Credit: http://www.newyorker.com/

We have long known that Ludwig van Beethoven was a man of high eccentricity. Stories about his temper became legendary, and detail sudden rages, uncontrolled emotional states, suicidal tendencies, and frequent feeling of persecution. He lived in disorderly surroundings, constantly changed his lodgings, and on occasion turned to physical violence towards friends, relative, pupils, and servants. Whether he threw hot foot at a waiter or swept the candles off the piano during a bad performance, Beethoven’s supposed insanity became common currency in Vienna. Charlotte Brunsvik wrote, “I learned yesterday that Beethoven is going crazy,” and Friedrich Zelter wrote to Wolfgang von Goethe in 1819, “Beethoven is intolerable; some say he is a lunatic.”

After the death of his brother Carl on 15 November 1815, Beethoven became embroiled in a bitter custody battle over his nephew Karl. Beethoven claimed that his sister in law Johanna was an unfit parent because she had an illegitimate child by a different father before marrying Carl, and had been convicted of theft. Although Beethoven was successful at having his nephew removed from her custody in February 1816, the case was not fully resolved until 1820. Nephew Karl, meanwhile, had been placed in a private school and trying to escape all that family animosity attempted suicide. An influential Beethoven scholar suggested, “Beethoven’s conduct in the affairs of his nephew is hardly consistent at all points with normal sanity.”

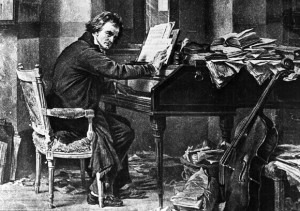

As Beethoven retreated into his inner world, he became less concerned with his outward appearance and personal hygiene. His working environment resembled a bombsite with full chamber pots stashed under the piano. A young student reports after a visit to Beethoven at Mödling: “It was four o’clock in the afternoon. As we entered we learned that in the morning both servants had gone away, and that there had been a quarrel after midnight, which had disturbed all the neighbors, because as a consequence of a long vigil both had gone to sleep and the food, which had been prepared had become unpalatable. In the living room, behind a locked door, we heard the master singing parts of the fugue of the Credo singing, howling, stamping. After we had been listening a long time to this almost awful scene … the door opened and Beethoven stood before us in his underwear with distorted features, calculated to excite fear. His first utterances were confused, as if he had been disagreeably surprised at our having overheard him. Then he remarked: ‘Pretty doings, these! Everybody has run away and I haven’t had anything to eat since yesternoon.”

Apparently, Beethoven started to ignore his grooming, pouring water over his head instead of having a good wash, and his friends had to have his dirty clothes washed while he slept. In 1820, Beethoven was staying in the resort city of Baden. He got up early one morning to go for his legendary inspirational walks. His head full of musical ideas, he walked until evening and found himself lost. Trying to find his bearings, Beethoven began peering into shops and windows, and quickly attracted the attention of the local constabulary. “I am Beethoven,” the composer proudly protested, with the constable responding, “Of course, why not! You’re a tramp; Beethoven doesn’t look like that.” So Beethoven was locked up and ordered to be kept under arrest until morning. But Beethoven would not sit quietly, as he loudly protested his incarceration. By 11pm, the commissioner had to be roused from his sleep, as Beethoven demanded to see Herzog, the music director of Wiener Neustadt to identify him. Herzog was fetched in the middle of the night, and the instant he saw the tramp exclaimed, “That is Beethoven!” Beethoven stayed in Herzog’s house for the rest of the night and was driven home by magisterial state-coach in the morning. This little episode might also have had artistic consequences. The “Scherzo” movement of Op. 110 composed around this time, sounds two folk-song quotations, “Our cat has had kittens,” and entirely apropos “I am a slob, you’re a slob!”