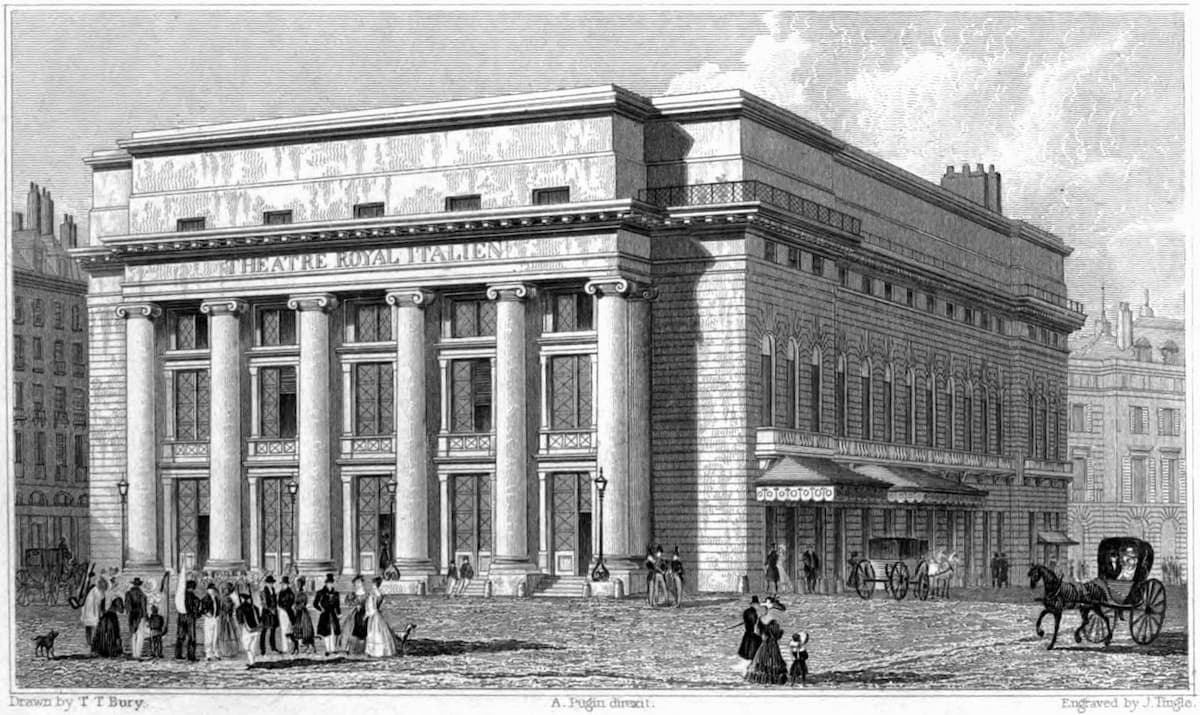

One of the biggest dangers to the wellbeing of operatic theatres throughout history has been fire! As one critic rightly said, “Scenery, stucco, seats and curtains were all highly inflammable. Add to those the wooden structure of the building and you have the perfect material for an inferno.” And if you think of it, it only took one misplaced candle to set the old wooden structures alight. So the Bayerische Statsoper in Munich came up with an ingenious plan and installed an early prototype of sprinkler system. Regrettably, the winter of 1823 was one of the coldest in history, and when the water tanks on top of the theatre froze solid, the building went up in flames. The Milan theatre burned in 1776 and 1943, Montepellier 1785 and 1881, the Opera Comique in Paris in 1838 and 1887, the Bolshoi in Moscow in 1853, and the Teatro Lyrico in Madrid in 1909. The list goes on and on and does not even include damage and fire inflicted by war, like it happened in Dresden, Berlin, Valetta, Munich and Vienna. The 20th century gave up candles for lighting and attempted to make the buildings fireproof, but it only took one spark for the Liceu in Barcelona to burst into flames in 1994.

One of the biggest dangers to the wellbeing of operatic theatres throughout history has been fire! As one critic rightly said, “Scenery, stucco, seats and curtains were all highly inflammable. Add to those the wooden structure of the building and you have the perfect material for an inferno.” And if you think of it, it only took one misplaced candle to set the old wooden structures alight. So the Bayerische Statsoper in Munich came up with an ingenious plan and installed an early prototype of sprinkler system. Regrettably, the winter of 1823 was one of the coldest in history, and when the water tanks on top of the theatre froze solid, the building went up in flames. The Milan theatre burned in 1776 and 1943, Montepellier 1785 and 1881, the Opera Comique in Paris in 1838 and 1887, the Bolshoi in Moscow in 1853, and the Teatro Lyrico in Madrid in 1909. The list goes on and on and does not even include damage and fire inflicted by war, like it happened in Dresden, Berlin, Valetta, Munich and Vienna. The 20th century gave up candles for lighting and attempted to make the buildings fireproof, but it only took one spark for the Liceu in Barcelona to burst into flames in 1994.

