In my last article ‘Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Frederick the Great and the Architecture of the Rococo’ I focused on the re-emergence of pastoral themes in music and the arts. Members of the aristocracy, dressed as shepherdesses and shepherds appeared in many paintings of the period, pursuing romantic pursuits in bucolic settings, which then also found its echo in the music of the period. Today, I would like to take this theme further by placing it into a more historical context, i.e., the context of Arcadia, which had been the subject of a recent inspiring exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, titled ‘Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse’ — Visions of Arcadia’ — there, focused mainly on the relationship between painting and literature; here, extending the connection to music as well.

In my last article ‘Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Frederick the Great and the Architecture of the Rococo’ I focused on the re-emergence of pastoral themes in music and the arts. Members of the aristocracy, dressed as shepherdesses and shepherds appeared in many paintings of the period, pursuing romantic pursuits in bucolic settings, which then also found its echo in the music of the period. Today, I would like to take this theme further by placing it into a more historical context, i.e., the context of Arcadia, which had been the subject of a recent inspiring exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, titled ‘Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse’ — Visions of Arcadia’ — there, focused mainly on the relationship between painting and literature; here, extending the connection to music as well.

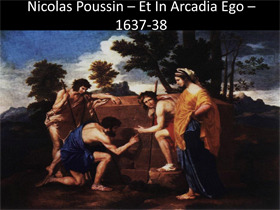

Arcadia, Greek province and Pan’s homeland, the idyllic paradise of the so-called ‘Golden Age’, a mythic place of beauty and repose in which man lives in harmony with nature, has been a popular artistic subject in the visual arts and literature throughout the ages. In particular, it saw a revival in the 1st century BC with Virgil’s ‘Eclogues’ (cited in the catalogue of the exhibition, p. 14), which had a profound influence on Western literature and the arts from Renaissance times onward throughout the centuries. Its influence extended even to our own time, for example, in Evelyn Waugh’s ‘Brideshead Revisited’ (1945), with the first part of his novel subtitled ‘Et in Arcadia ego’ — the same title as the painting by Nicolas Poussin, ‘Et in Arcadia ego/Even in Arcadia, there I am’ – – as well as in Tom Stoppard’s play ‘Arcadia’, initially also subtitled ‘Et in Arcadia ego’.

It is noted that in the 16th century, the Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano named North America’s unspoiled wilderness ‘Arcadia’ – – the name still exists today as Arcadia National Park in Maine.

It is noted that in the 16th century, the Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano named North America’s unspoiled wilderness ‘Arcadia’ – – the name still exists today as Arcadia National Park in Maine.

As Virgil wrote:

YET YOU, ARCADIANS WILL SING

THIS TALE TO YOUR MOUNTAINS;

ARCADIANS ONLY KNOW HOW TO SING

HOW SOFTLY THEN WOULD MY BONES REPOSE,

IF IN YOUR OTHER DAYS YOUR PIPES SHOULD TELL MY LOVE!

AND OH THAT I HAD BEEN ONE OF YOU,

THE SHEPHERD OF A FLOCK OF YOURS,

OR THE DRESSER OF YOUR RIPENED GRAPES! …

HERE ARE COLD SPRINGS, LYCORIS,

HERE SOFT MEADOWS, HERE WOODLAND;

HERE WITH YOU, ONLY THE PASSAGE OF

TIME WOULD WEAR ME AWAY.

Virgil, Eclogues 10:31-36, 42-43

Monteverdi: L’Orfeo

Monteverdi: L’Orfeo

Renaissance painters and poets continually used the images of idyllic settings in their works, such as Giorgione in his 1509 painting ‘Pastoral Concert’, currently in the Louvre in Paris (now attributed in part to Titian). The reference to music in this painting is important, not just in its depiction of musical instruments, but also in the actual participation of the various figures in music making. The bucolic setting, the shepherd with his flock in the distance, the figures dressed in classical Greek robes, all contribute to re-create a peaceful, pastoral scene — the image of Arcadia. In the Homeric tradition, shepherds often play the syrinx, or Pan flute, considered the quintessential pastoral instrument. In Italy, the tradition of the pastoral poetry (Virgil’s Eclogues were performed as sung mime in the 1st century) led to ‘pastourelle’, sung by the troubadours (still in existence today in a form of Italian folksong), leading to the cantata and serenata and to Italian opera, such as Peri’s ‘Dafne’ and Monteverdi’s ‘L’Orfeo’.

In Renaissance England, Shakespeare also uses Arcadian settings for his plays, in particular in ‘As You like It’ and ‘The Winter’s Tale’, in which Act 4, Scene 4 can be considered a lengthy pastoral digression.

