Montserrat Caballé © Wikipedia

Montserrat Caballé (born 1933 and died October 6, 2018) might have been the most extraordinary of these exports. Working as an ensemble member of the decidedly second tier Basle (Switzerland) municipal theatre from 1957-1959, the Catalan soprano only broke out in 1965, when she was called on short notice to replace the indisposed Marilyn Horne at Carnegie Hall in Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia.

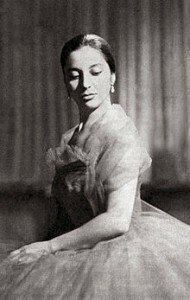

Caballé in Maria Stuarda

The young singer stunned the world with one of the most extraordinary instruments ever heard. Her distinctively full-bodied and lush voice soared or floated, thrusted or whispered, attacked or disappeared and melted away with an unmistakeably warm timbre. Her phrasing was unforgettable, though her diction remained stubbornly unintelligible. She delivered unsurpassed paper-thin pianissimi, often accompanied by an emphatic movement of her fingers as if she were gently letting the notes fly free. And she boasted an unsurpassed length of breath.

Her Preghiera, the famous prayer scene in Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda must hold the YouTube record for longest held note in this opera ever. She was also one of the fewest sopranos to fearlessly take the last two stanzas of Adriana Lecouvreur’s “Io sono l’umile ancello” in one comfortable breath (neither Callas nor Tebaldi did this). She also explored less popular roles, especially from the bel canto repertory.

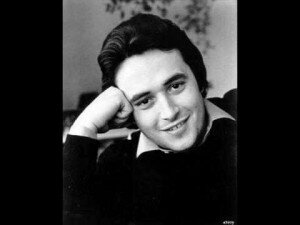

José Carreras © i.ytimg.com

Caballé and Carreras in Adriana Lecouvreur

Carreras, whose career was tragically cut short by leukemia in 1987, possessed one of the most elegant, richest and heart-wrenching voices of his generation. Not as comfortable as a victorious or triumphant hero, his timbre and temperament were that of the suffering tenor, the romantic victim, the lovelorn and doomed suitor. A voice that was impossibly sweet, dangerously vulnerable, yet powerfully assured and versatile, he delivered some of the most noteworthy verismo roles, frequently starring with Caballé. After his successful though debilitating medical treatment he returned to the stage, demonstrating not just artistic dedication but an unbending love for life.

Giacomo Aragall © operawire.com

Aragall in La Bohème

Placido Domingo, José Carreras and Luciano Pavarotti at Dodgers Stadium in Los Angeles, with conductor Zubin Mehta. © www.npr.org

Teresa Berganza © Wikipedia

Berganza sings Mozart

For three decades these – as well as other – Spanish stars stepped to the front of the line of global operatic talent. They shone, they sparkled and they gracefully stepped aside with a minimum of drama. None of them had the famously operatic hissy fits, none were known for their drama or diva antics. Though Caballé in particular had a reputation for cancelling, all were known as supportive and professional colleagues who enriched not only their times, but also cast a considerate eye on the next generation with master classes, voice competitions and an unmitigated love for the art form.

Caballé’s death at the age of 85 is the most fitting moment to reflect upon not only her astounding career, but also her enormous contribution to the grand tradition of great Spanish opera singers.

21jul1, any write up about Spanish opera singers that purposely talks around Placido Domingo, and actually leap frogs over him to others from Spain, the Land of Tenors according to Pavarotti, cannot be taken seriously. Not so much as one paragraph as is devoted to the others named, no just a token sentence fragment. This bizarre phenomenon among opera press members and opinion-havers is pathological. The fear of describing in admiring terms anything Domingo is palpable cowardice. But kudos for noticing his fellow countrymen, so there’s that…..