Fires, wars and bombs are one thing, but since operatic theatres tend to generate a good deal of money, the biggest dangers to these venerable structures are politicians, bureaucrats and organized crime! You may have seen the movie The Godfather: Part III, with the assassination of Michael Corleone’s daughter supposedly staged in the Teatro Giuseppe Verdi in Palermo, Sicily. Unfortunately, when Francis Ford Coppola was shooting his film, “Il Massimo” as the theatre is locally known, had already been closed for 15 years! The closure of Italy’s largest theatre—it is actually the third largest opera house in Europe—was blamed on “megalomania, bureaucratic complications, administrative ineffectiveness and political corruption.” In other words, the Sicilian Mafia had gotten involved! It all goes back to the tumultuous post-war period after World War II. Huge areas of Palermo had been flattened by allied bombings and demand for housing went through the roof. Since much of this construction was subsidized by public money, it didn’t take long for the “Cosa Nostra” to take control of Palermo’s Office of Public Works. Stunningly, between 1959 and 1963, 80 percent of building permits were given to only 5 people closely working for the organization. Construction companies unconnected with the Mafia were forced to pay protection money. As such mafia organizations entirely controlled the building sector in Palermo, everything from quarries, site clearance firms, cement plants, and metal depots to wholesalers for sanitary fixtures.

Fires, wars and bombs are one thing, but since operatic theatres tend to generate a good deal of money, the biggest dangers to these venerable structures are politicians, bureaucrats and organized crime! You may have seen the movie The Godfather: Part III, with the assassination of Michael Corleone’s daughter supposedly staged in the Teatro Giuseppe Verdi in Palermo, Sicily. Unfortunately, when Francis Ford Coppola was shooting his film, “Il Massimo” as the theatre is locally known, had already been closed for 15 years! The closure of Italy’s largest theatre—it is actually the third largest opera house in Europe—was blamed on “megalomania, bureaucratic complications, administrative ineffectiveness and political corruption.” In other words, the Sicilian Mafia had gotten involved! It all goes back to the tumultuous post-war period after World War II. Huge areas of Palermo had been flattened by allied bombings and demand for housing went through the roof. Since much of this construction was subsidized by public money, it didn’t take long for the “Cosa Nostra” to take control of Palermo’s Office of Public Works. Stunningly, between 1959 and 1963, 80 percent of building permits were given to only 5 people closely working for the organization. Construction companies unconnected with the Mafia were forced to pay protection money. As such mafia organizations entirely controlled the building sector in Palermo, everything from quarries, site clearance firms, cement plants, and metal depots to wholesalers for sanitary fixtures.

In 1974, “Il Massimo” closed for a couple short weeks in order to update safety regulations and to modernize the electrical system. And that’s when things got interesting. Political infighting gave way to a bidding war and a number of quick assassinations. Rebuilding contracts were traded like playing cards, costs spiraled out of control, and politicians kept making promises. It all meant that the opera house remained closed for 23 years! Local superstition put the blame on the curse of a little nun, whose tomb had been violated during the initial construction of the theater, yet everybody knew the real culprits but were afraid to speak up. It took Leoluca Orlando, who was running for major of Palermo in November 1993, to finally put an end to this nonsense. The re-opening of the theatre was one of his campaign promises, and once he subtly introduced minute changes of legislation, the house was restored and reopened in 1998 “as an effective symbol of the renaissance of the town.” Yet after 23 years of neglect, the interior had completely deteriorated and all the frescoes, boxes and stage equipment needed to be replaced. So it took another 3 years and a substantial financial commitment for this grand theatre to come back to life. “Il Massimo,” however, does not hold the record for longest closure. That honor belongs to the Teatro Real in Madrid, a house that was closed for more than 60 years. Read all about that operatic disaster in our final instalment of this series.

Giuseppe Verdi: Falstaff, “Sul fil d’un soffio etesio”

You May Also Like

-

Operatic Disasters I We all remember that horrible night in 1996, when the Venetian opera house “La Fenice” was destroyed and gutted by fire.

Operatic Disasters I We all remember that horrible night in 1996, when the Venetian opera house “La Fenice” was destroyed and gutted by fire.

More Society

-

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia "It's really changed how we view music and what it can do for people"

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia "It's really changed how we view music and what it can do for people" -

Opéra-Comique at Salle Favart Discover the history and tragic fire of the official Théâtre de l'Opéra-Comique

Opéra-Comique at Salle Favart Discover the history and tragic fire of the official Théâtre de l'Opéra-Comique -

Cello Lament for The Sycamore Gap Tree Italian cellist and composer Riccardo Pes’ “Lament for the Tree”

Cello Lament for The Sycamore Gap Tree Italian cellist and composer Riccardo Pes’ “Lament for the Tree” -

The Gürzenich in Cologne Learn about some famous premieres here

The Gürzenich in Cologne Learn about some famous premieres here