Franz Liszt

credit: http://americanlisztsociety.net/

Aix-en-Provence 27th December 2011

‘La Campanella’ is often heard as an encore at recitals, in TV commercials, and in movies. To some it is a perennial favourite, but to others it may be too frequently performed. In either case, it says something about the popularity of this piece which bears the names of two of the greatest instrumentalists in 19th century Europe, Paganini the violinist and Liszt the pianist. But what more do we know about this piece?

Liszt: Grande fantaisie di bravura sur La clochette de Paganini, Op. 2 (1834)

It is understood that a piano version of the piece first came into being after Liszt heard for the first time the wizardly Paganini perform his own second violin concerto in Paris in April 1832. So impressed was Liszt that, in a letter to his pupil Pierre-Etienne Wolff, he wrote, ‘Quel homme, quel violon, quel artiste! Dieu, que de souffrances, de misère, de tortures dans ces quatre cordes!’ (‘What a man, what a violin, what an artist! God, what suffering, what misery, what tortures in those four strings!’) At that time, Liszt was only 20 years old (Paganini was nearly 50).

The resultant piece was Liszt’s Op. 2, ‘Grande Fantaisie de Bravoura sur la Clochette de Paganini’ (‘La Clochette’ for short), dated 1834. It is fairly far removed from Paganini’s original concerto. It has an original introduction marked ‘excessivement lent’ (extremely slow) and many subsequent passages that are unpianistically loud (sempre ff to ffff) and fast (demi-semiquavers at prestissimo). The main theme and the variation à la Paganini contain some delightful moments, but much of the piece is not very playable or effective. Not surprisingly, it is relatively little known, not often recorded, and rarely performed in concerts.

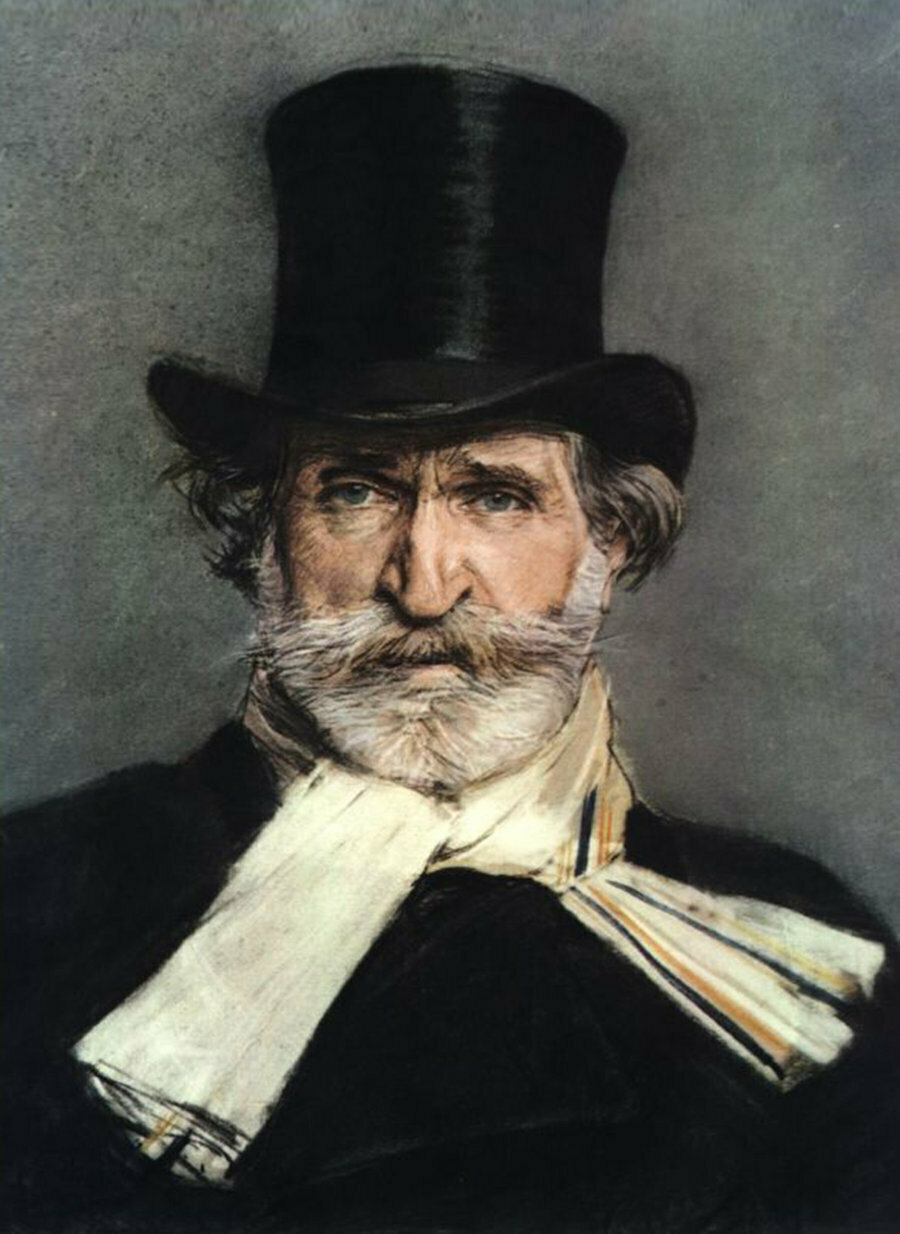

Paganini

credit: http://www.pianoparadise.com/paganini.html

No. 3 in G sharp minor, “La campanella” (1851)

In 1838, Liszt produced a second (and substantially rewritten) version as the ‘Grande Etude d’exécution transcendante d’après le Caprice de Paganini’. The title indicating that the piece was ‘after Paganini’s Caprice’ was a mistake, because, like its predecessor, it was based on the rondo theme of Paganini’s second violin concerto. In this version, the lengthy introduction leading to the main theme was replaced by three bars of bell-like rings, and many disjointed jumps and noisy low-register chromatic scales were also removed. Musically the piece had become much lighter, not least thanks to the addition of extensive, playful carnivalesque passages. The key was also changed from A minor to A-flat minor, presumably so that the big jumps would land on black keys rather than white ones, making it easier to play. It was billed as an étude, and indeed it contains some standard technical exercises such as fast repeated notes, weak fingers chromatic scales in semiquavers coupled with quaver thirds under (similar to Chopin’s Etude Op. 10 No. 2), and interlocking octaves. Generally speaking, the piece was much more interesting but not immediately awe-inspiring.

The version of ‘La Campanella’ popularly performed nowadays is the third one published in 1851 in the enharmonic G-sharp minor. Liszt was nearly 40 and had by then moved to Weimar. It is likely to have been refined and taken shape during his years as a touring virtuoso. The texture of this version is more homophonic than the two previous versions and further lightened by moving to the higher register and reducing the weight of the chords by taking notes out. The dynamic markings are also light with many passages resembling a breeze. Despite the lightened texture and reduced technical complexity, the artistry required to convey the elegance is no less demanding. It is not easy to appear effortless and at the same time to maintain the scintillating effects.

With the piece itself as a transcription-composition that underwent substantial revision, some pianists would add extra notes and their own cadenza. Busoni, for example, repeatedly played in public his own variant of the piece and eventually published his own edited version. If Liszt were still alive, he probably would not be too upset about the different interpretations of ‘La Campanella’; after all, he made the most dramatic changes himself and probably would not be playing it exactly as written in any of the versions we know.

BUSONI PLAYS Liszt LA-CAMPANELLA