcadian theme of satyrs and nymphs also was the inspiration for Debussy’s composition, ‘Prélude à L’Après-Midi d’un Faune’ (Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun) — based on a beautiful poem by his close friend, Stéphane Mallarmé. Debussy’s haunting melody, where reality and dream are interchangeable, uses non-functional harmonies, with the disappearance of texture and structure, where note combinations exist for their own sake and where color is more important than content. Debussy’s composition was also taken up by the Ballets Russes, with the great Nijinsky dancing the role of the faun.

Claude Debussy

Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune

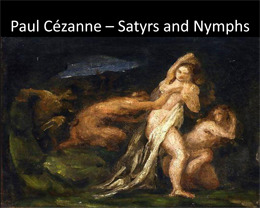

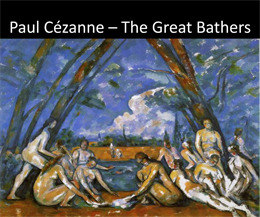

Arcadian themes in painting continued from the classical period well into the 19th century based on the continued interest in Virgil’s ‘Eclogues’. Paul Cézanne, an excellent student of Latin and Greek, had personally translated Virgil’s second ‘Eclogue’, which he sent to his childhood friend, Emile Zola, in Paris. Many of Cézanne’s early paintings show satyrs, nymphs and subjects of Greek mythology, such as ‘The Judgment of Paris’, ‘Satyrs and Nymphs’ as well as the many paintings of bathers in bucolic settings.

One of his poems to Zola reads:

One of his poems to Zola reads:

“To sing to you of some forest nymph

My voice is not sweet enough

And the beauties of the countryside

Whistle at those lines in my song

That are not humble enough” (pp. 164, Exhibition catalogue, Philadelphia Museum of

Art, 2012)

Cézanne considered the neo-classical painter, Nicolas Poussin (mentioned in my previous article), as his inspiration, but as Cézanne would always proclaim, he would “refaire Poussin d’après la nature” (“re-do Poussin after nature”). Another of Cézanne’s childhood friends, the writer Joachim Gasquet (whom he also painted later on), had sent him a book of his poems, entitled “Les Chants Séculaires” which mentions Poussin — “Poussin, when I think of you, I see Arcadia once more”, and continues with the following verse:

‘And that, to awaken our land that sleeps,

Under these trees bathed in an austere dream

You painted the shepherd of a new golden age.

Oh, the most noble ideal, lost Arcadia’ (pp. 166, Exhibition catalogue, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2012).

Many of Cézanne’s paintings of the ‘Bathers’ show them in a very structured setting, i.e. with visible brushstrokes, applied in the same direction, situating the bathers structurally between the trunks of the trees, but using lighter impressionistic colors which seem then to diffuse the various forms.

Cézanne’s attempt to re-fashion classicism, to modernize this ancient dream, is echoed in the works of Gauguin and Matisse, and later in the 20th century, in the works of the German Expressionist painters.

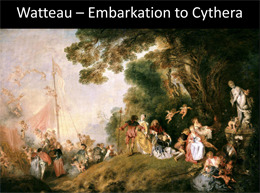

In poetry, Charles Baudelaire — in his pursuit of the ‘ideal’, often interrupted by periods of the ‘spleen’, i.e., the reality of everyday life, which weighed on him — tried to recapture his ideal of the ‘lost Arcadia’ in his poems such as ‘L’Invitation au Voyage’ (Invitation to a Journey), which recalls a painting by Watteau ‘L’Embarquement vers Cythère’ (The Embarkation to Cythera):

| ‘Mon enfant, ma soeur, Songe à la douceur D’aller là-bas vivre ensemble! Aimer à loisir, Aimer et mourir…. Là, tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté, Luxe, calme et volupté’. | ‘My child, my sister, Think of the sweetness To go there to live together! To love a leisure, To love and die…. There, all is but order and beauty Luxury, calm and voluptuousness’. |

In their own way, each of these artists kept searching for the Arcadian past in the modern world – a quest which will be the continued focus of my next article.