Credit: http://www.jeunes-talents.org/

Like many young artists, Marillier took to music early, enjoying music classes at his school in France from the age of 4. ‘I started playing the cello and piano,’ he says, ‘when I was 8 I changed from the cello to violin, as my sister Juliette, who played it then and is now a luthier, had convinced me of the beauty of the violin’s sound. My parents, though not musicians, were music lovers, and in both my parents’ families there were musicians, such as a great-uncle who sang with Callas.’

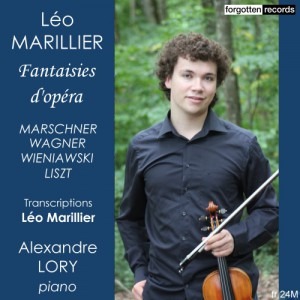

Marillier lists a sequence of early teachers who have been central to his development. ‘My first teacher Stefano Amara taught me about the passion of music, and my second teacher Larissa Kolos taught me the technique of violin playing. Alexis Galpérine was my first mentor, by which I mean a teacher whom you can engage in musical discussion – that’s basically what happened for the entire two years I studied with him as we worked on diverse repertoire, from Biber to Isang Yun, and shared some of our personal passions. I’m currently studying with Miriam Fried at the NEC in Boston, whose great awareness of the performing tradition has put my own interpretations into perspective.’ Marillier also mentions some less intensive but nevertheless significant relationships, including Stephane Tran Ngoc, Director of Strings at Royal College of London (‘I’m inspired by the personal involvement and stunning control of his playing’), and Wolfgang Marschner, whose Vampir variationen Marillier performs on his disc ‘Fantaisies d’Opéra’. ‘A friend of Hindemith, Marschner’s lifelong dedication to music and his wide range of knowledge is an example to me.’

Marillier has a range of significant achievements behind him, including recordings, solo appearances and competition success. He is clear, though, that he enjoys concerts ‘more than anything else’. He talks excitedly about collaborating with orchestras such as the Wiener Konzert-Verein and Klaipeda Orchestra, and also his love of chamber music, recalling a performance of the Chausson Concerto at the 40th Festival des Arcs – ‘it felt absolutely great flying through these textures’, he says, ‘but that of course wouldn’t have been possible without the other extraordinary musicians’. Another highlight is his success at the Tchaikovsky Competition for Young Musicians in Seoul; on winning the prize he says that felt ‘mixture of pride and humility that will stay in my memory for a long time.’

But far from being on a concert treadmill, Marillier thinks deeply about each performance. ‘I think of every performance as a way to make real the practice and heart I’ve put in for the preceding weeks,’ he says. ‘Music is not about playing as much repertoire as you can; it’s about feeling new things and making them clear to an audience.’ This sentiment is apparent in his thematically constructed programmes. One recital, for example, explores the Faust myth through music by Schumann, Schubert and Alkan, finishing with Marillier’s transcription of excerpt from Ligeti’s La Grande Macabre. Another recital, “Between the Compass and the Kaleidoscope”, follows the history of the sonata from Mozart to Schoenberg. ‘With programmes like these’, Marillier says, ‘I hope to awaken audiences to new themes in music, and to offer new things to those who are aware of the themes but not the pieces they inspired.’

But far from being on a concert treadmill, Marillier thinks deeply about each performance. ‘I think of every performance as a way to make real the practice and heart I’ve put in for the preceding weeks,’ he says. ‘Music is not about playing as much repertoire as you can; it’s about feeling new things and making them clear to an audience.’ This sentiment is apparent in his thematically constructed programmes. One recital, for example, explores the Faust myth through music by Schumann, Schubert and Alkan, finishing with Marillier’s transcription of excerpt from Ligeti’s La Grande Macabre. Another recital, “Between the Compass and the Kaleidoscope”, follows the history of the sonata from Mozart to Schoenberg. ‘With programmes like these’, Marillier says, ‘I hope to awaken audiences to new themes in music, and to offer new things to those who are aware of the themes but not the pieces they inspired.’ Marillier also enjoys the practice of transcription, once common amongst 19th century virtuosi. ‘The fact that I’ve “tasted” other major instruments like the cello and piano has encouraged me to be interested in “foreign” repertoires’, he says. So how do you compress large and complex scores for a violin? ‘Of course there are many decisions. I had to decide what Wagner to work on, as not all of his music can be transcribed successfully. Likewise not all of Liszt makes sense; some cuts are necessary, otherwise you would ruin the piece and insult Liszt! When you choose a piece to transcribe, you need to know that the way you want to play it somehow goes beyond what you’ve experienced by listening to it. You have to rethink the whole structure of the piece, to make it your own. I’m pretty sure many musicians are always transcribing, even composing in their head – it’s called daydreaming.’

A creative, thinking musician, Marillier is surely destined to become a major artist of our time. Nor is his focus or love of his work in question; when asked what he does outside of music, he answers simply: ‘Music is my life.’

Official Website