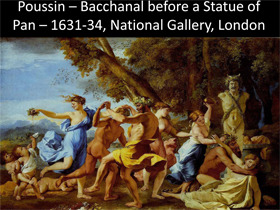

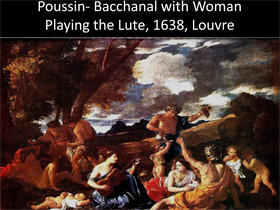

In 17th century France, Nicolas Poussin’s paintings ‘Et in Arcardia Ego, The Bacchanal before a Statue of Pan and Bacchanal and a Woman playing the Lute’ not only continued the pastoral tradition, but became a formative influence for his contemporaries in literature (Racine and Corneille) and art, with many of the painters of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, such as Watteau, Fragonard, Cézanne, Gauguin, Matisse and the German Expressionists transforming pastoral settings. His ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ is testament to the classical harmony of order and balance, with the figures of the shepherds enclosed in the classical triangle, set in a beautiful landscape. Poussin’s two other paintings of the Bacchanals express another aspect of Arcadia which would later be taken up by many artists in the late 19th and 20th centuries, with the figures of Dionysos and his drunken companion Selenius, satyrs, fauns and nymphs. They add a dimension of disorder, of the instinctual and sexual – – elements of what Baudelaire expressed in his poetry, the ‘dérèglement des sens’ – – the dissoluteness of the senses.

In 17th century France, Nicolas Poussin’s paintings ‘Et in Arcardia Ego, The Bacchanal before a Statue of Pan and Bacchanal and a Woman playing the Lute’ not only continued the pastoral tradition, but became a formative influence for his contemporaries in literature (Racine and Corneille) and art, with many of the painters of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, such as Watteau, Fragonard, Cézanne, Gauguin, Matisse and the German Expressionists transforming pastoral settings. His ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ is testament to the classical harmony of order and balance, with the figures of the shepherds enclosed in the classical triangle, set in a beautiful landscape. Poussin’s two other paintings of the Bacchanals express another aspect of Arcadia which would later be taken up by many artists in the late 19th and 20th centuries, with the figures of Dionysos and his drunken companion Selenius, satyrs, fauns and nymphs. They add a dimension of disorder, of the instinctual and sexual – – elements of what Baudelaire expressed in his poetry, the ‘dérèglement des sens’ – – the dissoluteness of the senses.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68, “Pastoral”

Händel: Acis and Galatea, HWV 49

In the music of the 18th century, Arcadia and the pastoral find expression in Händel’s ‘Acis and Galatea’, Rousseau’s ‘Le Devin du Village’ and, of course, in Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, the famous ‘Pastorale’, which he considered an expression more of feeling than of realistic imagery — an aspect of music which would become increasingly important during the Romantic period.

The focus of my next article will be following the Arcadian pastoral theme in music, art and literature in the 19th and 20th centuries. Stay tuned…

More Arts

-

Musicians and Artists: Greenbaum and Escher Discover how Escher's visual paradoxes inspired Australian composer Greenbaum

Musicians and Artists: Greenbaum and Escher Discover how Escher's visual paradoxes inspired Australian composer Greenbaum -

Musicians and Artists: Schurmann and Bacon Inspirations behind Gerard Schurmann’s 6 Studies of Francis Bacon

Musicians and Artists: Schurmann and Bacon Inspirations behind Gerard Schurmann’s 6 Studies of Francis Bacon -

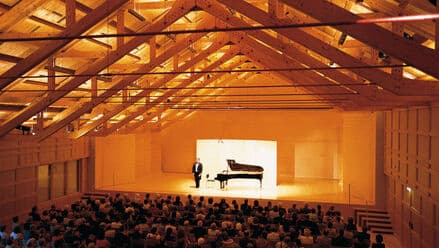

The Art of the Concert Hall: Angelika Kauffmann Hall in Schwarzenberg When a painter's legacy creates perfect acoustics!

The Art of the Concert Hall: Angelika Kauffmann Hall in Schwarzenberg When a painter's legacy creates perfect acoustics! -

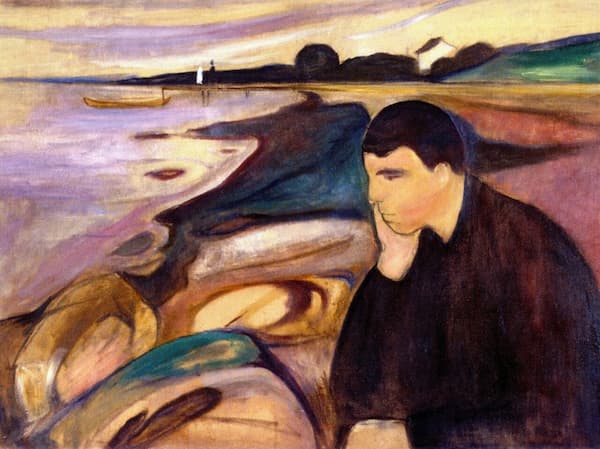

Musicians and Artists: Frances-Hoad and Munch Find out how Munch's Melancholy inspires Frances-Hoad's Piano Trio

Musicians and Artists: Frances-Hoad and Munch Find out how Munch's Melancholy inspires Frances-Hoad's Piano Trio