![Beethoven-04[1803]](https://interlude-cdn-blob-prod.azureedge.net/interlude-blob-storage-prod/2013/05/Beethoven-041803-263x300.jpg)

Beethoven

Piano Sonata Op. 2, No. 1

Piano Sonatas Op. 2 No. 2

Piano Sonatas Op. 2, No. 3

Historians and scholars habitually divided Beethoven’s life and work into three periods, a concept that originated with Johann Aloys Schlosser’s biography published merely months after the composer’s death. This rather simplistic construct does take into account some basic stylistic distinctions that correspond with major upheavals in Beethoven’s biography, and thereby affirm the very close relationship between the composer’s creative energies and his emotional life. However, since these divisions occur at different chronological points in different genres, the three-period framework is certainly in need of refinement. Particularly urgent is a thorough reconsideration of Beethoven’s formative musical years in the city of Bonn, where he took composition lessons from the Court Organist Christian Gottlob Neefe.

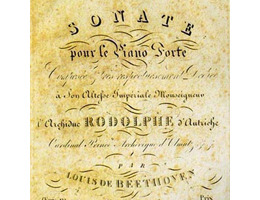

Rightfully considered the most important musical influence on the young Beethoven, Neefe soon recommended his young student to take up the assistant organist position. In support of his nomination, Neefe writes: “Louis van Beethoven, is a boy of 11 years and of the most promising talent. He plays the piano very skillfully and with power, and reads at sight very well. This youthful genius would surely become a second Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart if he were to continue as he has begun.” As is well known, Beethoven published 32 piano sonatas, beginning with his Op. 2, No. 1 in 1796. It is less well known, however, that Beethoven composed at least five additional piano sonatas, which he never published. Originating during his formative years in Bonn, these student works are essentially imitative examples of contemporary works by C.P.E. Bach, Neefe, Haydn, Mozart, Stamitz and Sterkel. Nevertheless, the young Beethoven clearly received and synthesized diverse musical practices of the time from his teacher and other composers. Although these juvenilia compositions have not received an abundance of scholarly attention — and they are certainly not performed with any kind of regularity — they nevertheless serve as a point of departure for understanding Beethoven’s entire keyboard oeuvre. Beethoven introduced himself to the city of Vienna by showcasing his talents as a pianist, and he was the first major composer in that city who did not depend on a fixed musical appointment. On one hand, he received generous allowances from his aristocratic friends and acquaintances, on the other, he was able to earn a living by taking advantage of a growing bourgeoisie interest in music and music making. Coming to terms and gaining control over the Viennese style, he composed and performed piano sonatas of extreme technical difficulty and expansive musical breath, yet also focused his energies on composing music for an infinite variety of musical ensembles and occasions.

Haydn