Hilary Hahn

Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104, Weilerstein, Alisa Weilerstein

To help you avoid pain and to play with ease here is a survival guide.

1. Make sure your instrument is in good repair. It should respond easily and fit you. Avoid instruments that are too large for you, and bows that are too heavy. Upper strings: search for the right chin rest and shoulder pad fit; cellists lower your string height; woodwind players check for leaks; brass players start with less heavy and smaller instruments. Seek ergonomic solutions to any large reaches on your instrument.

2. Holding our instruments entails some awkward postures. Limit the time you spend on difficult passages especially in extreme positions. Don’t hold extensions, chords, or stretches, and avoid endless repetition. Some composers have written tremendously repetitive passages, or difficult techniques such as tremolo, (rapidly going back and forth with the bow) or long trill passages—Sibelius and Tchaikovsky works have pages of tremolo, and Shostakovich has written long passages of trills and repetition for strings and winds (watch 15 minutes and especially 22.22 into the Symphony No 11, “The Year 1905” below. At 25.45 the long pages of trills start). Practice these carefully and in smaller segments.

Shostakovich: Symphony No 11, 1905

3. Practice with intension. Troubleshoot by breaking down a passage to just a few notes to figure out how to play more fluidly. Don’t get stuck on a tough passage. Work on it and then come back to it later in the day. Analyze what might not be working: is it the fingering? A bowing or phrasing? Or where you are taking a breath? Make sure you are not grabbing, squeezing, or pressing with your fingers. A lighteningly fast technique, and shifting with ease, in the case of a string player, is achieved by releasing your fingers swiftly.

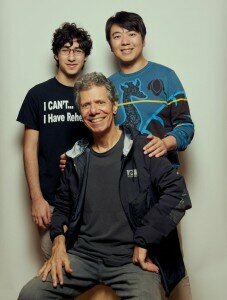

Mr. Lando and Mr. Lang, standing, with the jazz pianist Chick Corea, who is joining them for a rarely performed two-piano (and, in this case, five-hand) version of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” © Vincent Tullo for

The New York Times

5. Pay close attention to how you felt physically or emotionally after playing. It is helpful to keep a daily diary and ask yourself: Was a phrase more difficult to ‘nail’ today than last week? Did you feel stiff or tense or hot? Did you sense your fingers wouldn’t “do” what you wanted them to do? Most issues are cumulative and begin with fatigue or sluggishness. Never ignore pain. Should you feel pain or numbness, stop. The sooner you get help from a qualified healthcare provider the more likely a problem can be solved quickly.

6. Believe it or not, our brains learn just as well when we review the music without our instrument. Working on the music away from our instrument means less wear and tear on our bodies and ears. Spend time on memorization by singing the music or visualizing the notes on the page. Focus on phrasing, on the emotions you’d like to convey, on the concept of the whole piece. This is much easier to do when you’re not busy trying to produce the sound or perfect a difficult passage.

7. Vary your repertoire. A piece by Mozart will use different muscles and have different challenges than a Strauss work. And if you can, alternate between sitting and standing when you practice.

8. Monitor the number of contests, and concerts you say ‘yes’ to. It’s easy to get overscheduled. Be realistic about pieces you can play. It’s much more satisfying to play a piece within your abilities, and play it well, than struggling with a piece that is beyond your capacity. This is especially important for student and amateur musicians, and when choosing a recital program or audition repertoire. Avoid performing works that are totally new to you. Choose pieces that you’ve worked on and have had time to “put away”. When you return to them you will likely have much more ease and facility, as well as a fresh approach.

9. Silence that negative chatterbox in your head. Give yourself positive reinforcement. Meditation, or practicing yoga can reduce the additional stress you might be under. And remember to breathe deeply!

10. Take breaks. Although I mentioned this tip in the previous article, I can’t emphasize it enough. Physically and mentally your body has a limit. Shorter practice segments are more effective. In the months and years to come this approach will pay off. You’ll be able to continue making music for a long time.

Short excerpt of Lang Lang talking about Rhapsody and “borrowing” his student’s hand.