I have been thinking more about the relationship between music and memory (which I first explored in my previous article) in two different areas, which has led me to two brief comments. Firstly, the role that forgetting plays in improvisation, and, secondly, the role of remembering in ballet.

I have been thinking more about the relationship between music and memory (which I first explored in my previous article) in two different areas, which has led me to two brief comments. Firstly, the role that forgetting plays in improvisation, and, secondly, the role of remembering in ballet.

So, first, a quick comment on improvisation: improvisation is an exercise in learning to forget. As opposed to just playing randomly (which is what would happen if I were to sit at a piano today), improvisation requires a great deal of knowledge and technique. It requires them to be in-built in your memory, so that you actually remember what to play. But at the same time it requires the player to achieve a zen-like state of mind where he allows himself to forget the part he is supposed to interpret and just plays. This “conscious unconscious” opens the door to the Repetition which I have discussed before.

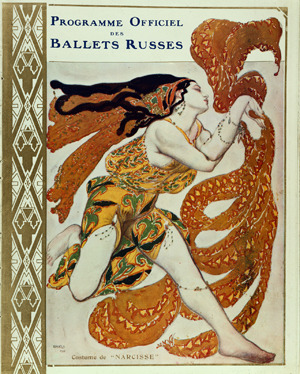

More importantly, I was very impressed by the reconstruction of old ballet performances I saw recently. Last week, taken by my ballerina, I attended two evenings of a ballet season in London called the Diaghilev Festival – Les Saisons Russes du XXI. This, organised by the Maris Liepa Foundation in the London Coliseum, was a re-creation of Serge Diaghilev’s famous Ballets Russes spectacles, presenting a series of ballets as they were supposed to be danced when they were created in the early decades of the twentieth century. The festival as a whole was fascinating: the dancing, by the Kremlin Ballet Company with some of the star dancers of the Bolshoi, was fantastic and the music, by the St Petersburg State Academy, excellent. Some of the ballets that made a bigger impression on me, because of the combination of music and rescued choreography, are worth discussing in more detail here.

In the first night I attended, The Firebird, with the amazing score by Stravinsky and choreography by Fokine, was phenomenal. The set was definitely more eastern than in other productions, invoking the central Asian roots of the tale. The combination made the audience feel as though taking part in a voyage.

The second night I attended (which was the last one of the festival) was even better. Two of the ballets were breath-taking. L’apres-midi d’un Faune (Nijinsky’s choreography to Debussy’s music) was beautiful. One could feel the tension and release the ballet afforded, as well as the controversy surrounding its opening night (to give it away, of course, would be unfair).

But it was a re-choreographed Le pavillon d’Armide that I thought was the most remarkable performance of the festival – the one that best represented the spirit of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The music, entrancing, is by Tcherepnin. The story by Theophile Gautier is familiar (Omphale: 1834), that of the young man spending the night in a strange castle and falling in love with a beautiful woman who, he realises the next morning, is a tapestry. However, the original choreography, by Fokine, is lost. So Jurijus Smoriginas (re-)created a ballet for it, directed by Andris Liepa. This was a beautiful combination of French baroque formalism and eastern sensuality. The symmetrical choreography of the corps de ballet, invoking the rigidity of the scenery, was very subtly broken by an exotic hand movement here or a leg vibration there, reflecting the conflict the central characters are in, between their passion and their incompatible realities.

It was this perspective – France’s culture and civilisation seen through the eyes of eastern Russians; and an appropriation and sophistication of that culture – that I felt best captured the spirit of the original Ballet Russes. As excellent as the other performances of the original choreographies were, it was, perhaps ironically, this “new” ballet that most gave me a sense of what Diaghilev’s group represented to the ballet and to European culture. This re-creation bridged the gap between the hundred-year old composition and my very contemporary thrill.

Related videos:

Stravinsky conducts Firebird

Rudolph Nureyev: L’apres-midi d’un Faune