Britten: Owen Wingrave, Op. 85

Britten: Owen Wingrave, Op. 85

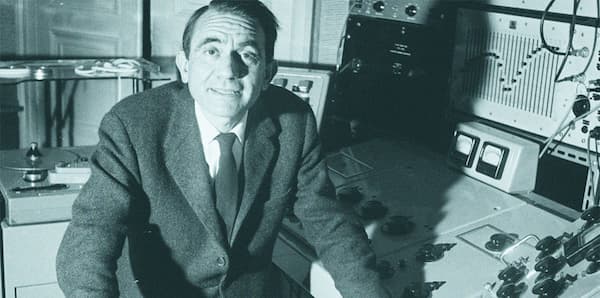

A TV opera? Yep, it happened… Back in 1971 to be precise, when Benjamin Britten wrote Owen Wingrave for the BBC. The opera was taken from TV-land and given a live revival this summer, to open the Aldeburgh Festival. I was lucky enough to be performing at the Festival with the Britten-Pears Orchestra, and as such we were part of this live adaptation of something originally intended for the small screen. Why would we bother adapting a TV show? Apart from the absence of annoying ad breaks, this opera lends itself equally well to the concert hall or living room.

The plot of the opera centres around Owen, the youngest member of the Wingrave family, who early on denounces his expected path of becoming a soldier. The rest of the opera depicts his fight with his own family as he struggles to retain this moral stance in the face of outright disbelief and anger from those who surround him.

To those familiar with Britten’s work, this plot comes as no great surprise – he was a committed pacifist, himself struggling with these beliefs from a young age. On one hand, the plot of the opera is pretty thin, what with there being only one real central story, but actually this lends itself to many moments of intensity, where one single emotion or dramatic moment is examined in searing intensity. Neil Bartlett, the director of our production, clearly saw these moments in his choice of staging when, for example, Owen sits on a simple wooden chair with his back to the audience, facing a gaping stage from which a barrage of verbal abuse from four members of his family cascades towards him.

The staging of this opera is something that is particularly tricky; moving from TV to the stage means that things that are easy with camera cutscenes become potential logistical nightmares in a theatre. We overcame this hurdle through a highly minimal set (again contributing to the intensity of the performance); a set of moveable panels that were wheeled swiftly around the stage to change the setting of the action. This panel-moving was accomplished with the help of an eight-strong cast of silent actors representing the ghosts of the Wingrave family past.

The staging of this opera is something that is particularly tricky; moving from TV to the stage means that things that are easy with camera cutscenes become potential logistical nightmares in a theatre. We overcame this hurdle through a highly minimal set (again contributing to the intensity of the performance); a set of moveable panels that were wheeled swiftly around the stage to change the setting of the action. This panel-moving was accomplished with the help of an eight-strong cast of silent actors representing the ghosts of the Wingrave family past.

Musically, the opera is incredibly wide-ranging. There are hints of Britten experimenting with serialist (12-tone) techniques, as well as flirting with bitonality and, of course, his own unique tonal language. As in the majority of post-nineteenth century operas, musical ideas and fragments are woven into the score to remind the listener of certain characters or moods. For example, Owen’s stern aunt is always preluded by fierce woodwind trills, and Owen himself has a yearning motif in a simple major key – as far removed as possible from the near-atonal outbursts that sometimes accompany his angry family members.

Our production in Aldeburgh utilised a reduction of the full score by composer David Matthews, from full orchestra to 16 players, meaning that all our parts were highly involving the whole time. A large challenge of ours was trying to give the impression of a full orchestra being present with, in reality, fewer than a quarter of the players squeezed into the modest pit at Snape Maltings. With the help of our conductor, Mark Wigglesworth, we gave it our best, and David Matthews himself commented on the richness of the sound we produced (but then again, he would say that, being the arranger and all…).

Our production in Aldeburgh utilised a reduction of the full score by composer David Matthews, from full orchestra to 16 players, meaning that all our parts were highly involving the whole time. A large challenge of ours was trying to give the impression of a full orchestra being present with, in reality, fewer than a quarter of the players squeezed into the modest pit at Snape Maltings. With the help of our conductor, Mark Wigglesworth, we gave it our best, and David Matthews himself commented on the richness of the sound we produced (but then again, he would say that, being the arranger and all…).

Thanks to the brilliant acoustic of Snape Maltings’ concert hall, the balance was often something to be wary of. Cat Cantrell, our brilliant oboe/cor anglais player, commented that while the orchestra’s parts were fun and involving, ‘I’m much much better at playing quietly now(!)’. Steuart Bedford, the conductor who premiered Britten’s final opera, Death in Venice, also attended our performance, saying he liked the addition of the harp to our ensemble. In reducing the opera, David Matthews gave the harp’s music to the piano, but not wanting to lose out on the special sonority created by Britten’s unique harp writing, Mark enlisted the help of harpist Robin Best to add the equally ghostly and percussive colours that are the harp’s speciality.

Often neglected as an over-simplified ghost story, Owen Wingrave actually has a lot to offer in terms of musical and dramatic content, and whilst perhaps it doesn’t stack up against his meatier operas such as Peter Grimes (perhaps through the sheer weight of Grimes’ reputation), Britten nonetheless creates an incredibly moving and striking piece of work, forcing you to sit up and pay attention to the themes of war, pacifism, conscientious objection and societal pressure. Not your average TV show…

More Blogs

-

The Music That Surrounds Us Discover how everyday noise became revolutionary music

The Music That Surrounds Us Discover how everyday noise became revolutionary music -

Augusta Holmès: A Composer Who Wrote Music Bigger Than Life “I must show the males what I’m made of!”

Augusta Holmès: A Composer Who Wrote Music Bigger Than Life “I must show the males what I’m made of!” -

Classical Music Unfinished and Restored IV Why did Schubert leave so many works incomplete?

Classical Music Unfinished and Restored IV Why did Schubert leave so many works incomplete? -

The Trinity of Music Deepen your understanding of music's fundamental elements here

The Trinity of Music Deepen your understanding of music's fundamental elements here