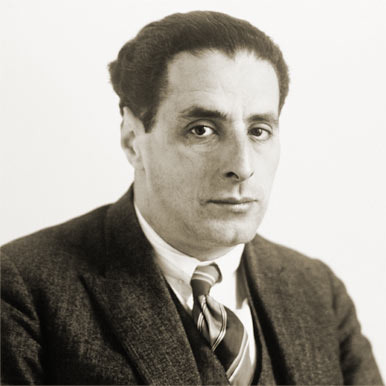

Corrected by Mozart Can you imagine one of the most astonishingly gifted musical prodigies of all times being forced to study music in secret?

Can you imagine one of the most astonishingly gifted musical prodigies of all times being forced to study music in secret?

It happened to Ernst Toch, whose father — a Jewish processed-leather dealer in Vienna — did everything possible to discourage his son’s musical interest. Under cover of darkness and bed-sheets, the six-year old Ernst taught himself the fundamentals of musical notation in a very few days. At age ten, he discovered miniature editions of ten Mozart string quartets, and “was carried away when reading the score,” he reported later. “Perhaps in order to prolong my exaltation, I started to copy it, which gave me deeper insight.” After copying five quartets, “I decided to stop at the repeat sign and try my hands at improvising the development. When I compared my efforts with the original, I felt crushed! Was I a flea, a mouse, a little nothing… but still I did not give up and continued my strange method to grope along in this way and to force Mozart to correct me.”

Toch continued to receive “instruction” from Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, but Mozart remained his idol. “If Mozart was possible,” he would sometimes declare, “then the word impossible should be eliminated from our vocabulary.” In quick succession, Toch composed his very own six string quartets, which received public performances by the renowned Rosé Quartet. He entered his Chamber Symphony in F major, composed in 1906, in an international competition for young composers and was thoroughly surprised to win the “Mozart Prize” three years later. A substantial monetary stipend attached to the prize allowed Toch to study at the Frankfurt Conservatory. He won the Mendelssohn prize for composition in 1910, and was appointed lecturer of both piano and composition at the College of Music in Mannheim in 1913. He continued to win major composition prizes, but his musical career was interrupted by having to serve the Austrian Army for 4 years on the Italian front. And as it happened across the European landscape, WW1 affected some rather severe changes.

Toch began to compose “Neue Music,” suggesting that tonality had exhausted itself and was “incapable of utterance without repeating itself. Breaking free was an inner need, as refreshing as a plunge into cold water on a tropical summer day.” His newest works scandalized audiences, and he even created the new genre of “Gesprochene Musik” (Spoken Music.) Intended as a musical joke, his Geographical Fugue for Spoken Chorus — a strict fugal canon that rigorously patterned sequences of geographical locations for spoken four-part chorus — became his most famous and influential compositions.

Toch began to compose “Neue Music,” suggesting that tonality had exhausted itself and was “incapable of utterance without repeating itself. Breaking free was an inner need, as refreshing as a plunge into cold water on a tropical summer day.” His newest works scandalized audiences, and he even created the new genre of “Gesprochene Musik” (Spoken Music.) Intended as a musical joke, his Geographical Fugue for Spoken Chorus — a strict fugal canon that rigorously patterned sequences of geographical locations for spoken four-part chorus — became his most famous and influential compositions.

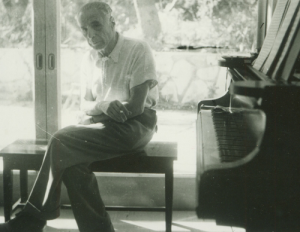

John Cage, who was in the audience at the premiere performance in 1930 remarked, “Toch was onto some good stuff back there in Berlin. And then he went and squandered it all on more string quartets!” Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 meant exile in Paris and subsequently London, where Toch started to write film music. Barely a year later he was invited to join the faculty of the New School for Social Research in New York. He also spent time in California, teaching music and philosophy at USC and composing film music for Hollywood. Toch authored a book on music theory in 1948, and from 1950, wrote seven symphonies, chamber and vocal music that return to the musical language of his youth.

Ernst Toch: Fuge aus der Geographie

More Composers

-

Pierre Rode “He moved those without understanding to mindless admiration”

Pierre Rode “He moved those without understanding to mindless admiration” -

Niccolò Jommelli “The music is beautiful, but too clever and old fashioned for the theatre”

Niccolò Jommelli “The music is beautiful, but too clever and old fashioned for the theatre” -

Arnold Schoenberg “Great art presupposes the alert mind of the educated listener”

Arnold Schoenberg “Great art presupposes the alert mind of the educated listener” -

Richard Strauss “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!”

Richard Strauss “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!”